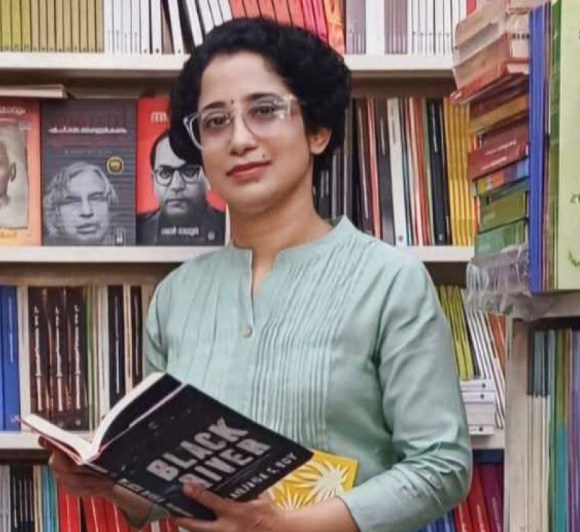

By Hema R

She restores textiles at the museum in Central Chennai. Her fingers work over ancient threads as if decoding messages from the dead. This is a job that requires patience, belief in the value of preservation and a certain kind of loneliness.

Every day she lets the early morning sunlight into her apartment, 308, which has walls the colour of abandoned hope.

Her grandmother named her Yazhini. “It originates from the name of a stringed instrument in Tamil,” she had explained to the young girl. A stringed instrument, a hollow vessel, designed to resonate with whatever touches it. To amplify what might otherwise go unheard. Yazhini has spent thirty-two years resisting resonance. She has built her life in measures: the precise fold of conservation tissue; the exact temperature of her morning filter coffee; the calculated distance she maintains from her neighbours and from herself.

She first noticed her shadow move on a Wednesday. It lingered on the wall after she had stepped away, like an afterthought or a question. Yazhini noticed and catalogued the anomaly in her mind under “phenomena: unexplained” and continued washing dishes.

But the shadows continue to persist in their small rebellions. They stretch toward one another when she isn’t looking directly at them. They pulse slightly, as if breathing. Waiting.

She watches her grandmother’s lacquered trunk, brought from their ancestral house after the funeral. For three years it has served as an oversized paperweight, holding down memories she has no interest in excavating. The trunk is red-black, the colour of dried blood, with brass fittings gone green at the edges. Sometimes, in the thin light between sleeping and waking, Yazhini imagines it breathes in time with the shadows.

On the night of the new moon, Yazhini returns home damp with rain. The power is out. She lights a candle, and in its uncertain illumination, the shadow cast by her hand seems to drift away from her fingertips.

Without thinking she reaches toward the disloyal shadow and brushes against it. Immediately it feels cool like silk underwater, substantial as regret. Her shadow peels away, a layer of herself she didn’t know could be removed.

She holds it cupped in her palms. It doesn’t weigh anything, but it carries something. Memory, perhaps.

The trunk seems the logical place for it. When she lifts the heavy lid, the interior smells of camphor, cloves, and memories. Her shadow slides from her hands to the bottom of the trunk, spreading and settling as if it has found its home.

This doesn’t frighten her. Instead, she feels the first vibration of a string, long silent inside her. An unheard note being played.

The trunk closes with a sound like satisfaction.

In the days that follow, Yazhini discovers what it is to be a collector of absences. Other shadows reach for her now. The barista’s shadow stretches across the counter, elongating itself unnaturally. The museum director’s shadow pools at her feet during budget meetings.

The shadows know. They have been waiting for someone hollow like her who’s sensitive enough to hold them.

She learns that permission matters. A shadow freely given slides easily into her hands, cool and weightless. A shadow taken leaves a residue like ash on her fingertips.

Mr. Renganathan from apartment 110, a man, eighty-seven years old, who feeds pigeons on the rooftop with the devotion of the religious, is the first to offer his shadow directly to Yazhini. “Take it,” he says, not looking at her but at the sky beyond the building’s edge. “It’s tired of following me.” His shadow has worn thin in places, gossamer with age, and the edges fraying like old silk. When it detaches from his feet, there is a sound like a sigh of relief.

That night, with Mr. Renganathan’s shadow nestled among the others in the trunk, Yazhini dreams of the flood. Not the sanitized version from newspaper archives, but the visceral experience of it: the roar of rising waters, the weight of sodden belongings hastily gathered, the sight of familiar streets transformed into rushing rivers. She wakes tasting salt, uncertain if the tears are hers or that of the memories’ from the shadow. The trunk is open a crack. A thin seam of darkness spills onto her bedroom floor.

Inside, the shadows are not still. They dance, or perhaps they struggle. Yazhini watches until dawn.

In the morning, she examines herself in the mirror. There is no visible difference. Her body casts a shadow. Weaker, perhaps, diluted like the tea she makes some evenings; steeped too briefly, but present nonetheless.

She has not become a vampire or a ghost, those staples of stories where the self is compromised. Yet something has changed. The stringed instrument of her name now plays notes she cannot control. She feels the absence of her original shadow like an amputee might sense a phantom limb, present in its nonexistence.

At the museum, she works on a fragment of brocade retrieved from a shipwreck. Three hundred years underwater, and still some threads hold their colour. Preservation is an act of defiance against time. Or perhaps an accommodation with it or a negotiation. As she works, she becomes aware of the shadows cast by ancient fabrics, the negative spaces between threads that have outlived their creators. These shadows too seem to recognize her. They lean toward her hands as she passes over them with her tools. She learns that history casts its own kind of shadow. She wonders what these textile shadows would feel like if she were to collect them. What medieval fingers might have left behind, what Renaissance whispers might still cling to the weave? She restrains herself. There are boundaries, even in the unprecedented.

That evening, she visits Mr. Renganathan on the rooftop. He sits with the pigeons arranged around him like attendants. His frail body is wrapped in a cardigan despite the Chennai heat. Without his shadow, he seems more substantial. Unburdened.

“You saw?” he asks, not specifying what. Yazhini nods.

“Madurai, 1993,” he continues. “When the floods came. I was 55 then, with my clockmaker’s shop well-established for over two decades. The waters rose so quickly.” His voice softens. “I carried my mother on my back through waist-deep water. My wife Lakshmi held our daughter’s hand, clutching our family documents in a waterproof pouch around her neck. We lost the shop, all my precision tools, everything we’d built. But we survived.” He tells her about rebuilding the clockmaker’s shop where he worked for the next fifteen years, the precision of gears and springs, the satisfaction of fixing what is broken; his wife Lakshmi, who died remembering the garden of her childhood home that she never saw again. As he speaks, Yazhini notices that a new shadow has begun to form beneath him, faint as a watermark. Shadows regenerate, apparently. The body forgives.

The shadows in her trunk multiply. Each night, they perform for her, or perhaps for themselves. Shadow theatre without the puppeteer. They blend and separate, forming patterns that remind her of the textiles she restores: mandalas, paisleys, intricate borders that tell stories in a language she almost understands. Sometimes she sees faces in the patterns, sometimes entire scenes: a child running through monsoon puddles; lovers meeting beneath a banyan tree; an old woman teaching a girl to play the Yazh, an instrument that resembles the harp. Their fingers move in unison across phantom strings. Yazhini begins to understand that she is not collecting shadows but stories, not capturing darkness but light impressed upon it. Memory, it turns out, has texture and weight, density and dimension. It can be archived like fabric, preserved against the ravages of forgetfulness.

As weeks pass, Yazhini decides to take only what is freely offered, and even then, she is selective. Some burdens are not hers to carry.

Mr. Renganathan’s health deteriorates. His visits to the rooftop become less frequent, then cease altogether. Yazhini visits him in apartment 110. His new shadow, still forming, has a different quality than the one she keeps. Cleaner somehow. Unburdened by memories, his body has learned to grow only what it can bear.

“I have a daughter,” he tells her on a Thursday morning when his breath catches between words.

“In Toronto. We haven’t spoken in eleven years.” He doesn’t explain why.

That evening, Yazhini brings a portion of his original shadow to him, the part that holds his daughter at age seven, spinning in a light blue dress. He cups it in papery hands, and for a moment his eyes focus on something beyond the walls of apartment 110.

She helps him record messages. Not the formal apologies of deathbed reconciliations, but everyday words: descriptions of pigeons on the rooftop, complaints about the building manager’s music, recipe of his wife’s biryani. The shadows know what needs to be said when words alone are insufficient.

One morning, “Twilight Towers” absorbs another absence, the way buildings do.

After the funeral, Yazhini finds Mudra, the daughter from Toronto, standing in the hallway outside apartment 110. She wears her grief awkwardly, like borrowed clothing.

“He left me a key,” she says, “and instructions to meet someone named Yazhini.” The resemblance to her father is not in her features but in the quality of her shadow, which stretches toward Yazhini of its own accord.

Back in apartment 308, the trunk waits. When Yazhini opens it, the shadows perform not their usual abstract patterns but a specific scene: a man teaching a little girl to repair a clock. Precise and tender movements. Mudra watches without speaking, her hand at her throat where a locket might hang if she were the type of woman who wore her memories visibly.

“What is this?” she finally asks.

“A type of conservation,” Yazhini answers.

That night, after Mudra returns to her hotel with a promise to visit again tomorrow, Yazhini sits with the open trunk. The shadows have settled into a new configuration. Among them, she notices something unexpected: a small patch of darkness the size of a thumbprint, containing no memory but rather the impression of potential. Not a shadow of what was, but of what might be. A beginning rather than an archive.

The seasons shift. Mudra extends her stay. She finds an apartment in Chennai city, ostensibly to settle her father’s affairs but really to settle something within herself. She visits Yazhini often. They drink coffee. They feed pigeons. Occasionally, they examine shadows together.

The trunk accommodates its growing collection, expanding inward in defiance of spatial logic. The shadows develop rhythms, preferences. Some cling to each other, forming composite memories that never existed but feel true nonetheless. Others maintain their integrity, reluctant to blend. All of them, Yazhini notices, seem to pulse in time with her heartbeat.

One morning Yazhini arrives at the museum to find her supervisor agitated. A rare textile has arrived. A fragment of silk believed to belong to an unnamed Tamil musician from the colonial era. “It needs your touch,” he says, which is as close to praise. The fabric, when Yazhini, unwraps it, carries a pattern she recognises instantly. It had the same configuration the shadows formed in her trunk the previous night.

She works with careful precision. As she does, she becomes aware of her own shadow on the workbench. She wonders how it has changed in these months of keeping others’ darkness. It carries subtle patterns now, impressions from all the shadows she’s collected. The outlines of her fingers contain multitudes: Mr. Renganathan’s clockmaker precision, the barista’s musical rhythm, the museum director’s careful assessment, and countless others.

In her apartment that evening, Yazhini sits before her grandmother’s trunk. “Is this what you meant me to find?” she asks the empty room. No answer comes, but she doesn’t expect one. The dead cast no shadows. They become them.

She opens the trunk and watches the shadows dance. In certain slants of light, she can see them extending beyond the trunk’s confines, threading invisibly throughout the building and beyond, connecting residents who may never speak to one another directly. Mr. Renganathan’s clockmaker hands. Mudra’s cautious smile. The barista’s fluid movements. The child who skips instead of walking.

Yazhini remembers her grandmother’s words about her name. That it meant not just any stringed instrument, but specifically one that requires both hands to play: one to create the note, one to shape it. One to preserve, one to transform. One to hold the past, one to invite the future.

She has become a keeper of shadows, yes, but more importantly, a keeper of the light that made them possible.

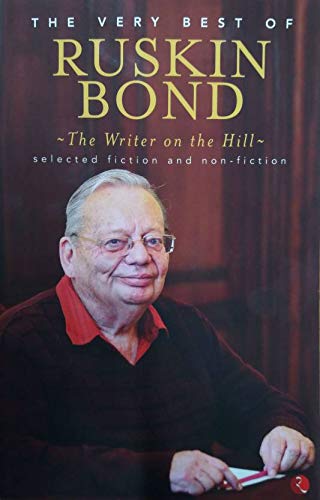

Hema R is a novelist, children’s author, and poet. Her short story is featured in Ruskin Bond’s “Writing for Love” anthology.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International