Keith Lyons in conversation with Ivy Ngeow, author and editor of a recent anthology of Asian writing

Ivy Ngeow has interesting perspectives on writing which would resonate with many. She started writing at a young age. With a novel in circulation, this is her first attempt to create an anthology which would unite writers and the English language variously interpreted. She has collected stories with a variety of dialects in English, retaining the differences with each telling. Her editorial experiment is unusual. She tells us, “The Asian words in the anthology are similarly seamless threads sewn into the prose. It would be oppressive to correct the patois and italicise words which are not even foreign to the characters and the narrative. Instead, they are made part of the author’s tongue and means of communication. It is how I’d develop writers writing in English.” And she is bold enough to admit, “Anyway, all writers are outsiders. That is why we write.” Keith Lyons had a candid and interesting conversation with her.

What’s your background, and writing career?

I have an MA in Writing from Middlesex University and my first novel, which won the International Proverse Prize, was published in 2017. I have been in the industry of architecture and interior design for almost 30 years, but I have been writing since I could hold a pencil. I’ve always had that sense of a writing urge which came and went depending on what I was going in my life at the time. I always wrote, whenever I could, on the plane, in hotel rooms, at home in bed. From the time I won my first commendation as a teenager in a Straits Times national competition, I felt that writing was something real, and not imaginary.

Where is home for you, how do you identify, and where’s home for you now?

I live in London. Most of the time I identify as a regular working suburban Asian mum. The long days and short-term challenges I face are just like any other family woman’s.

How did you get the idea for producing an anthology of Asian writing?

The idea was to welcome more books which I loved to read but felt were lacking: beautiful, diverse and eclectic books by the culturally underrepresented. These are the kinds of books that I was raised with — international stories with imaginative storytelling on multiple themes such as the diaspora, culture and identity, and not even necessarily Asian. It is in our collective interest, as readers and writers, to hear more diverse voices.

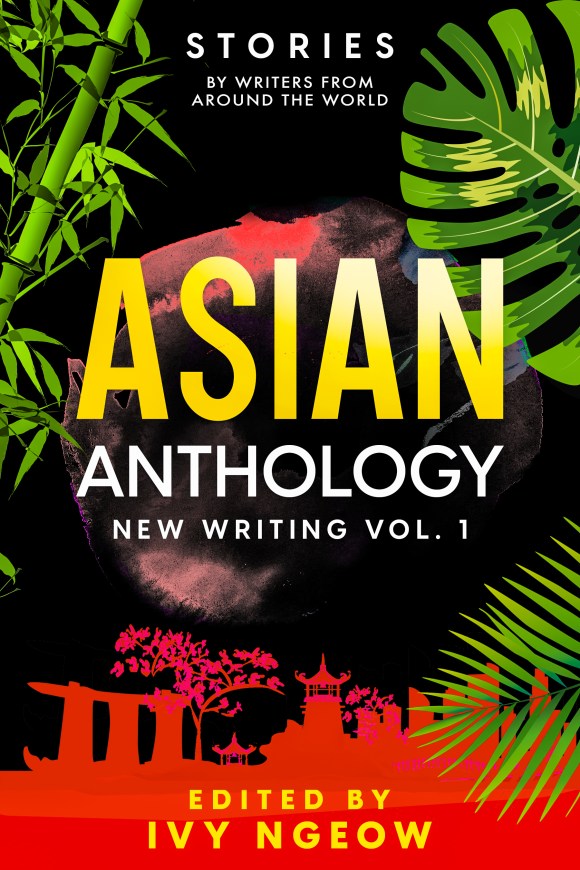

What was the process for seeking submissions and then selecting the featured stories for Asian Anthology: New Writing Vol. 1: Stories by Writers from Around the World?

I put out a call for submissions in October with a closing date in December. We received more than a hundred entries. Apart from the requirement for the writing to be set in Asia, writers of any nationality or gender were eligible to submit for this publication, in keeping with Leopard Print’s inclusion and diversity policy. The contributors in this book have come from Malaysia, Singapore, India, Myanmar, Hong Kong, Serbia, Austria, France, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. Although it was my first attempt at doing selection and curation, I could tell the strength of the piece from the first line or first paragraph. This is a good tip for writers. Nail that first line, then sculpt that first paragraph, so that the hook is sharp.

So was this the first time you’ve done something like this, or have you had experience in editing and publishing?

This was my first time doing a large-ish body of work. I have written and edited single stories and non-fiction pieces, newsletters, articles, blogs etc.

What’s been the response from the authors featured in the first volume?

The authors are thrilled to have a book out in the UK. They understand that getting a book out means endorsement by their readership and by the editorial team. They also appreciate that they will be receiving a share of royalties.

How do you think the book explores issues of culture and conflict, as well as insider and outsider views?

The cultural insights and conflicts are depicted through the exploration of ideas and storytelling. Only through stories and characterisation do we make sense of reality. Through the microcosms of scenarios, the viewpoints of characters are at the heart of emotional conflict and tension, whether or not it’s viewed by an outsider. Anyway, all writers are outsiders. That is why we write.

Tell us about why you decided to have a reasonably hands-off editorial stance, allowing both American and UK English, as well as use of local non-English words?

It’s hands-on, not hands off, as I feel I assimilated worlds within those literary worlds. Each story required editorial decision based on the cultural stance of the author. The language they have written in reflects their education, their origins and their own decisions. It would have been wrong to choose one English over another. The “Englishes”, colloquialism and vernacular are a reflection of our times and the modern movement. During my MA in Writing, my subject matter was patois and post-colonial literature. I have a whole story written in dialect which won the Middlesex University Literary Prize. Middlesex made me the writer that I am, because I learned that foreign is actually a very loose and relative term. What is foreign to someone is not foreign to another. The true English language is an assimilative one. It is Saxon, French and German. Later it has Portuguese, Indian, Chinese and Malay words too. Where the British sailed through, words sailed through. Are kowtow, verandah, bungalow, croissant and spaghetti still foreign? At which point did they become non-italicised? The Asian words in the anthology are similarly seamless threads sewn into the prose. It would be oppressive to correct the patois and italicise words which are not even foreign to the characters and the narrative. Instead, they are made part of the author’s tongue and means of communication. It is how I’d develop writers writing in English.

One story appears in both Malay and with its English translation – why did you decide to do that?

Most readers in Asia are bilingual if not trilingual. I feel that for the intended audience, there would be scope for a bilingual story because it is one that is about a young Muslim girl’s glimpse of her oppressors. Her language was fluid and poetic, bleeding into the English translation naturally.

One of the themes throughout the book is the conflict over tradition and duty to family, do you think this is more evident throughout Asia as it modernises and opens up?

I think so. Family and tradition create natural tension and conflict in any form of literature. Part of introducing this anthology is that Asia is modern. But. It is a modern that holds onto a traditional world that is in part dying, like dialects, foods of poverty, too much or too little education, breakdown of families. These will always be the recurrent themes in modern Asian literature.

Do you think the first volume achieved its aim to showcase new and established writers from across Asia as well as non-Asians writing about Asia?

Some have never been published or have not written for ten years. Some are published and/or award-winning. We are giving them this platform and opportunity. Reading and writing is a community, a two-way street. By giving writers online and in-person presence to raise their profiles, and readers a channel through which they not only discover and read, they can also hear, see and watch the authors.

The connection is further strengthened by organising online events, real “live” performance readings and book-signings by four of the authors in London, and distribution in real physical bookshops like Daunt in the UK and Silverfish Books in KL, and online print distribution on Waterstones, Barnes and Noble, Amazon, and online digital distribution on Scribd, Googleplay Apple Books, Barnes and Noble Nook, Kobo and Apple Books.

Social media posts which increase visibility for the authors and their audience engagement. More engagement will encourage the writers to write more and secure the notion that we as readers and writers, are not alone.

These ways of connections and relationships are long term. Our mission was to showcase and be showcased and we have done that.

What’s reception to the book been so far, with it only just appearing in hard copy and available in Malaysia and soon the UK?

From the Goodreads reviews, it has been well-received. It is unique in the sense that the strong original voices and the different “Englishes” of the writers have been retained, with foreign words not italicised. It is a true reflection of society and of our cultural diversity. The paperback version sold out within a weekend at Silverfish Books, Kuala Lumpur. Now it is on its second print run. Print copies are now available worldwide in both paperback and in ebook versions.

Do you have any plans to produce more volumes, and if so, when will you open submissions?

We will look at the profits and losses, whether it would be viable, but it is likely that we will go ahead with Vol. 2 despite global uncertainties and crises. In autumn we may put out the call for submissions for release in spring. We are also considering focusing on fiction only for Vol. 2 to further “niche down”. (I made that up but I hope it is a verb.) However, we know the economic challenges are vast. With the world only just recovering from the blight of 2020-21, now we are also seeing the consequences of the war in Europe, with purse strings being tightened. As readers and writers, we are conflicted by these factors, because more than ever, people need stories. Stories of escape, frustration, humour, darkness, love, hope. All stories are about our humanity.

Click here to read the book excerpt.

Click here to read the review.

Keith Lyons (keithlyons.net) is an award-winning writer, author and creative writing mentor, who gave up learning to play bagpipes in a Scottish pipe band to focus on after-dark tabs of dark chocolate, early morning slow-lane swimming, and the perfect cup of masala chai tea. Find him@KeithLyonsNZ or blogging at Wandering in the World (http://wanderingintheworld.com).

Click here to read an excerpt from the anthology.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL