The sky weeps blood, the earth cannot contain

The sorrow of the young ones we've slain.

How now do dead kids laugh while stricken by red rain?

— from Stricken by Red Rain: Poems by Jim Bellamy

When there is war

And peace is gone

Where is their home?

Where do they belong?

— from Poems on Migrants by Kajoli Krishnan

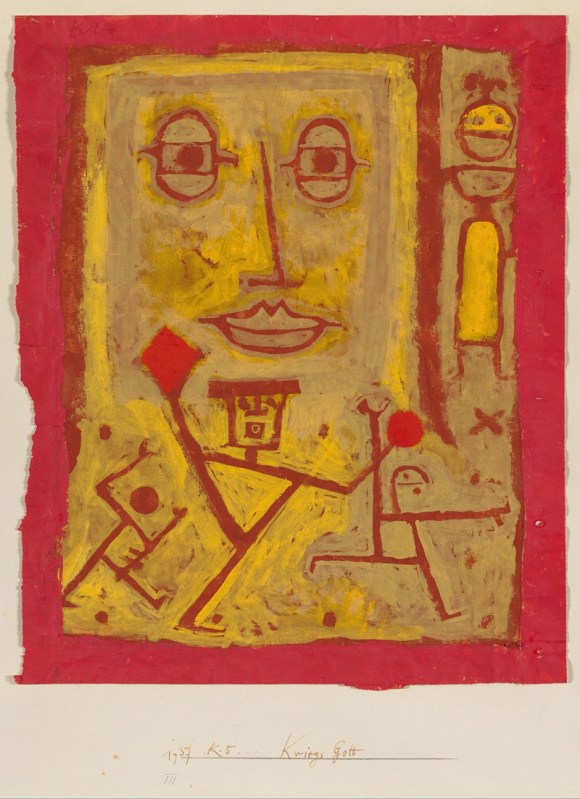

Poetry, prose — all art forms — gather our emotions into concentrates that distil perhaps the finest in human emotions. They touch hearts across borders and gather us all with the commonality of feelings. We no longer care for borders drawn by divisive human constructs but find ourselves connecting despite distances. Strangers or enemies can feel the same emotions. Enemies are mostly created to guard walls made by those who want to keep us in boxes, making it easier to manage the masses. It is from these mass of civilians that soldiers are drawn, and from the same crowds, we can find the victims who die in bomb blasts. And yet, we — the masses — fight. For whom, for what and why? A hundred or more years ago, we had poets writing against wars and violence…they still do. Have we learnt nothing from the past, nothing from history — except to repeat ourselves in cycles? By now, war should have become redundant and deadly weapons out of date artefacts instead of threats that are still used to annihilate cities, humans, homes and ravage the Earth. Our major concerns should have evolved to working on social equity, peace, human welfare and climate change.

One of the people who had expressed deep concern for social equity and peace through his films and writings was Satyajit Ray. This issue has an essay that reflects how he used art to concretise his ideas by Dolly Narang, a gallery owner who brought Ray’s handiworks to limelight. The essay includes the maestro’s note in which he admits he considered himself a filmmaker and a writer but never an artist. But Ray had even invented typefaces! Artist Paritosh Sen’s introduction to Ray’s art has been included to add to the impact of Narang’s essay. Another person who consolidates photography and films to do pathbreaking work and tell stories on compelling issues like climate change and helping the differently-abled is Vijay S Jodha. Ratnottama Sengupta has interviewed this upcoming artiste.

Reflecting the themes of welfare and conflict, Prithvijeet Sinha’s essay takes us to a monument in Lucknow that had been built for love but fell victim to war. Some conflicts are personal like the ones of Odbayar Dorj who finds acceptance not in her hometown in Mongolia but in the city, she calls home now. Jun A. Alindogan from Manila explores social media in action whereas Eshana Sarah Singh takes us to her home in Jakarta to celebrate the Chinese New Year! Farouk Gulsara looks into the likely impact of genetic engineering in a world already ripped by violence and Devraj Singh Kalsi muses on his source of inspiration, his writing desk. Meredith Stephens tells the touching story of a mother’s concern for her child in Australia and Suzanne Kamata exhibits the same concern as she travels to Happy Village in Japan to meet her differently-abled daughter and her friends.

As these real-life narratives weave commonalities of human emotions, so do fictive stories. Some reflect the need for change. Fiona Sinclair writes a layered story set in London on how lived experiences define differences in human perspectives while Parnika Shirwaikar explores the need to learn to accept changes set in her part of the universe. Spandan Upadhyay explores the spirit of the city of Kolkata as a migrant with a focus on social equity. Both Paul Mirabile and Naramsetti Umamaheswararao write stories around childhood, one set in Europe and the other in Asia.

As prose weaves humanity together, so does poetry. We have poems from Jim Bellamy and Kajoli Krishnan both reflecting the impact of war and senseless violence on common humanity. Ryan Quinn Flanagan introduces us to Canadian bears in his poetry while Snigdha Agrawal makes us laugh with her lines about dogs and hatching Easter eggs! We have a wide range of poems from Snehprava Das, George Freek, Niranjan Aditya, Christine Belandres, Ajeeti S, Ron Pickett, Stuart McFarlane, Arthur Neong and Elizabeth Anne Pereira. Rhys Hughes concludes his series of photo poems with the one in this issue — especially showcasing how far a vivid imagination can twist reality with a British postman ‘carrying’ sweets from India! His column, laced with humour too, showcases in verse Lafcadio Hearn, a bridge between the East and West from more than a hundred years ago, a man who was born in Greece, worked in America and moved to Japan to even adopt a Japanese name.

Just as Hearn bridged cultures, translations help us discover how similarly all of us think despite distances in time and space. Radha Chakravarty’s translation of Kazi Nazrul Islam’s concerns about climate change and melting icecaps does just that! Professor Fakrul Alam’s translation of Nazrul’s lyrics from Bengali on women and on the commonality of human faith also make us wonder if ideas froze despite time moving on. Tagore’s poem titled Asha (hope) tends to make us introspect on the very idea of hope – just as we do now. At a more personal level, a contemporary poem reflecting on the concept of identity by Munir Momin has been translated from Balochi by Fazal Baloch. From Korean, Ihlwah Choi translates his own poem about losing the self in a crowd. We start a new column on translated Odia poetry from this month. The first one features the exquisite poetry of Bipin Nayak translated by Snehprava Das. Huge thanks to Bhaskar Parichha for bringing this whole project to fruition.

Parichha has also drawn bridges in reviews by bringing to us the memoirs of a man of mixed heritage, A Stranger in Three Worlds: The Memoirs of Aubrey Menen. Andreas Giesbert from Germany has reviewed Rhys Hughes’ The Devil’s Halo and Somdatta Mandal has discussed Arundhathi Nath’s translation, The Phantom’s Howl: Classic Tales of Ghosts and Hauntings from Bengal. Our book excerpts this time feature Devabrata Das’s One More Story About Climbing a Hill: Stories from Assam, translated by multiple translators from Assamese and Ryan Quinn Flangan’s new book, Ghosting My Way into the Afterlife, definitely poems worth mulling over with a toss of humour.

Do pause by our contents page for this issue and enjoy the reads. We are ever grateful to our ever-growing evergreen readership some of whom have started sharing their fabulous narratives with us. Thanks to all our readers and contributors. Huge thanks to our wonderful team without whose efforts we could not have curated such valuable content and thanks specially to Sohana Manzoor for her art. Thank you all for making a whiff of an idea a reality!

Let’s hope for peace, love and sanity!

Best wishes,

Mitali Chakravarty

Click here to access the contents page for the May 2025 Issue

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.