By Meredith Stephens

In an ideal world I would sleep in every morning and enjoy a leisurely breakfast, but I can indulge in no such luxury because I have a border collie. Her name is Haru. She has an elongated body, a pointy white snout scattered with black dots, one black ear and one black and white spotted ear, all-knowing brown eyes, feathered forelegs, and a bushy tail with a white tip. She looks more like a cross between a fox and a border collie than a pure border collie. As soon as she hears my voice when I wake up, she starts whining from the courtyard below, nagging me to take her for a walk. I much more looking forward to my breakfast than the walk, but Haru is the opposite.

One Tuesday, as usual, I affixed her leash and walked her towards the esplanade. Haru has memorised the route. She strained in front of me to the point where we crossed the road and then continued to drag me towards the pedestrian crossing. Then she made a beeline for the stairs leading down to the beach. I released the leash and threw the ball down to the sand. She raced down the stairway ahead of me and ran to catch the ball. In the winter months along this coastline, dogs are allowed to run off the leash as long as they are under the owner’s control. I was joined by a throng of other dog lovers and their canines, running to catch balls. Haru is interested neither in other dogs nor other people. All she cares about is the ball. Other dogs approached her and chased her, but she’s indifferent, solely focused on the ball in my hand.

This is good for me because I get exercise when I otherwise would not, and experience vicarious pleasure in her excitement at retrieving the ball. Maybe this is more fun than breakfast after all. However, my walk last Tuesday was unlike those of previous weeks. I spotted an entire fish washed up on the shore amongst the seaweed. I had never seen this before on my daily beach walks over the last five years. Then I looked up and saw a rounded shape of a mammal a few hundred metres in the distance. I walked towards it, and once up close I realised that it was the head of a dolphin. “Sorry,” I said, feeling complicit in the damage wreaked by climate change. Haru was normally quick to sniff out a carcass and chew it, but she showed no interest.

The next day I chatted to a neighbour who told me that on her beach walk she had seen a range of species washed up on the beach that she didn’t know existed. We were witnessing the aftermath of an algae bloom, known as Karenia Mikomotoi, from September 2024. This had arisen in response to a rise in the sea surface temperatures of 2.5 degrees. The recent storms in June 2025 had washed the bodies of these sea creatures ashore. On my next beach walk I came across a small stingray, completely intact, directly in my path. I had seen stingrays before swimming in the shallows but never washed up on the beach. It was so beautifully formed that I could tell it had met an untimely death. Something untoward and unusual had happened. Again, Haru showed no interest in the stingray, despite usually being interested in decaying fish or animals.

Weeks later I continued to spot fish washed up on the shore that I have never seen before. I came across much smaller fish a couple of centimetres long, some slightly larger fish, and another small stingray. These were the kind of colourful fish that I would see when snorkelling in pristine waters, not washed up on a suburban beach. Haru continued to ignore these dead creatures and skipped along the beach anticipating my ball-throwing. Or perhaps she somehow sensed they contained toxins. At least she was unlikely to be poisoned by eating them.

She delights in catching not only one ball that I throw her, but sometimes two. She doesn’t like to relinquish a ball, so I have another one on hand to throw her so that she can chase all the while holding the first one in her mouth. After chewing the ball down to a smaller size and squashing it, she can sometimes fit two into her mouth. Once she has managed this, she runs away from me into the wintry waters, oblivious to the cold, triumphant that she has two balls and trying to get as far away from me as she can in case, I try to take one away from her. Sometimes she skips through patches of the dirty foam left by the algal bloom.

I wish I could provide a happy ending to this story, but the algal bloom is not predicted to end soon, so my idyllic morning and evening beach walks with the oblivious Haru are likely to be punctuated with sightings of innocent marine creatures being washed ashore, victims of climate change and warming temperatures.

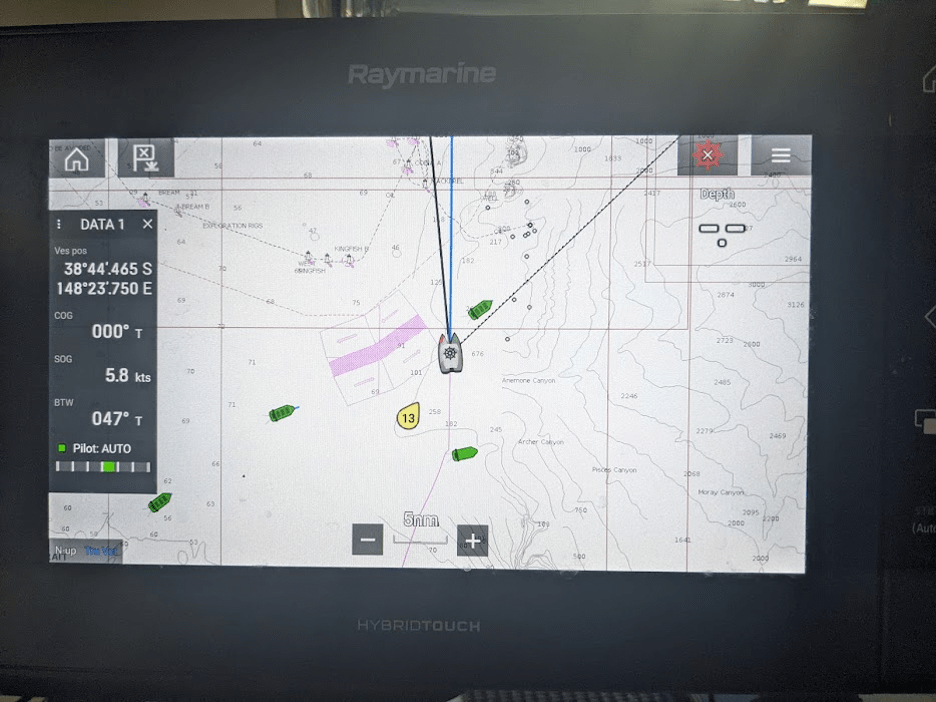

One consolation occurred the day my fiancé, Alex, and I left the mainland to sail across Investigator Strait to Kangaroo Island. Over the years there has never been a crossing during which we have not seen dolphins. In the back of my mind, I feared that this would be the first time. An hour into our crossing, Alex heard the familiar splash of breaking water and sighted a pod of dolphins. Not only that, once in the bay at Kangaroo Island, we spotted a sea lion. Thankfully, the marine life that can escape the algae is still undisturbed. I hope the scientists will find a way to address the marine heatwave so that life in our oceans can again thrive, and beachgoers can be spared the sight of these innocent creatures being washed up on local beaches. We can’t simply delegate to the scientists, though. Witnessing this marine carnage is a strong impetus for ordinary citizens to live more sustainably.

Meredith Stephens is an applied linguist from South Australia. Her recent work has appeared in Syncopation Literary Journal, Continue the Voice, Micking Owl Roost blog, The Font – A Literary Journal for Language Teachers, and Mind, Brain & Education Think Tank. In 2024, her story Safari was chosen as the Editor’s Choice for the June edition of All Your Stories.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International