By Paul Mirabile

Vanitas Still Life, painting by Evert Collier(1640 –1708). Courtesy: Creative Commons

Back home in Madrid, having abandoned Adamov Plut to his posthumous fate, I was a bit surprised that neither the New York Times nor the Washington Post reported anything about the murder, not even a paragraph, or as the French so imagitively put it, an entre-filet ! I soon realised, due to this journalistic silence, that the time had come for me to give a full account of my relation to Mr Plut ; that the time had come for me to expose, publicly, by way of this revelation, his ‘mysterious murder’.

My information is of the surest sources for the simple reason that it was I who had Mr Plut murdered ! Yes, I ! And for reasons that shall be shortly disclosed. A mysterious man he might have been; however, his methods of acquiring priceless books and other inestimable valuables can hardly be called mysterious: Mr Plut was a vulgar thief, a scoundrel, an ingenious trickster whose singular flair caused much grief to many individuals, enraged those whose trust had been flouted.

It was in Istanbul, where I was invited to sojourn with an Armenian merchant, that I witnessed Mr Plut’s dupery. And if my naive friend fell for his crooked smile, I certainly didn’t swallow his high tale of returning to pay him for the two illuminated manuscripts my friend had graciously offered the blighter on condition that he be held accountable for them. His thick, coarse lips translated a smile that held contempt and disdain towards those who trusted him. So infuriated and insulted did I feel on behalf of my friend that that I reacted on a lightning urge and decided to follow him. I said nothing of this to my disbelieving companion, but left immediately in pursuit of my game — and game it was — for I, to tell the truth, had nothing more substantial to do at the moment and felt disposed for a good hunt.

I said that Mr Plut was a genius. Yes, in his own way. However, genius has its limitations. His arrogance and haughtiness knew no bounds, although he knew that his foul doings had attracted the attention of police and Interpol. Some may surmise that a certain paranoia drove him to invent individuals tracking him down like a wild boar or moose. No, no one was tracking him down except me, and that as subtlety as possible. In Uzbekistan, I actually chatted with him over a cup of coffee on two occasions disguised as a professor of Slavic philology, dressed in a quilted chapan robe and silk embroidered tubeteyka cap. There we sat in Samarkand, sipping our thick beverages in the vaulted bazaar at one of the storied cafés that dot the town. He was all smiles, obsequious and gold-toothed. I had the impression that I was dealing with a child or a mentally-dwarfed man whose sense of reality lacked all discernment or sagacity. I concluded that he had come into quite a bit of money, and never having had to work for a livelihood, traipsed about the world at his leisure, buying or stealing books, cheating people out of their invaluable collections. So self-indulgent and confident was he that he never saw through my masquerade as we conversed in broken Russian.

It was at that café where I learned about his fabulous treasure, as he called his book hoard. Only an idiot would have divulged this information to a perfect stranger, but as I said, Mr Plut’s contemptible demeanour caused him to fall into the most infantile traps. Traps that I began laying out for him, and that would lead to his downfall. For I had begun to design my own plan to relieve the rogue of his fabulous possessions, all the more so since he also let slip that his parents had passed away, and he had inherited the house. How I would make his treasure mine and ‘disinherit’ the owner still remained vague in my mind.

We departed as ‘friends’, as two strangers seeking an answer to the mystery of their existence. Or so I made him believe. Mr Plut appeared to me a dying species, a worldly aesthete, in spite of his extreme vulgarity and ponderous gait, whose debonair demeanour masked a loathing for his victims, a bent for the lowest duplicity, a gratification in spinning the most treacherous stratagems in order to allay his desire to prevail.

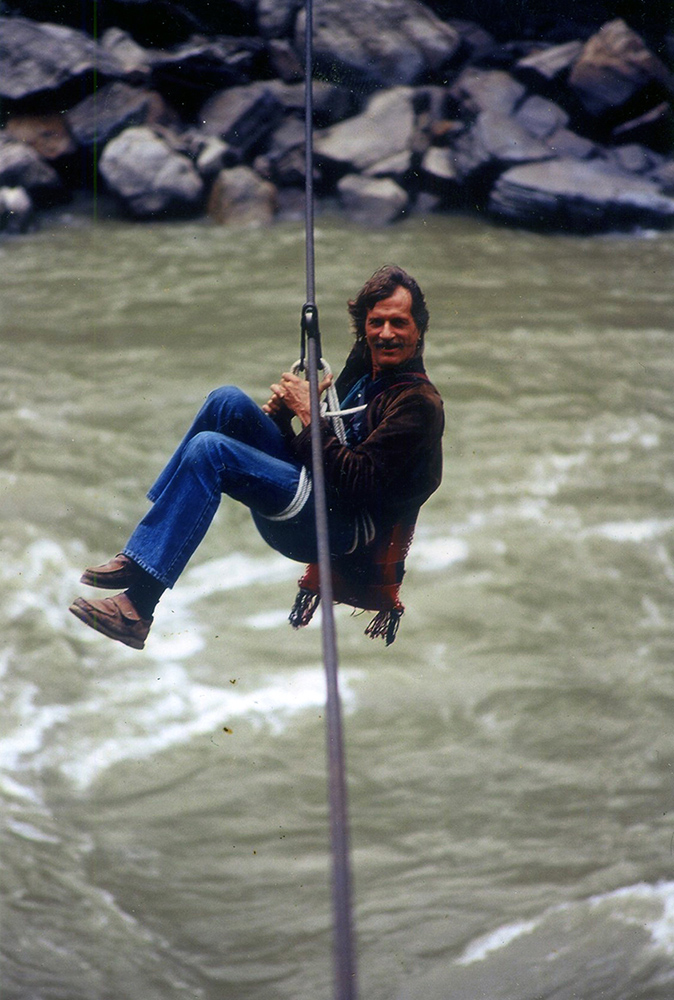

Mr Plut slipped out of Uzbekistan without my knowing it. He probably used his Russian passport, one of the four of five in his possession. I felt a twinge of misgiving. Had the fat fellow got on to me? After many enquiries, I finally discovered that he had crossed into China at the Xinjiang border, and was hastening towards the Yunnan. Why ? I hadn’t the faintest idea …

His brief sojourn in the town of Lijiang enabled me to catch up with him. My Chinese was fluent enough not only to query his whereabouts in that lovely town, but more important still, to learn of his new ‘purchases’, once I had questioned the director of the Dongba Museum of Culture. Mr Plut had planned to gone there to acquire several Naxi pictographic sacred books, which he did from a rather corrupt priest with whom he had been corresponding for some time, using a special code so as not to be unmasked by the Chinese authorities of the Centre. The director only learned of this a week after the unlawful negotiations had occurred, and three or four very valuable Dongba liturgical books had been stolen. It goes without saying that the rapacious priest was severely punished.

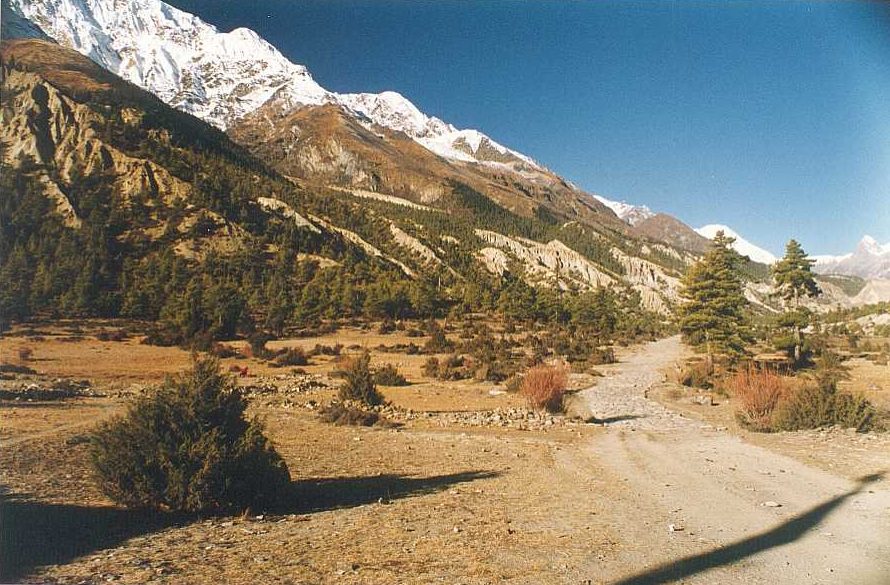

I immediately left Lijiang much to my displeasure for it was indeed a quiet, pleasant place, and set out in hot pursuit of the marauder. I followed his all too familiar scent through Nepal into North-western India to the Zanskar region where he put up for a while at the Phuktal Gompa[1], a strange spot to make a halt. But a perfect hideout to gain time in order for planning his next move, whilst at the same time inveigling in the most repulsive manner his generous hosts.

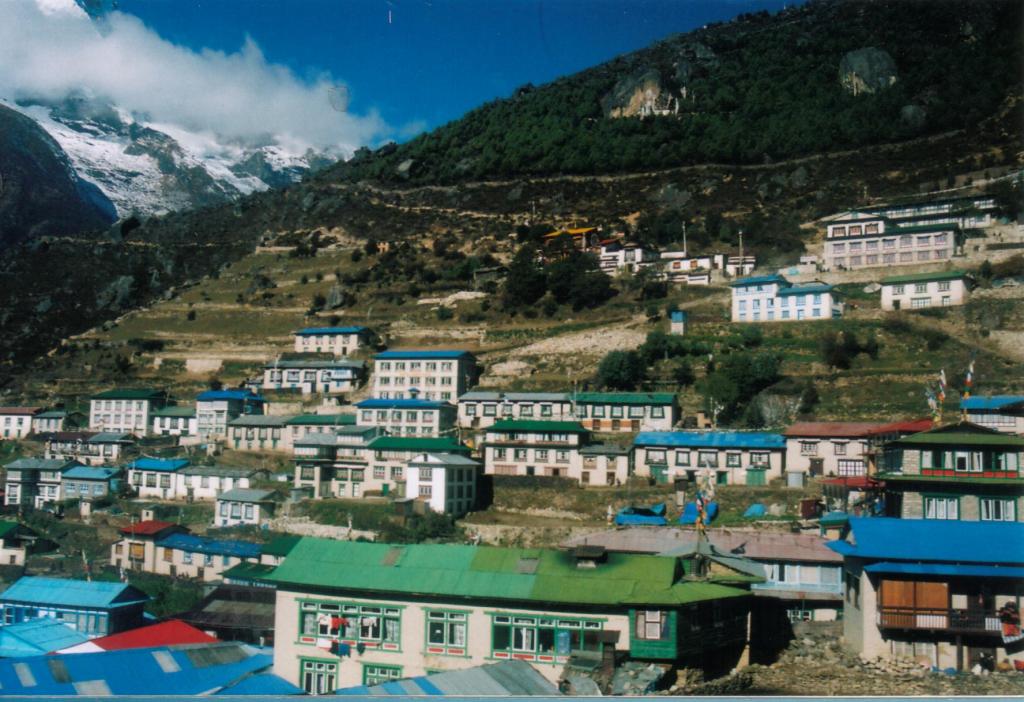

The monastery is nestled in the most remotest of valleys, ensconced within a cliff of tuft of fairy chimneys, crags and honey-combed spires which bulge black and red against the background of sandy, dazzling ash and cinerous tones of hemp. I had trekked there from Lamayuru in twenty days, and as I was to learn, Mr Plut had arrived there three days ahead of me, but by way of Padum. To gain the main entrance of the gompa, the pilgrim had to climb a steep path, keeping his or her right shoulder to the seventeen chortens[2] that mark the steep climb towards the vaulted entrance. I had shaved my head, grown a long beard and donned a woollen chuba tightened around my waist with a long colourful sash. It kept me warm, for in spite of it being Summer, the nights were very cold, and my cell had only a small wood-burning stove to keep me warm.

I spent three weeks at the monastery, sleeping on a ratten matting, eating skieu, tsampa and chappatti, drinking steaming salt-buttered tea off a chopsey — a low, small table — reading or gazing out of the little window that offered me a full view of the dusty, treeless courtyard below, where monks would mutter their mantras, and beyond into soundless nights whose stars were generally veiled.

Without Mr Plut’s slightest suspicions, I assisted at all the ceremonies, mornings and evenings, even vigils, while in the afternoon, I would venture out into the monastic complex, twisting and turning in the warren of lanes, under the low archways and high ladders, at times pursuing my promenades upon the rather precipitous mountain paths. As to Mr Plut, he hardly left his cell, and when we did cross paths, he most probably took me for a Buddhist pilgrim. Once or twice I sat near him in the prayer hall in the meditation grotto, but he never attempted to communicate with me, albeit he did not seem very deep in prayer or contemplation. He was probably scheming his next miserable move. His face had become terribly pale and flabby. His darting, black eyes seemed to have sunk deeper into their sockets. Unable to sit cross-legged on the low benches at the back of the prayer hall, he sat ‘western style’, staring off into the clusters of chanting monks, tilting his huge, bobbing head every so often to the banging drums, blowing ox-horns and tinkling triangles. Observing him from afar, I sought to sound his soul, to wring out his innermost thoughts, to extract from his evident lassitude and apathy his flight from both his victims and himself. But Mr Plut was a sphinx. Would he rise out of his own ashes when his hour came ?

I left the good monks three days after his departure, a hasty one indeed. And they were furious! The scoundrel had stolen several pustuks[3] and thangkas, and failed to pay for the prayer masks that he ‘purchased’. They implored me to find the culprit, inform the police and recover their stolen property. It was perhaps the beseeching words of the infuriated monks, after having received such incomparable hospitality from them, that my plans to have the thief killed began to germinate ! The theft was not only gratuitous, it exposed the very ugliness of the man’s heart, blackened by greed, cynicism and remorselessness. It would only be a matter of time before he tasted a soupçon of his own medicine.

Meanwhile the cat would play with the mouse, a rather fat mouse at that ! I boarded the cargo ship that took the fugitive from Karachi to Oakland via Japan. On the long, monotonous voyage across the Pacific, my ominous shadow crossed his at the most unsuspecting moments. Attired as a Pashtun merchant, bearded, long-haired and turbaned, Mr Plut sensed an onerous presence whenever he laboriously carried his huge body across the decks. How many times had my eyes penetrated his anguish, his torment, his pangs, not of compunction, but of incomprehension. He scented a sleepless menace pressing him. Fear inflamed his dark, beady, mirthless eyes like the burning incision of the trenchant knife.

Oakland … Sacramento … Reno … Tombstone … Boulder … Santa Fe … Saint Louis … Chicago … New Orleans … Birmingham … Miami … Atlanta and finally New York. Yes, New York, where the curtains would finally fall on this tragic fat figure. Where upon the stage of 8 million walk-ons, and against the backdrop of the grottiest of hotels, the last act of Mr Plut’s abominable performance would be played out.

His infatuation with Louis Wolfson amused me, as well as his grandiose project to write twelve stories in twelve different languages signed by twelve different authors. I found all this quite pompous and pathetic. A real exercise in self-indulgence to say the least. All this information I culled when I ‘accidentally’ met him in the ill-lit corridor of that hotel on Water street in downtown Manhattan. In New York, I played the role of a French researcher in mediaeval literature, a field that he completely ignored, in spite of possessing several manuscripts of Anglo-Norman stamp, apparently purchased (so he said ?) from a London book-seller. I pretended to be interested, taking the opportunity to study him closely. Besides, he was such an inveterate liar how could one believe anything he said ? He lied to curry favour and win confidence, only to swindle and steal from the naive and simple-hearted. Better to observe his eyes, his gestures, his bouncing from one tongue to another. These were all genuine signs of his distorted psychological make-up. To play my part well, I sported an immaculate white suit, orange tie, a pair of silver-rimmed glasses and spanking new alligator shoes. I had shaved my beard and moustache and had my hair cut very short, leaving a few gossamer wisps which touched the tips of my ears and fell bouncily on my forehead.

Every day I followed his Humpty Dumpty gait as he waddled to and from the public library, in and out of Central Park. And it was there, in Central Park, that I noted two blond-haired rough fellows slouching on a bench, eating the remains of fried chips or chicken sandwiches, cursing and making gross signs at the passers-by, drinking beer and spitting. They were seated at the same bench daily — the bench that Mr Plut walked by every day. They seemed to know him because they would hoot at him, call him names and ask for money. Fatso passed by without even a glance at them.

One Saturday, I decided to approach the two ruffians. They sized me up with obvious contempt, and made it perfectly clear that I was intruding on their ‘territory’. I sat down none the less, and exposed my scheme to be rid of Mr Plut once and for all, explaining how the culprit had cheated and robbed so many people. The two burly blokes, former marines in the Green Beret (or so they vaunted!) listened attentively as I unfolded my plan: Three thousand dollars for each if they would simply walk up to his room in the early morning hours, the night porter always being asleep, knock at his door and kill him, however, without any blood shed or theft of his belongings. It must be a murder without reason, without any sign of bestial violence. One of them suggested strangulation. Yes, excellent idea. It would thus be a ‘clean’ murder.

And so it was, very professional at that I must say. They were paid off, as agreed. And I left New York two days later, as planned, a very satisfied man indeed …

This all happened five years ago. Now … well, here is where my account ends and my confession begins. For you see, Mr Plut was never really murdered ! Those two ‘ruffians’ were in fact F.B.I. agents who had been trailing me since disembarking in California. To tell the truth, Interpol and local police had been following me since the Istanbul affair. How and why they began doing so I cannot say. During my trial neither the judge nor the prosecuting attorney afforded any information as how the F.B.I. learnt of my scheme, nor why they had decided, at one point in time, to cooperate with Plut. What was I convicted of ? What was my indictment ? As to my appointed lawyer, a young short-sighted clerk more than a seasoned lawyer, who could be easily cajoled by the ‘evidence’ against me, pliantly manipulated by the prosecutor, after he had taken the floor and had made an absolute fool of himself. He let out a sigh of relief when the judge pronounced a sentence of fifteen years instead of twenty-five! The wigged judge, a grotesque figure studded with huge warts, yawned throughout my lawyer’s deplorable speech for the defense, as well as during my feeble plea. There was no jury either to lament or to applaud his verdict. It was a trial held at ‘huis clos’[4], military style. I buried my face in my hands. As expected, my lawyer made no effort to appeal.

Had Plut sensed my innermost aversion towards him ? Or seen through my many disguises ? He was a clever man, and probably had hired detectives to learn why I was following him. The hotel room murder was staged. Plut lay recumbent on the floor, waiting for me to steal his papers so that I would be indicted for premeditated murder (although there was no murder!), of paying off hoodlums to commit this murder (although they were F.B.I. agents!) and the theft, which indeed it was (but fifteen years for that?) of his household papers, keys, and other official documents concerning his inheritance … and that vile short story of his.

So here I sit in my rancid smelling cell in Madrid, having been arrested at the aeroport on my arrival some five years ago, writing out this confession. I do not to repent mind you, I have no intention of atoning for my doings, nor avowing my sins. These words wrenched from my pen seek to vent the animosity and hatred I harbour towards that fat impostor who had the cheek to write me a letter from the Seychelles revealing how he had got on to me since Uzbekistan, and how our little cat and mouse game had amused him greatly : “You thought me a fool, deary, but I saw through your pusillanimous scheme in Samarkand ; that was some outfit, but you forgot the galoshes ! Not to mention your pilgrim weeds at Phuktal which truly charmed me, and your blazing orange tie in New York. Come, come, what French professor would ever sport an orange tie with a badly tailored, cheap white suit ?” The vicious irony underlining these sentences, along with a soupçon of cynicism caused me to gag. The blighter added in a post-script that he had sold all his books for a fabulous sum of money, and had retired from the world’s wearisome fair. In the envelope I found a photo of him sipping coconut juice, lying on the golden sands of a crescent-shaped beach under groves of swaying palm trees and an indigo blue sky. I laughed bitterly, and yet, in spite of my nettled nerves, pinned up the blasted photo in my lonely cell, a sort of souvenir of our enshrouded relationship …

One day at the prison library, browsing idly through a dull, detective story, I thought of Plut’s or Hilarius Eremita’s story The Enchanted Garden, which I had taken and read to amuse myself on the aeroplane to Buenos Aires. Had anyone ever published such ridiculous trash? To my horror, the answer came three days later whilst I rummaged through a new batch of literary magazines, some of which contained short stories in English, French and German. And there it was — The Enchanted Garden, by Hilarius Eremita, Plut’s pen name. I couldn’t believe my eyes — someone had published that rubbish ! Plut indeed had the last laugh, adding insult to injury, salt to my festering wounds.

I savagely tore out the pages of his story from the magazine, went to the toilet, ripped them into tiny pieces and flushed the filth down the bowl. So much for hiss ‘first of the twelve’ ! I shan’t be punished for it, no inmate in this prison reads any language besides Spanish, and that with a dictionary … I’m sure it was Plut who sent me that magazine to drive the knife deeper into my wounded pride. The miserable rat !

So here I sit at my iron table, staring at Plut’s photo as he sips his coconut drink under the blue skies and swaying palm trees whilst I sip my wretched thin noodle soup with strips of hard, nervy beef under a cracked, peeling, dirty grey prison ceiling …

.

[1] Monastery in Tibet

[2] The Tibetan word for stûpa, a Buddist shrine which initially housed the relics of the Buddha.

[3] Books used for Buddhist ceremonies written in Tibetan.

[4] Behind closed door without any public participation or observers. It is a French legal term.

Paul Mirabile is a retired professor of philology now living in France. He has published mostly academic works centred on philology, history, pedagogy and religion. He has also published stories of his travels throughout Asia, where he spent thirty years.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International