By Rhys Hughes

Prologue. There are fourteen mountains on the surface of the Earth higher than eight-thousand metres and recently it was found by observers on the ground they have all been sending postcards to the Royal Geographical Society but no one knows why…

Mount Everest. You say I am the tallest but that’s not quite true: I am just more obviously tall than you and everyone else you know. There is a mountain under the sea, Mauna Kea by name who is rather taller than me, 10,200 metres high as a matter of fact: it’s just a question of tact that she doesn’t loudly dispute my claim to fame (and yes, she’s a lady). And on the planet Mars stands Olympus Mons, highest mountain in our solar-system.

K2. I am not quite as lofty as my brother Mount Everest (see above) but he’s a softy when compared to me in terms of difficulty of climb. Mountaineers drop from fright on my slopes as well as from physical exhaustion. This is a warning, just a friendly caution. Don’t sleigh on my white suede snows. You can do anything but sleigh off my white suede snows.

Kangchenjunga. I invoke hunger in the bellies of those who try to get to my summit. A fellow named Crowley tried it back in 1905 and he survived while others of his team were avalanched into oblivion. He was snacking at the time in his tent on mints and thus was born his insistence that life is sweet.

Lhotse. I am the least prominent of the eight-thousanders despite the awfully vertiginous vertical relief of my South and Northeast Faces. I wouldn’t really mind swapping places with one of my sheerer fellows but I’m reluctant to make the offer. Should I stoop so low?

Makalu. I look like a pyramid, they say, but the comparison offends me most painfully. I am millions of years old, the pyramids, a few thousand. It should be the other way around, visitors to Egypt ought to gasp and cry: the pyramids look rather like Makalu. Now that’s the analogy that ought to apply.

Cho Oyu. My name in Tibetan means Turquoise Goddess and although I am modest I am pleased with the appellation. It seems I am the easiest of the eight-thousanders to climb but I don’t regard that as a disadvantage. Why be macho in the clouds? If you love Cho Oyu, she will be kind to you. Climb me and you’ll return like a human boomerang for I have the lowest death-summit ratio among the gang.

Dhaulagiri. I dazzle the eyes with my gleaming backside, and startle the minds of those who slide down my beauteous slopes. I hope and pray for a climber today to do something silly such as roll down Dhaulagiri all the way to the bottom after the snapping of his ropes: yes, to my shining base. It’s not a race, as such, because there can never be a winner, just a mess like a yeti’s dog’s dinner.

Manaslu. A serrated wall of ice hanging on the horizon like a bandsaw nailed to a door. That is how I am described by those who wish to ride my teeth: climb up one side and perch on my summit and you’ll find my mind is pure enough for gentler metaphors. I am not a tool, rarely the fool who tries to fix my own position in the scheme of things. In the valley below me snow leopards prowl and growl and so do you, softly, dreaming.

Nanga Parbat. When rats desert a sinking ship they expect it to really sink, not merely plunge its prow for a quick drink and then right itself again. That hurts, a betrayal of the laws of disaster. And the mice called climbers who scurried on my broad flanks when I sank into the spray of my own blown snows, crying avalanche! surely thought I had drowned for good in that illusory sea. But as you can see: I’m still here.

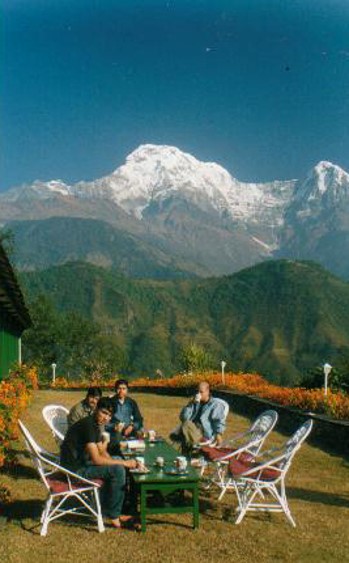

Annapurna. Now we come to the real test. I was the first eight-thousander to be climbed. Does that make me the easiest? Well, no. In fact I am the most dangerous of the fourteen. My fatality rate is twenty-five times as high as that of Miss Cho Oyu and my slopes are littered with those who have found their literal ever rest here. Get it? My propensity for making puns wasn’t mentioned in Maurice Herzog’s classic book about the first ascent of me. I wonder why? I took all his toes and most of his fingers with the aid of frostbite: a remarkable feat for him, paid for with both of his own astonishing feet.

Gasherbrum I. I have a brother who you will meet below, but in the meantime you ought to know that my eternal snows glow brightly across the region that is my home, and this is why I am mystified as to the origin of my nickname: the Hidden Peak. It’s inaccurate to my mind. Am I really so hard to find?

Broad Peak. My name is a physical descriptor but my views are broad too: I don’t care who or what climbs me. I welcome diversity. On July 23rd, 2016, a Frenchman by the name of Antoine Girard piloted a paraglider over my head. That’s a type of lightweight plane, but I didn’t complain. I never lodge objections with God.

Gasherbrum II. You have already met my brother a short distance above. He is above in height as well as in his location in this poem. I look up to him in everything, true, but he isn’t what I want to talk about today. No, I wish to briefly mention the Duke of the Abruzzi and also a certain Vittorio Sella, the former a brave aristocrat and intrepid mountain explorer, the latter the greatest photographer of high peaks who ever held a camera. Climbers wear trousers but their breath comes in pants: this pair arrived to reconnoitre me in 1909 and I was flattered, at least to the greatest extent that any giant is flattered by ants.

Shishapangma.

I was the last of the eight-thousanders

to be scaled, not because

I’m any harder to climb than I am to rhyme

but thanks to logistical

and political considerations. Less of that!

I wish to share with you

a little snippet that I find pleasant to think

about. When Tintin

was in Tibet, he travelled

with Captain Haddock towards me, looking

for a crashed plane. I

don’t recall either of them,

but I have been told their journey was true,

although they knew me

back then by my Sanskrit name, Gosainthan.

Epilogue.

Mountains rise and fall

like empires or supposedly solid walls.

Postcards are more

ephemeral than either,

especially when written in verse.

That’s the curse of time.

But the Royal Geographical Society

is never averse

to receiving them from

any interesting global feature that cares

to write a few lines.

Rhys Hughes has lived in many countries. He graduated as an engineer but currently works as a tutor of mathematics. Since his first book was published in 1995 he has had fifty other books published and his work has been translated into ten languages.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International