By Ravi Shankar

The decision to retire was a long, tough, and protracted one. The traditional wisdom always gave out doctors never retire. But we needed time to ourselves. We had long and fulfilling lives and now was the time to take things slow. The body was ageing and required more time to complete various activities. Some tasks were no longer possible.

I still remember the first day I met Rajendra on the orientation day of the Family Medicine residency program in upstate New York. Rajendra was from Jiri in the Himalayan country of Nepal. For a few decades, Jiri was the gateway to the Everest region. Then the hikers and mountaineers started flying to the air strip at Lukla. Roads were also progressing further and further in the country. We grew closer during the residency. We shared many interests including nature, hiking, photography, creative writing, and a strong empathy for the underdog. Our friendship slowly deepened, and by the end of the residency we decided to spend the rest of our life together.

We were also different in so many ways. I was a girl of mixed German and Colombian heritage. My family was well-to-do, and I had a privileged childhood. Raj was from a poor family and had to face many struggles in his life. He went to medical school on a government scholarship. Like most graduates of the Institute of Medicine in Kathmandu he then concentrated on being selected for a residency in the United States. Even in the early eighties this was a long, hard struggle.

He did a few ‘observerships’ and research attachments. He eventually went on to become a chief resident and we both worked for around two years in the Northeast health system after residency. Soon we had to decide on what to do next. I would have liked to continue in the United States. Raj however, was increasingly considering whether we should go back to Nepal. I told him that though I had never even visited Nepal I was OK with whatever he decided.

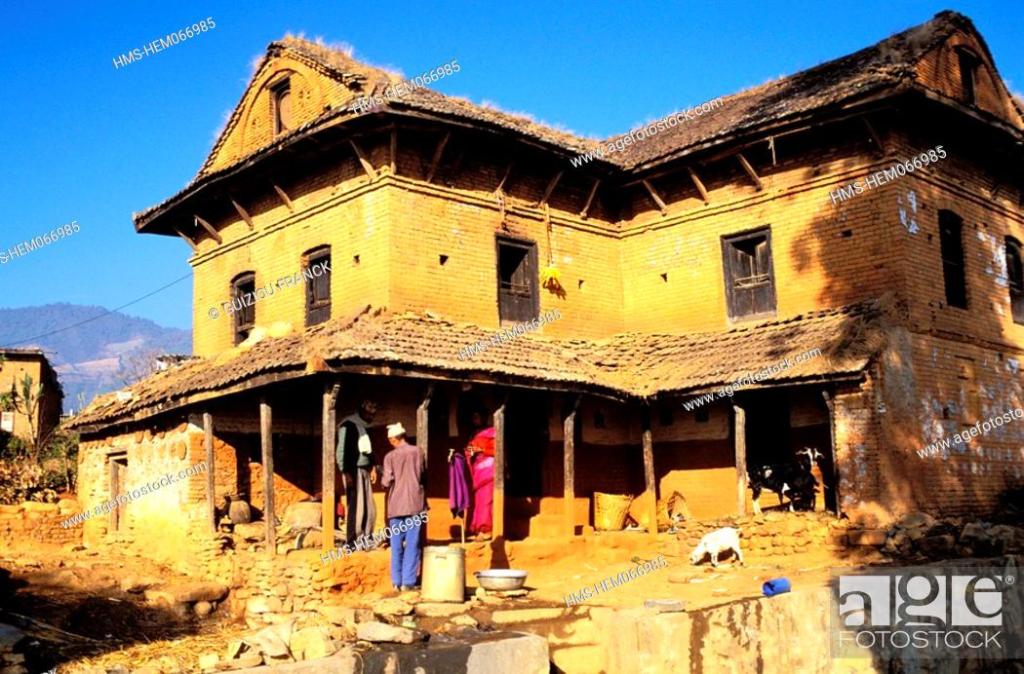

Though his family had settled in Jiri, Raj was a Newar. His full name was Rajendra Shakya. The religion of the Newars was complex tapestry of Hinduism and Buddhism. His family home was at Bungamati, a Newar village in Lalitpur district at the southern part of the Kathmandu valley. Newar Gods and Goddesses were complex and had both good and more wrathful aspects. Women were considered ritually impure during menstruation and were not allowed into the kitchen during this period, and they could not visit temples. In some rural parts of the country, the Chaupadi system was still followed, and women were banished to a cow shed during their periods. The Newars had their own caste system, and the concept of purity was important. In the Kathmandu valley the Newars had their ritual feasts (bhoj) and the buffalo was the most important animal in Newari cuisine.

The cow was sacred and killing one was a grave sin, but the poor black buffalo was fair game. I often reflected on this injustice. We first worked at the United Missions to Nepal hospital at Tansen at the foothills of the Himalayas. Tansen was a small town with a significant Newari influence and the hospital was the major and often only source of health care for a large population. The hospital was overcrowded, and we had to deal with a variety of patients. The houses for the doctors were lovely and picturesque, and we had a great community of both Nepalese doctors and expats. We stayed in Tansen for nearly a decade. There were delightful walks in the surrounding hills and a rather long hike to the Rani Mahal on the banks of the Kali Gandaki, often called the Taj Mahal of Nepal.

There was an opening for a doctor couple at Khunde hospital in the Everest region and as he was from Jiri, Raj wanted to apply. The hospital was at a height for around 4000 m and was set up by Sir Edmund Hillary. The hospital provides care to local residents, hikers, mountaineers, and porters from the lowlands. Initially it was a very isolated existence. Later a satellite phone was set up and eventually an internet connection followed. We dealt with all kinds of patients. The weather was cold, but I loved the picturesque cottage near the hospital. The region was becoming a popular trekking region and during the peak seasons of autumn and spring several thousand trekkers passed through.

Patan hospital is one of the old and famous hospitals of Nepal located in the city of Lalitpur also known as Patan in the Kathmandu valley. Migration of doctors to developed nations was a major challenge for Nepal and the Institute of Medicine was not very successful in producing doctors for the country as most graduates left for developed nations. The importance of a family medicine/general practice programme was understood by the policy makers and the Patan Academy of Health Sciences (PAHS) was set up. MD was the postgraduate medical qualification in the country and a MD in General Practice and Emergency Medicine (MDGP) was started in this institution.

We were among the faculty for this program, and we were now working at Patan hospital. We had some family land at Bungamati and built a traditional Newari style house. There were smiling mustard fields around though the area was rapidly urbanising. Flowers grew well. In winters, the Himalayas could be seen on a clear day but air pollution and dust made this a rarer phenomenon.

My brother had retired and settled in our family land on the outskirts of Albany, New York. We had a rather large plot of land, and I was thinking of settling near him. We had followed different life trajectories, and it would be nice to spend some together in the autumn of our lives.

Our work at Patan Hospital was hectic. After long conversations we decided to retire from the hospital and offer our expertise to the MDGP program as Emeritus Professors. Raj’s sister and brother had retired and were now living in Bungamati. Patan hospital would have loved for us to stay on.

We decided to divide our time between Albany and Bungamati. Summers in Albany and winters in Bungamati. Winters in upstate New York can be harsh and unforgiving. The long flight between the two locations will be a challenge as we did not handle long flights well. Let us see what fate had in store for us. Our son was a vascular surgeon in New York and we could be near to him. We were happy that we finally decided to retire and spend time with our families and our grandchildren. It was time to explore the road less travelled!

.

Dr. P Ravi Shankar is a faculty member at the IMU Centre for Education (ICE), International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He enjoys traveling and is a creative writer and photographer.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International