With Christmas at our heels and the world waking up slowly from a pandemic that will hopefully become an endemic as the Omicron seems to fizzle towards a common cold, we look forward to a new year and a new world. Perhaps, our society will evolve to become one where differences are accepted as variety just as we are fine with the fact that December can be warm or cold depending on the geography of the place. People will be welcomed even if of different colours and creed. The commonality of belonging to the same species will override all other disparities…

While we have had exciting developments this year and civilians have moved beyond the Earth — we do have a piece on that by Candice Louisa Daquin — within the planet, we have become more aware of the inequalities that exist. We are aware of the politics that seems to surround even a simple thing like a vaccine for the pandemic. However, these two years dominated by the virus has shown us one thing — if we do not rise above petty greed and create a world where healthcare and basic needs are met for all, we will suffer. As my nearly eighty-year-old aunt confided, even if one person has Covid in a remote corner of the world, it will spread to all of us. The virus sees no boundaries. This pandemic was just a start. There might be more outbreaks like this in the future as the rapacious continue to exploit deeper into the wilderness to accommodate our growing greed, not need. With the onset of warmer climates — global warming and climate change are realities — what can we look forward to as our future?

Que sera sera — what will be, will be. Though a bit of that attitude is necessary, we have become more aware and connected. We can at least visualise changes towards a more egalitarian and just world, to prevent what happened in the past. It would be wonderful if we could act based on the truth learnt from history rather than to overlook or rewrite it from the perspective of the victor and use that experience to benefit our homes, planet and all living things, great and small. In tune with our quest towards a better world, we have an interview with an academic, Sanjay Kumar, founder of a group called Pandies, who use theatre to connect the world of haves with have-nots. What impressed me most was that they have actually put refugees and migrant workers on stage with their stories. They even managed to land in Kashmir and work with children from war-torn zones. They have travelled and travelled into different dimensions in quest of a better world. Travelling is what our other interviewee did too — with a cat who holds three passports. CJ Fentiman, author of The Cat with Three Passports, has been interviewed by Keith Lyons, who has reviewed her book too.

This time we have the eminent Aruna Chakravarti review Devika Khanna Narula’s Beyond the Veils, a retelling of the author’s family history. Perhaps, history has been the common thread in our reviews this time. Rakhi Dalal has reviewed Anirudh Kala’s Two and a Half Rivers, a fiction that focusses on the Sikh issues in 1980s India from a Dalit perspective. It brought to my mind a family saga I had been recently re-reading, Alex Haley’s Roots, which showcased the whole American Revolution from the perspective of slaves brought over from Africa. Did the new laws change the fates of the slaves or Dalits? To an extent, it did but the rest as fact and fiction showcase were in the hands that belonged to the newly freed people. To enable people to step out of the cycle of poverty, the right attitudes towards growth and the ability to accept the subsequent changes is a felt need. That is perhaps where organisations like Pandies step in. Another non-fiction which highlights history around the same period and place as Kala’s novel is BP Pande’s In the Service of Free India –Memoirs of a Civil Servant. Reviewed by Bhaskar Parichha, the book explores the darker nuances of human history filled with violence and intolerance.

That violence is intricately linked to power politics has been showcased often. But, what would be really amazing to see would be how we could get out of the cycle as a society. With gun violence being an accepted norm in one of the largest democracies of the world, perhaps we need to listen to the voice of wisdom found in the fiction by Steve Davidson who meets perhaps a ghost in Hong Kong. Musing over the ghost’s words, the past catches up in Sunil Sharma’s story, ‘Walls’. Sharma has also given us a slice from his life in Canada with its colours, vibrancy and photographs of the fall. As he emigrated to Canada, we read of immigrants in Marzia Rahman’s touching narrative. She has opted to go with the less privileged just as Lakshmi Kannan has opted to go with the privileged in her story.

Sharma observes, while we find the opulence of nature thrive in places people inhabit in Canada, it is not so in Asia. I wonder why? Why are Asian cities crowded and polluted? There was a time when Los Angeles and London suffered smogs. Has that shifted now as factories relocated to Asia, generating wealth in currency but taking away from nature’s opulence of fresh, clean air as more flock into crowded cities looking for sustenance?

Humour is introduced into the short story section with Sohana Manzoor’s hilarious rendering of her driving lessons in America, lessons given to foreigners by migrants. Rhys Hughes makes for more humour with a really hilarious rendition of men in tea cosies missing their…I think ‘Trouser Hermit’ will tell you the rest. He has perhaps more sober poetry which though imaginative does not make you laugh as much as his prose. Michael Burch has shared some beautiful poetry perpetuating the calmer nuances of a deeply felt love and affection. George Freek, Anasuya Bhar, Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Dibyajyoti Sarma have all given us wonderful poetry along with many others. One could write an essay on each poem – but as we are short shrift for time, we move on to travel sagas from hiking in Australia and hobnobbing with kangaroos to renovated palaces in Bengal.

We have also travelled with our book excerpts this time. Suzanne Kamata’s The Baseball Widow shuttles between US and Japan and Somdatta Mandal’s translation of A Bengali lady in England by Krishnabhabi Das, actually has the lady relocate to nineteenth century England and assume the dress and mannerisms of the West to write an eye-opener for her compatriots about the customs of the colonials in their own country.

While mostly we hear of sad stories related to marriages, we have a sunny one in which Alpana finds much in a marriage that runs well with wisdom learnt from Kung Fu Panda. Devraj Singh Kalsi has given us a philosophical piece with his characteristic touch of irony laced with humour on statues. If you are wondering what he could have to say, have a read.

In Nature’s Musings, Penny Wilkes has offered us prose and wonderful photographs of the last vestiges of autumn. As the season hovers between summer and winter, geographical boundaries too can get blurred at times. A nostalgic recap given by Ratnottama Sengupta along the borders of Bengal, which though still crossed by elephants freely in jungles (wild elephants do not need visas, I guess), gained an independence from the harshness of cultural hegemony on December 16th, 1971. Candice Louisa Daquin has also looked at grey zones that lie between sanity and insanity in her column. An essay which links East and West has been given to us by Rakibul Hasan about a poet who mingles the two in his poetry. A Bengali song by Tagore, Purano shei diner kotha, that is almost a perfect trans creation of Robert Burn’s Scottish Auld Lang Syne in the spirit of welcoming the New Year, has been transcreated to English. The similarity in the content of the two greats’ lyrics showcase the commonalities of love, friendship and warmth that unite all cultures into one humanity.

Our first translation from Uzbekistan – a story by Sherzod Artikov, translated from Uzbeki by Nigora Mukhammad — gives a glimpse of a culture that might be new to many of us. Akbar Barakzai’s shorter poems, translated by Fazal Baloch from Balochi and Ratnottama Sengupta’s transcreation of a Tagore song, Rangiye Die Jao, have added richness to our oeuvre along with one from Korean by Ihlwha Choi. Professor Fakrul Alam, who is well-known for his translation of poetry by Jibonanda Das, has started sharing his work on the Bengali poet with us. Pause by and take a look.

There is much more than what I can put down here as we have a bumper end of the year issue this December. There is a bit of something for all times, tastes and seasons.

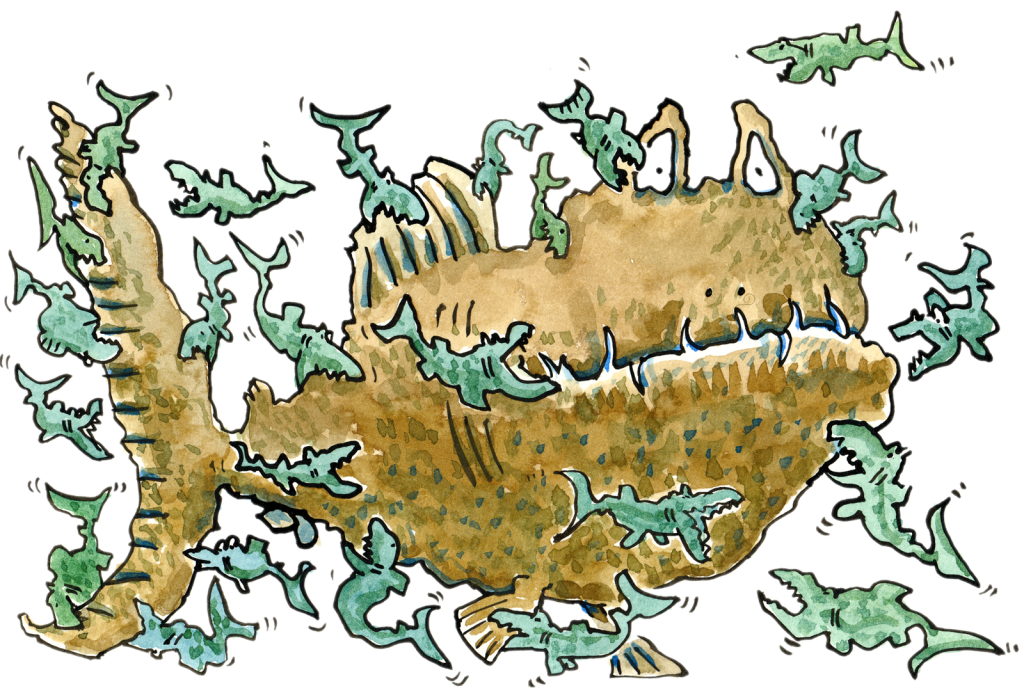

I would like to thank my wonderful team for helping put together this issue. Sohana Manzoor and Sybil Pretious need double thanks for their lovely artwork that is showcased in our magazine. We are privileged to have committed readers, some of who have started contributing to our content too. A huge thanks to all our contributors and readers for being with us through our journey.

I wish you a very Merry Christmas and a wonderful transition into the New Year! May we open up to a fantastic brave, new world!

Mitali Chakravarty