Book Review by Somdatta Mandal

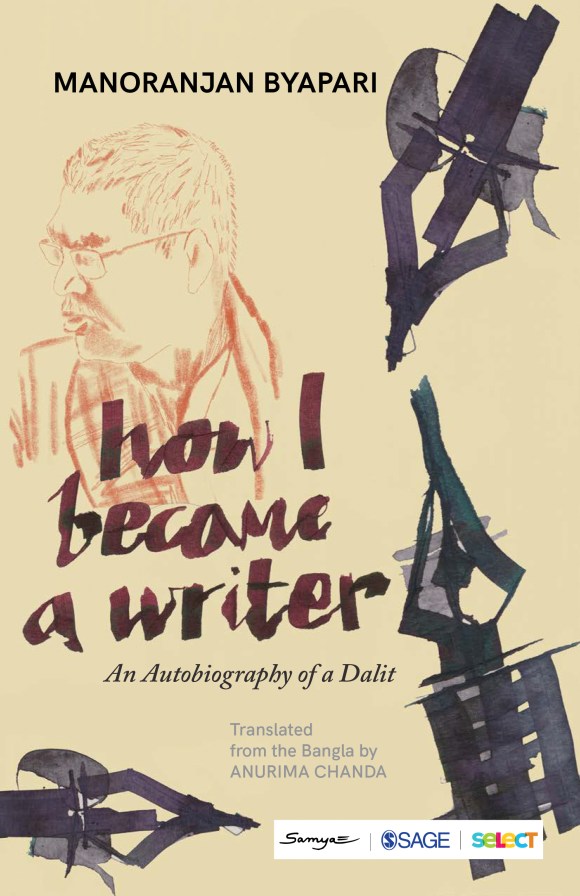

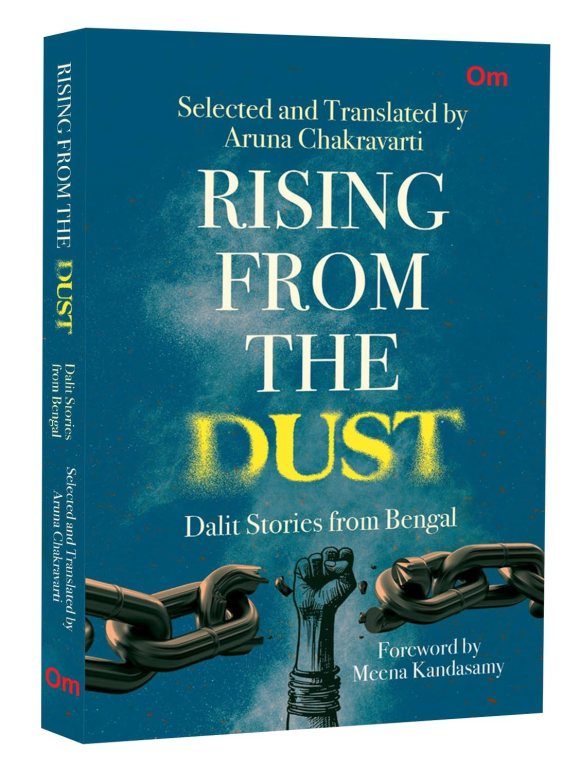

Title: Rising From the Dust: Dalit Stories from Bengal

Selected and Translated by Aruna Charavarti

Publisher: Om Books International

Though Bengali Dalit writing is comparatively newer compared to Dalit writing in Marathi and other Dravidian languages, nevertheless it has already carved a niche for itself in a significant way. The main difference between the Dalit writing emanating from other regions of India and that of Bengal is that whereas the thrust area elsewhere is primarily on the untouchables, the downtrodden and the way the Dalits have been marginalised in society for a long time, in Bengal the problem is further complicated by caste and class issues which is not so significant elsewhere. This collection of twelve Dalit short stories from Bengal, carefully selected and translated by Aruna Chakravarti, spans a long period and what distinguishes it is the gendered lens that explores the Dalit woman’s cause and holds it up to the light.

There is a difference in the style of narrating the Dalit experience from writer to writer and accordingly it can be divided into two groups. In the first category are writers who themselves belong to the Dalit community and their writing stem out of experiential feelings. The second group of writers belong to the upper castes, and their writing stems from a feeling of empathy for the marginalized and the downtrodden. Spanning a long period of almost a century, Aruna Chakravarti has decided to blend both these categories and has meticulously translated the dozen stories from well-known writers to those a little lesser known. While literary stalwarts like Mahasweta Devi, Saratchandra Chattopadhyay, Tarashankar Bandopadhyay and Prafulla Roy share their profound understanding of the Dalit woman’s fears and traumas, hopes, dreams and aspirations, contemporary voices from the Dalit community itself like Manoranjan Byapari, Bimalendu Haldar, Manohar Mouli Biswas, Kalyani Thakur Charal, Anil Ghorai and Nakul Mallik explore aspects of survival and social ostracisation with both sensitivity and angst. On the one hand we have centuries of oppression being still carried upon these subaltern people, and even within that restricted space, we also often find protest and upheaval that the doubly marginalized womenfolk attempt to revolt against.

In the opening story titled “Fortress” by Manoranjan Byapari, we find Nakul’s widow Sarama, unwillingly forced to sell her body to oppressive menfolk everyday finds her unique way of protest by deliberately copulating with her ex-husband Ratan who is inflicted with venereal disease, thereby driving out all her fear and henceforth would ‘welcome every touch’ and ‘would wait outside her door in delicious anticipation.’ In Bimalendu Haldar’s “Salt” we are shown how a fisherman Madhai who works for his employer Nishay Ghosh, goes missing and his wife Chintay, collecting three other suffering women registers their protest in a unique way. In “Shonkhomala” Manohar Mouli Biswas tells us a relatively contemporary and true story relating to the grabbing of agricultural land in the fertile Singur area by the government for setting up of the Tata Motor Factory. It tells us of how Shonkhomala Dom, a Dalit woman, changes her name to Tapashi Malik and is gangraped and murdered because she was unwilling to give up her land and organized a protest march instead. Incidentally, till date, the court case for identifying the murderer and the rapists of Tapashi Malik is unresolved.

Another very touching story “Illegal Immigrant” by Nakul Mallick brings in the plight of refugees from erstwhile East Bengal coming to India after the partition. It tells us of the plight of an extremely poor jhalmuri seller called Madhav who, along with his wife Shefali, lives in a slum beside the train track and somehow manages to eke out a decent living. When Madhav is picked up as an illegal Bangladeshi immigrant and thrown out of the country, his wife’s life goes haywire as she goes to the Petrapole border looking for her husband in vain. Kalyani Thakur Charal deliberately adds the word ‘Charal’ meaning ‘Chandal’ or ‘untouchable’ to her name in order to take pride of her Dalit identity. In “Motho’s Daughter” she tells the story of one Nishikanta who wants to get his children educated first and foremost and is frustrated in the end because his stray son gets married to a woman who doesn’t encourage education. Anil Ghorai, another powerful Dalit writer, tells an interesting story about Larani, belonging to the tanner caste, her relationship with Hola Burho, a dhol[1] repairer and his son Pabna. The main thrust of the story “The Insect Festival” is of course the attack of locusts in the village and how the majority of the illiterate villagers take resort to superstitious rituals in order to ward off the menace instead of confronting the situation in a scientific manner.

As mentioned earlier, each story by the four empathetic writers goes on emphasizing the pressures of caste and class upon the lower classes of people in different situations. In “The True Life Story of Uli-Buli’s Mother” Mahasweta Devi tells us the story of a helpless woman who becomes a destitute after being thrown away for having four daughters. She lives under the delusion that someone has stolen her young twins Uli and Buli. Again in “Nalini’s Story” she draws a beautiful pen picture of Nalini, who after being abandoned by her husband, lives with her grandson and ekes out her living by working as a maid. Years later, her estranged son along with his wife and her landlord Gobindo all desire to take possession of her house by arranging an elaborate shraddha ceremony for her estranged husband. Nalini understands their ploy and, in the end, she puts her foot down, unwilling to be in eternal debt for the extravagant rituals proposed by them.

Prafulla Kumar Roy’s “Snake Maiden” gives us an inside story of the gypsies or nomads who are known as ‘bedyes’ and who deal with snakes and charms. Here Shankhini is the mistress of a band of bedeys who come and settle in Sonai Bibir Bil for the season and accidentally meets her ex-lover Raja saheb. She is in a quandary because he wants her to renounce the bedeni’s life and settle down in one place and turn into a farmer’s wife. The tug between domesticity and the age-old tradition of this nomadic gypsy tribe’s rituals and customs is elaborated through the rest of this interesting story. The powerful storyteller Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay gives us two stories with totally different locales and characters. In “The Witch” he elaborates upon the idea of a woman who is defined as a witch and is ostracised by society because she is said to cast an evil eye upon everything she sees. She dies an agonising death in the end as her dark and unholy blood oozes out from her veins. Incidentally, even to this day the idea of identifying certain low caste woman as witches and even burning them to death persists in several villages in rural Bengal and such superstitions are not overcome at all.

In the second story “Raikamal”, Tarashankar gives us an in-depth picture of a Vaishnav community, their rituals and their manner of living. The protagonist Kamalini had to abandon her crush on Ranjan because he belongs to another caste, weds Rasik who consumes poison in the end out of jealousy and ultimately Kamalini has to live all alone. Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s eponymous story “Abhagi’s Heaven” is once again a depiction of Bengali society strictly divided according to caste lines. In this story, Kangali’s mother Abhagi, an untouchable, a ‘duley’ by caste, watches the funeral pyre of a Brahmin lady and imagines her going to heaven in a golden chariot. She nourishes the desire to be cremated in a similar fashion when she dies, but after her actual death she is denied the privilege of being burnt and has to be buried near the riverside as per societal norms.

The stories in this collection capture the essence of a way of life marked by the enduring defiant spirit of the dispossessed and the marginalised. This is a must-read not only for literary enthusiasts, but also for students and scholars of Dalit and caste studies, development studies, Indian literature in translation and gender studies. In her foreword, Meena Kandasamy categorically states that “every short story in this collection holds together a precious, precarious universe – the old order continues with its oppression, the new is struggling to be born; everyday life is a struggle and yet, struggle itself is the terrain, where life, liveliness, and being alive come into their full glory.” This translated volume is therefore strongly recommended for non-Bengali readers who are not aware of the nuances of Bengali Dalit writing at all and it will dispel the notion that all kinds of Dalit writing cannot be brought together under a single umbrella. Kudos to Aruna Chakravarti for her excellent selection and meticulous translation of these one dozen stories.

[1] Musical instrument akin to a drum but hung from the neck

.

Somdatta Mandal, critic and translator, is a former Professor of English at Visva Bharati, Santiniketan.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International