New year, like a newborn, starts with hope.

The next year will do the same – we will all celebrate with Auld Lang Syne and look forward to a resolution of conflicts that reared a frightening face in 2022 and 2021. Perhaps, this time, if we have learnt from history, there will not be any annihilation but only a movement towards resolution. We have more or less tackled the pandemic and are regaining health despite the setbacks and disputes. There could be more outbreaks but unlike in the past, this time we are geared for it. That a third World War did not break out despite provocation and varied opinions, makes me feel we have really learnt from history.

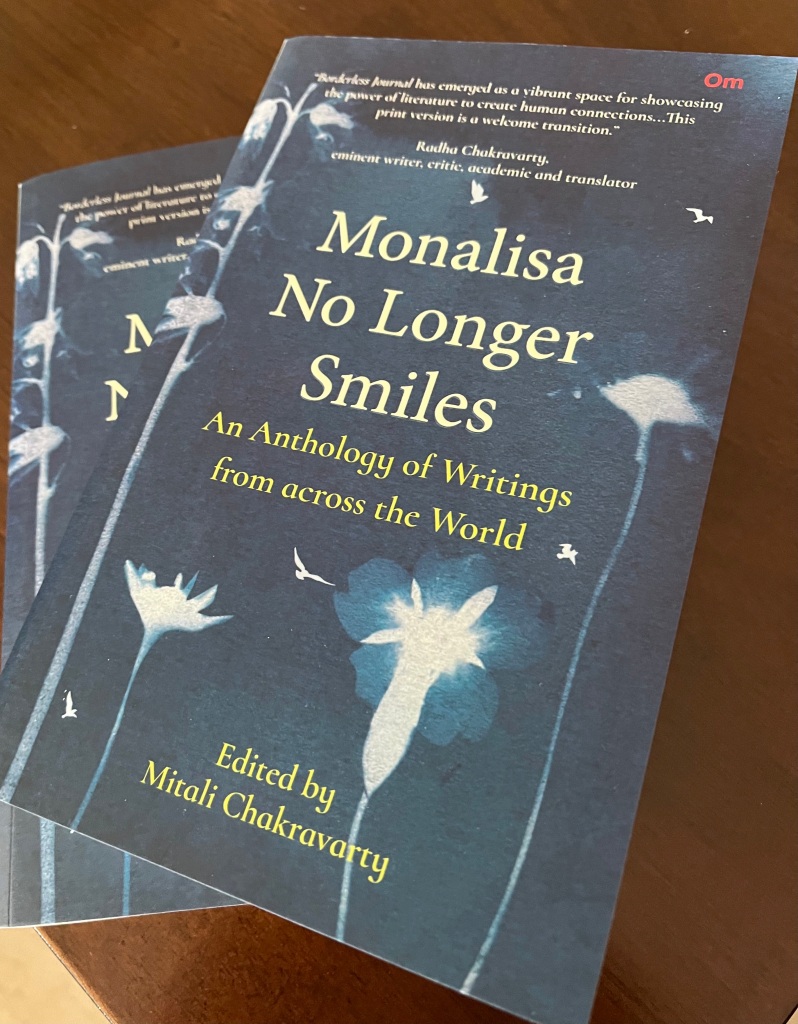

That sounds almost like the voice of hope. This year was a landmark for Borderless Journal. As an online journal, we found a footing in the hardcopy world with our own anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles: Writings from Across the World, which had a wonderful e-launch hosted by our very well-established and supportive publisher, Om Books International. And now, it is in Om Book Shops across all of India. It will soon be on Amazon International. We also look forward to more anthologies that will create a dialogue on our values through different themes and maybe, just maybe, some more will agree with the need for a world that unites in clouds of ideas to take us forward to a future filled with love, hope and tolerance.

One of the themes of our journal has been reaching out for voices that speak for people. The eminent film critic and editor, Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri , has shared a conversation with such a person, the famed Gajra Kottary, a well-known writer of Indian TV series, novels and stories. The other conversation is with Nirmal Kanti Bhattajarchee, the translator of Samaresh Bose’s In Search of a Pitcher of Nectar, a book describing the Kumbh-mela, that in 2017 was declared to be an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. Bhattacharjee tells us how the festival has grown and improved in organisation from the time the author described a stampede that concluded the festivities. Life only gets better moving forward in time, despite events that terrorise with darkness. Facing fear and overcoming it does give a great sense of achievement.

Perhaps, that is what Freny Manecksha felt when she came up with a non-fiction called Flaming Forest, Wounded Valley: Stories from Bastar and Kashmir, which has been reviewed by Rakhi Dalal. Basudhara Roy has also tuned in with a voice that struggled to be heard as she discusses Manoranjan Byapari’s How I Became a Writer: An Autobiography of a Dalit. Somdatta Mandal has reviewed The Shaping of Modern Calcutta: The Lottery Committee Years, 1817 – 1830 by Ranabir Ray Chaudhury, a book that explores how a lottery was used by the colonials to develop the city. Bhaskar Parichha has poured a healing balm on dissensions with his exploration of Rana Safvi’s In Search of the Divine: Living Histories of Sufism in India as he concludes: “Weaving together facts and popular legends, ancient histories and living traditions, this unique treatise running into more than four hundred pages examines core Sufi beliefs and uncovers why they might offer hope for the future.”

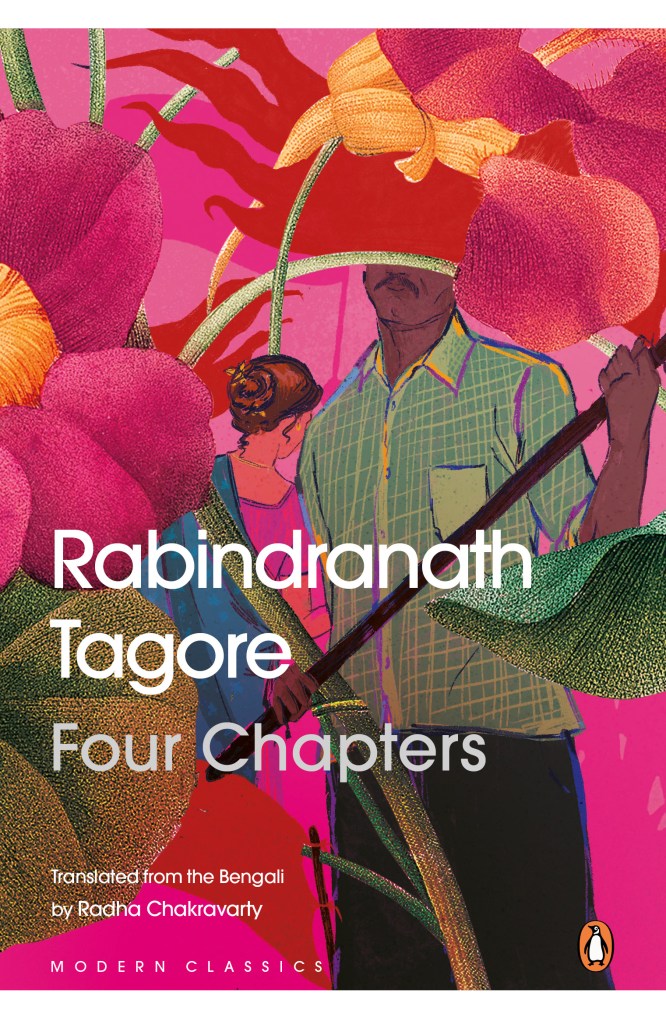

In keeping with the festive season is our book excerpt from Rhys Hughes’ funny stories in his Christmas collection, Yule Do Nicely. Radha Chakravarty who brings many greats from Bengal to Anglophone readers shared an excerpt – a discussion on love — from her translation of Tagore’s novel, Farewell Song.

Love for words becomes the subject of Paul Mirabile’s essay on James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus, where he touches on both A Portrait of the Artist as a young Man and Ulysees, a novel that completed a century this year. Love for animals, especially orangutans, colours Christina Yin’s essay on conservation efforts in Borneo while Keith Lyons finds peace and an overwhelming sense of well-being during a hike in New Zealand. Ravi Shankar takes us to the historical town of Taiping in Malaysia as Meredith Stephens shares more sailing adventures in the Southern hemisphere, where it is summer. Saeed Ibrahim instils the seasonal goodwill with native Indian lores from Canada and Suzanne Kamata tells us how the Japanese usher in the New Year with a semi-humorous undertone.

Humour in non-fiction is brought in by Devraj Singh Kalsi’s ‘Of Mice and Men’ and in poetry by Santosh Bakaya. Laughter is stretched further by the inimitable Rhys Hughes in his poetry and column, where he reflects on his experiences in India and Wales. We have exquisite poetry by Jared Carter, Sukrita Paul Kumar, Asad Latif, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal, Michael R Burch, Sutputra Radheye, George Freek, Jonathan Chan and many more. Short stories by Lakshmi Kannan, Devraj Singh Kalsi, Tulip Chowdhury and Sushma R Doshi lace narratives with love, humour and a wry look at life as it is. The most amazing story comes from Kajal who pours out the story of her own battle in ‘Vikalangta or Disability‘ in Pandies’ Corner, translated from Hindustani by Janees.

Also touching and yet almost embracing the school of Absurd is PF Mathew’s story, ‘Mercy‘, translated from Malayalam by Ram Anantharaman. Fazal Baloch has brought us a Balochi folktale and Ihlwha Choi has translated his own poem from Korean to English. One of Tagore’s last poems, Prothom Diner Shurjo, translated as ‘The Sun on the First Day’ is short but philosophical and gives us a glimpse into his inner world. Professor Fakrul Alam shares with us the lyrics of a Nazrul song which is deeply spiritual by translating it into English from Bengali.

A huge thanks to all our contributors and readers, to the fabulous Borderless team without who the journal would be lost. Sohana Manzoor’s wonderful artwork continues to capture the mood of the season. Thanks to Sybil Pretious for her lovely painting. Please pause by our contents’ page to find what has not been covered in this note.

We wish you all a wonderful festive season.

Season’s Greetings from all of us at Borderless Journal.

Cheers!

Mitali Chakravarty

.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles