Ratnottama Sengupta travels through time and space to explore a UNESCO-declared ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity‘, a festival called, Durga Puja

It was Saptami, the second day of the five-day Durga Puja that had been inaugurated the previous day. I had new dresses lined up for all five days. But the dawn of Saptami brought us news of disaster. A short circuit had razed the entire pavilion along with the clay icons of Durga, her brood comprising Ganesh, Kartik, Lakshmi, Saraswati and their vahanas — the lion, owl, swan peacock and mouse. Gone was the chaalchitra, the halo-like backdrop presided over by Lord Shiva and depicting the story of the goddess who fought the demons Chanda Munda, Shumbha, Nishumbha, Madhu Kaitav, Raktabeej Mahishasur…

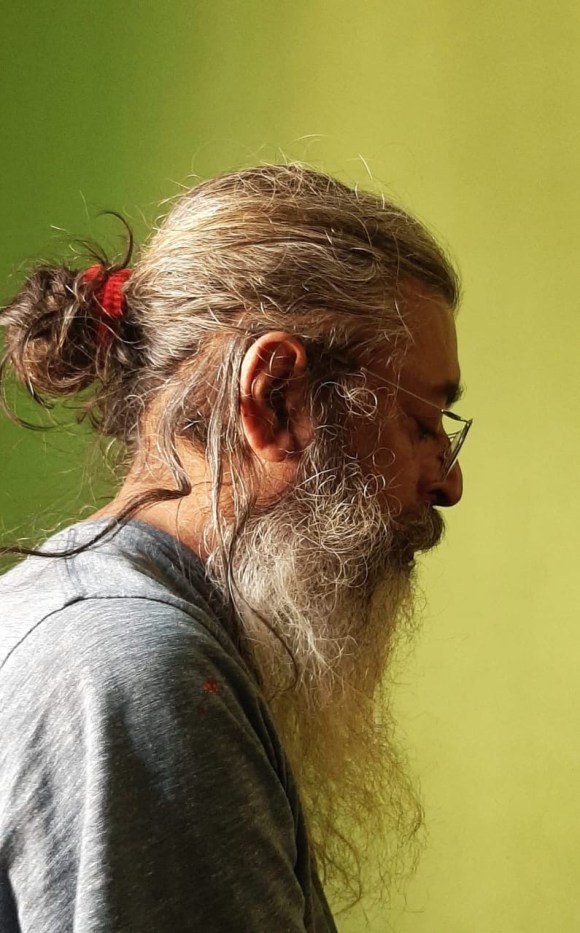

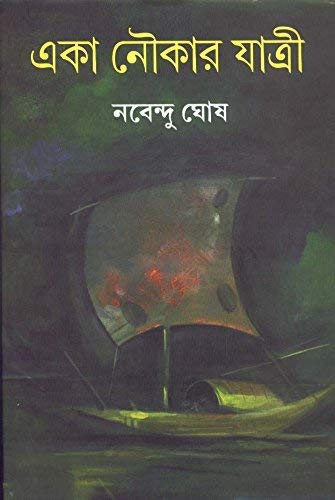

We were mourning all through the Pujas that particular year. No new dresses worn, no new shoes on our feet, no ‘Dussehra Greetings’ nor any sweets on ‘Bijoya’. We felt sad not because of the effort my father, Nabendu Ghosh, had put in as the President of the Puja conducted by the Udayan Club, but because of the belief that “Durga comes home to her parents during this period.”

*

My father’s ancestral home was in East Bengal. My grandfather, Nabadwip Chandra Ghosh, was an Advocate who relocated to Patna in 1920. Every autumn after that the family would travel back to Dhaka for a month. Because the Durga Puja in their family home was the lone puja of Kalatiya, the village which is now a suburb of Dhaka. Everyone there would flock to ‘Ukil Babur Bari’[1]for the puja and prasad in the afternoon and the cultural programmes in the evening. Jatra, theatre, Pala Gaan, Naam Sankirtan — the itinerant groups of performers comprised of singers, actors, the narrator or the sutradhar, and the adhikari or the manager. It was at one such performance that Baba[2], then all of seven, fell in love with a ‘lady’ who had played Draupadi. Imagine his disappointment when the departing ‘lady’ turned out to be a clean shaven youth!

The next year at that very Puja Mukul [3]— the pet name of Nabendu Bhushan — first ‘acted’ as a Sakhi[4]! At eight his ‘manhood was offended at the thought of playing a handmaiden. But when he stood on the stage with three other boys, all dressed in finery and wigs, all praying ‘Madhav rakho charaney[5]!’ he was transported to Lord Krisha’s court in ancient Dwarka. That was his first experience of Rasa[6] — and unaware even to himself he had set on a lifetime’s journey with the arts.

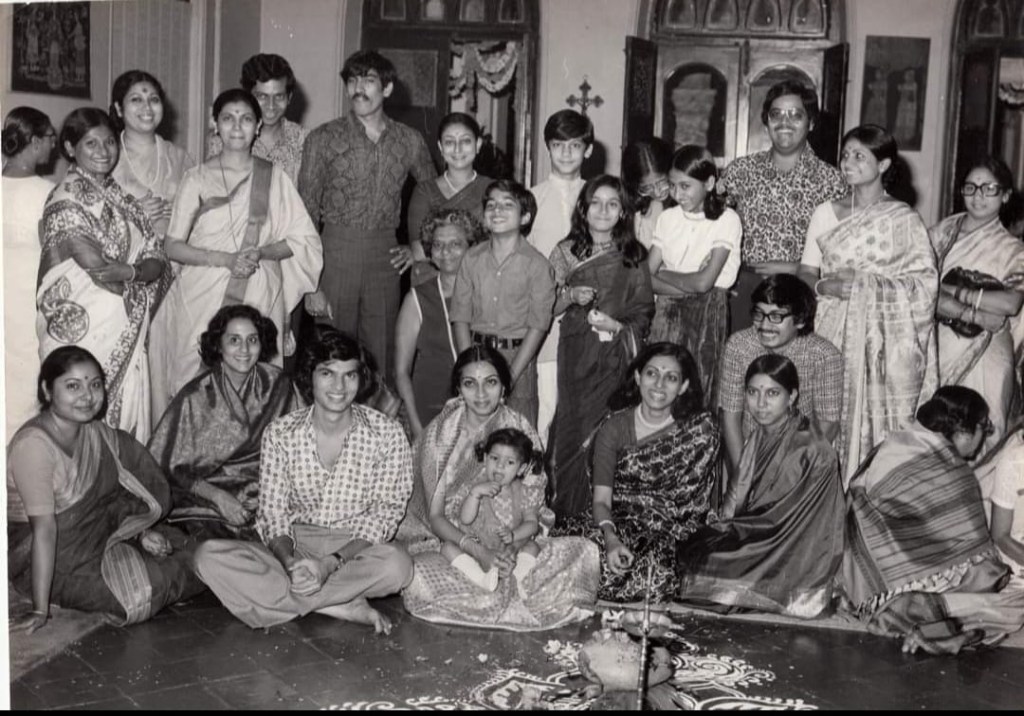

When life took him to Bombay in 1951, there were few Pujas and no possibility of publishing anything in Bengali. Pragati Club of Andheri started a Puja in Mohan Studios that had Bimal Roy as the President and Nabendu Ghosh as the Secretary. That Puja continues to this day — and to this day these two names figure in the brochure the club publishes annually. Pragati[7] used to bring out a handwritten magazine back then. PraBas — meaning, migrant life, was an acronym for Prabasi Bangla Samaj.[8] Edited by Nabendu Ghosh, it boasted hand-painted covers by renowned artist Chitto Prasad.

Pragati, Kallol, Udayan, Natun Palli, Shivaji Park, Chembur — all the major Pujas of Mumbai continue to publish a brochure for the Pujas as a souvenir of the festival and also to raise funds through ads by the sponsors.

*

All through my school life, which I spent travelling to the Bengali Education Society’s English High School at Dadar, I would necessarily spend one evening rolling into late night at the Shivaji Park puja pandal. Long in advance I would plan which dress to wear. The latest Bengali movie would be screened. The Puja Specials would have already come home — in the pavilion we would pick up some new publication of Sunil Gangopadhyay or Shirshendu Mukherjee. The Puja songs would keep playing while we, a bunch of batch-mates from all over Mumbai, would endlessly snack on fancy food and chat.

My university years saw a shift of ‘allegiance’ to Notunpalli, the Puja started by Shakti Samanta at Bandra in 1972 as did all the major Bengali biggies of Bollywood, from Salil Chowdhury, Basu Chatterjee, RD Burman to Jaya Bhaduri and Amitabh Bachchan, who would earlier visit the Puja at Ramakrishna Mission at Khar. Now I would flock to the stalls of handloom saris, salwar suits, fashion dresses — some of which were set up by my cousins or friends. Rupa, Aloka-Tulika-Lipika, Mina Kakima and Latika Kakima — wives of actor Tarun Bose and playback artiste Talat Mehmood, sons and daughters of Dhruv Chatterjee and Asit Sen, seasoned CEOs and young bankers — the stimulating adda[9] here ranged from cinema to career choices, economics to politics.

*

Talking of Ramakrishna Mission, I am reminded of Manobina Roy, wife of Bimal Roy. Jethima[10] and my mother Kanaklata would set up a stall where they would sell papad and vadi, narkel and til naru, muri moa and kucho nimki[11]. These sesame, coconut or lentil balls were all made at home by Didimas[12], Kakimas and Mashimas[13]who lived in Rana Cottage near our house in Malad. If the Kumari Pujo[14]and Sandhi Puja[15]rituals were special for these seniors, Bijoya was super special for me and my friends. This post-immersion round of socialising to greet friends spelt many visits, to Bandra and Khar, Santa Cruz and Andheri, Goregaon and Borivali. And visiting the family of our parents’ friends meant not only naru-nimki, it could also mean chops, cutlets, cakes, sandwiches — goodies that were not so common in Bengali households 65 years ago, when sandesh and rosogolla, sweets made from cottage cheese, were also sold door-to-door, by men who brought them to our houses in aluminium trays tied in cloth!

*

That’s a faraway reality from what obtained in Kolkata where I spent some Puja holidays at my aunt’s (Ranjita Mashi’s) place on Motilal Nehru Road. It was opposite Deshpriya Park, where we children would report every morning of the five days, to help distribute the floral offering for pushpanjali and the prasad[16] in sal leaf bowls. Pandal hopping was a must, primarily on foot, as the pavilions designed with cloth themselves were works to admire. And on Dashami[17] evening, Haabu, Dipu, Reena, Minu and I would stand near the Rash Behari post office opposite Priya Cinema and watch the idols, sculpted with the signature of traditional idolmakers of Chitpore, being taken for immersion in the Ganga. What joy it was as we could watch all the Goddesses we’d heard of but not visited — even from Krishna Glass or Teish Palli! A much glamourised and glorified version is now held on Red Road, the main artery of the city, with the Chief Minister presiding over the Carnival of Immersion.

Twenty years ago when I returned to make my home in Kolkata, Deshpriya Park was still home to a Sarbojanin Durgotsav[18]. But it hit the headlines in October 2015 when mayhem broke loose crushing surging crowds who had assembled to view the 88-foot “Biggest Durga Ever.” Effectively the community celebration had become a cause for corporate branding and competition. Sponsors, in some cases, outnumbered the – neighbourhood — ‘parar‘ — volunteers. Reason? Perhaps because television was trying to grab eyeballs in every home. Even Kumari Pujo at Ramakrishna Mission was being watched on screens across the oceans. And as the Arts Editor of The Times of India, I was planning celebrity visits and artistic trophies for our Pujo Barir Shera Pujo [19]competition in high rise buildings and gated communities.

*

But what was the biggest change in observing Sarbojanin Durgotsav in Bengal? These public worship grounds had transformed into vast galleries where artists were staging the icons as installation art. These concept-driven pujas took leaves out of mythology but interpreted the goddess in the light of contemporary and universal concerns. Some were highlighting Her as a feminist force. Some as an embodiment of Nature. For some, She denotes the cosmic universe. Elsewhere crafts and looms got prominence. Family bonding was not forgotten. From the icons to the pavilions, from the chaalchitra to the fairy-light decoration — there was a unity of thought and execution. In the process, knowledge about practices in distant corners of our country, or of lifestyles several countries away from ours became accessible to the average person on the street.

There has been another interesting development. For years, the divas of Indian screen, from Bengal to Bombay, have inspired the Pals[20] of Chitpore. Sometimes she resembled Hema Malini, sometimes Madhuri Dixit. The demon too has been modelled after the politicians who are seen as foes.

At Arjunpur near Dumdum airport, the Third Eye of Durga is the nib of a fountain pen – as is the pointed middle of the three-pronged trident, trishul: “The pen represents wisdom and thought, and it is also the contemporary weapon to protest and fight,” explained Shampa Bhattacharjee. The artist from Delhi had designed the icon while her husband, physicist, created the atmosphere with rotating lights and floating balls – al in luminous steel.

*

Durga as a feminist force is perhaps the most natural interpretation of the goddess who was construed as a Goddess because evil demons had sought immunity against all other forms of power save a woman. Durga was conceived as Durgati Nashini — Destroyer of Misfortunes. The mace, the trident, the circular Sudarshan, the bow and arrow, the sword – every single weapon that empowered her was gifted by a God, be it Vishnu, Brahma, Shiva or Agni, Vayu, Varun, or even Yama. Read, the masculine forces. Perhaps that is why, the jagirdars and zamindars, under the nawabs and the British Raj worshipped Shakti, the icon of empowerment. The Raj families of the City of Palaces, the Debs of Shovabazar, the Chowdhurys of Behala, the Roys and Duttas of Kalutola and Nimtala, the Mullicks of Marble Palace or Rais of Andul – they still pay their obeisance to the Image of Shakti. And the celebration in the ancestral homes of these bonedi – once aristocratic – families are a tourist attraction.

Ironic that, during the struggle for Independence from the imperialists, She became the embodiment of motherland. Abanindranath Tagore’s iconic painting of her as the embodiment of sacrifice stays etched in our hearts and our souls to this day.

And when I stand before any invocation, in any form, in any corner of the subcontinent, these words of my father ring in my ears. “Imagine the map of India as you stand before Maa Durga. To her right are Lakshmi and Ganesha — the two realisations of Prosperity and Success — who are worshipped in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka. On her left are Saraswati and Kartik — representing Learning and Wisdom and Craft — worshipped in Assam, Bengal, Orissa, and the Deccan. At her feet is the Mahishasur, also depicted in our epic as the Dusht Ravan who ruled Lanka. And above her, reigning from the chaalchitra is Mahadev Shiva, identified with the Himalayas. Asamudra Himachal, from the mountain to the ocean, it is our motherland — Bharat Tirtha[21].”

*

The crux of it? Durga Puja is not merely the worshipping of a Hindu god. What started as a religious phenomenon in the households of the rich or powerful is no longer merely ritualistic. In this millennium, it is a vibrant celebration involving, at every step, the Indian thought and creativity, mind and heart, economy and management. It knits the masses in more ways than one. The castes and classes, the highs and lows of society — no one is left out of the festivity. It is a sociocultural happening. Year after year after year it is, in the truest sense of the term, Sarbojanin.

Small wonder the largest public art festival of the subcontinent has been recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage!

[1] Lawyer’s house

[2] Father

[3] Bud

[4] A woman actor

[5] Krishna, give us a place at your feet

[6] Flavour or essence

[7] Publisher, name means progress

[8] Bengali Immigrant Society

[9] Chit chat

[10] Paternal aunt

[11] Sweet and savoury snacks

[12] Grandmothers

[13] Paternal and maternal aunts

[14] Worship of girl child

[15] Evening prayers

[16] Snacks given out as blessings

[17] Last day of Durga Puja

[18] Community Durga Puja

[19] The Best Durga Puja Display

[20] The statue makers

[21] Pilgrimage of India

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and writes books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International