By Farah Ghuznavi

It was time to give up the fight.

Shifting from the uncomfortable position on her side, Chhaya sat up. There was no way she was getting a nap on this flight.

For her surrender, she was rewarded with a beaming smile from one of her fellow passengers. The man, who had earlier introduced himself as Henrik Something-or-the-other, had not stopped talking – or so it seemed to her – for the past five hours. She was grateful that they had less than two hours of flight time remaining before they landed in Copenhagen.

Reaching the departure gate in Dubai, Chhaya had noticed Henrik almost immediately. Tall and lean, his well-groomed silver hair seemed a little at odds with his flamboyant clothing: a zipper-festooned biker jacket, red tie, white shirt and navy jeans, with a black cowboy hat jauntily perched on the extended handle of his cabin baggage, for good measure.

A short time later, she located her aisle seat, only to find him comfortably ensconced between her and the young Indian man sitting by the window. Curtly acknowledging his introduction, she ignored the twinkle in his eye and dived into a report on refugee relief activities, indicating, she hoped, a total lack of interest in further conversation.

A man dressed like that had to be working his way through some form of midlife crisis, Chhaya figured, albeit one that had arrived late. She had no idea how accurate her assessment actually was. But she was determined not to be a spectator at Henrik Whatnot’s travelling circus. Besides, she was determined to be well-prepared for the donor meeting in Copenhagen.

By the time their meal had been served, Henrik was on first-name terms with all the cabin crew members. He had started by sharing the holiday photos on his phone with Giselle. A tall blonde from Munich, she seemed unaccountably interested in his safari experiences at Kruger National Park. And even Chhaya had to admit that the picture of him bottle-feeding a lion cub was rather cute.

“Was this your first trip to South Africa, sir?” Giselle asked.

“Call me Henrik! Yes, it was, and I am thinking of buying a third home there. Now that I’m retired, my wife and I have more freedom to travel. A doctor’s life isn’t really designed for leisure, but for the last couple of years, we’ve been spending our summers in Denmark and our winters in Thailand, where my wife is from. I’m making up for lost time, so to speak – though my wife’s convinced I travel too much!”

Chhaya concealed an inward shudder at this instance of yet another older white man picking up some young Thai woman on a beach holiday, and taking his submissive Asian flower home to keep him warm in the frozen north. The stewardess, who was probably thinking the same thing, did an even better job of hiding her distaste.

“So you met your wife on your travels, sir – I mean, Henrik?”

“Yes, but perhaps not in the way that you are thinking,” said Henrik, smiling. “I was hiking through northern Thailand, when I stumbled across a village tucked away in the hills. There were no hotels, so I rented a room for the night in someone’s home. The family had a son who was visiting from Bangkok. He was the only one who spoke good English, so he translated our conversation for the others, while we ate the delicious food his mother had cooked for us.

“In the middle of the night, there was a knock on the door, and the young man came in to say that his neighbour’s child was very ill. He asked if I could help. I did what I could, but it was touch and go for a while, because the boy was burning up. I spent the next few days looking after him. He lived with his mother and aunt, who had the unenviable job of plucking and cleaning slaughtered chickens at a nearby poultry farm.

“I ended up staying in that village for three months. That’s how long it took me to persuade the boy’s aunt that I would make a good husband. Even today, my wife Su doesn’t like spending time in Bangkok, so we decided to build a house in her village. You never can tell what fate has in store. My marriage to the world’s kindest woman was built on a foundation of chicken guts, late nights with a sick child, and her determined resistance to the advances of a strange foreigner!”

By the end of his story, they were all smiling, even Chhaya.

She was less impressed when Henrik decided to buy gifts for his beloved wife from the duty-free trolley after dinner. Examining a platinum bracelet stud with diamonds, he asked the steward Jeffery, what he thought of it.

“It’s a bit over the top, isn’t it?” the man said. And then, perhaps remembering that his job was to actually sell things – the more expensive the better – the steward made a quick recovery, adding “Though I suppose it depends on your wife’s preferences. It is a very beautiful bracelet!”

“Yes, but I think you may be right. My wife is a woman of simple tastes. I think she would prefer this one.” He selected a slim gold bracelet cunningly crafted into three interwoven strands, before moving on to the perfumes. “Which of these fragrances do you think she’d prefer?” he asked Jeffery.

“I don’t really know, sir…” he said, hesitating.

“But you must have some preference!” Henrik said. “What would you buy for a woman – for your wife or girlfriend?”

Since Jeffery looked decidedly ill at ease, Chhaya intervened. “Why don’t you ask one of the women Henrik? I’m sure they would be happy to give you some advice.”

The look of relief on Jeffery’s face made Chhaya wonder if perhaps giving away aftershaves was more his style than perfumes. Summoning his co-worker, a petite brunette, to the trolley, Jeffery said, “Marta, this gentleman would like some suggestions about which perfume to get his wife for a special occasion.”

Rolling her eyes at Jeffery, Marta nevertheless obliged. With her more savvy assistance, Henrik finally selected a crystal Baccarat bottle of Guerlain Idylle, spending the tidy sum of nearly 1500 euros on the two items. “I’ve been away a long time, so I have some making up to do where she’s concerned!” he joked.

Appalled at his extravagance, Chhaya couldn’t help thinking about how much better that money could have been spent in the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, where she and her team found themselves working under increasingly frustrating conditions.

There was no point in making such comparisons, she knew, but it was infuriating when people threw away money like that in a world where others were desperate. And with money to burn, why was this guy travelling economy anyway?

Deciding she had had enough of the strange man and his stories, Chhaya turned on her side, jamming in the earplugs that she had cadged off Jeffery, and willed herself to sleep.

Meanwhile, Henrik turned to speak to the young man on his right, who reluctantly surrendered his headphones and his plans for in-flight entertainment. As Chhaya persisted with her abortive attempt at napping, Henrik proceeded to chat with Sunil, a nerdy youth with well-oiled hair, who was on his way to the US to study Engineering.

“So you’re going on a full scholarship? How wonderful! Your family must be very proud,” Henrik said.

“Yes, they are. I would never have got the scholarship without the sacrifices my parents made for my education,” Sunil said. “But now I am facing some difficulties.”

“Why? What’s wrong?” Henrik said.

“Well, it was my mother’s fervent wish that I get engaged before leaving for America, but I just could not find a suitable girl. My parents tried everything. They matched horoscopes, discussed nice girls with my uncles and aunties, and identified a number of prospective brides.”

“But do you want to get married so soon?” Henrik said.

“Oh yes, I have no problem with having the engagement now and getting married after I return from the US,” Sunil assured him. “It is just that none of the girls was right for me. What I mean is, several of them were beautiful, but there was always something I didn’t like about them. And also, too many of them wore glasses!”

“Ah, but you mustn’t be so finicky, young man! You can’t pick a bride simply for her beauty, and think that’ll be enough to keep you happy. Beauty is all very well, but after a while, its effects wear off. The important things in a marriage are humour, and companionship – a wife who is smart enough to understand what you need, and to tell you what she needs. And the girls who wear glasses are probably the smarter ones!”

“But my wife must be beautiful! You see, I am intelligent, but I am not very good-looking. So when we have children…”

“You want them to have her looks and your intelligence?”

“Yes!”

“But Sunil, as George Bernard Shaw famously pointed out, you must realise that it could also work out the other way around! And if they were to have your looks and her intellect, surely you would want her to be intelligent too?” Henrik laughed. “Not that there’s anything wrong with your looks, of course!” he added cheerfully.

With Sunil as his captive audience, Henrik continued to expound on his theories regarding marriage. Trying to sleep, Chhaya ground her teeth as the sub-standard airline earplugs forced her to listen in; though she had to admit that the older man did make a number of good points.

In the end, Sunil reached the same conclusion, saying “Yes, Mr Henrik, I think you are right. I will take another look at the bio-datas of some of the girls with spectacles.”

In the end, Chhaya gave up all hope of sleeping and sat up once again. Marvelling at Henrik’s powers of persuasion, she decided to try for an attitude adjustment. It helped when the object of her ire turned to ask Chhaya what line of business she was in.

“I’m a development worker, actually,” she said.

“Oh?” Henrik’s eyes lit up. ”What’s your area of specialisation? And if you don’t mind my asking, where are you from?”

Some imp of mischief made Chhaya reply, “Well, where do you think I am from?”

“To tell you the truth, I’m having a hard time figuring it out. I want to say Thailand, because you remind me a bit of my wife, but your name doesn’t sound Thai. Are you Malaysian? Or Nepali?” Henrik said.

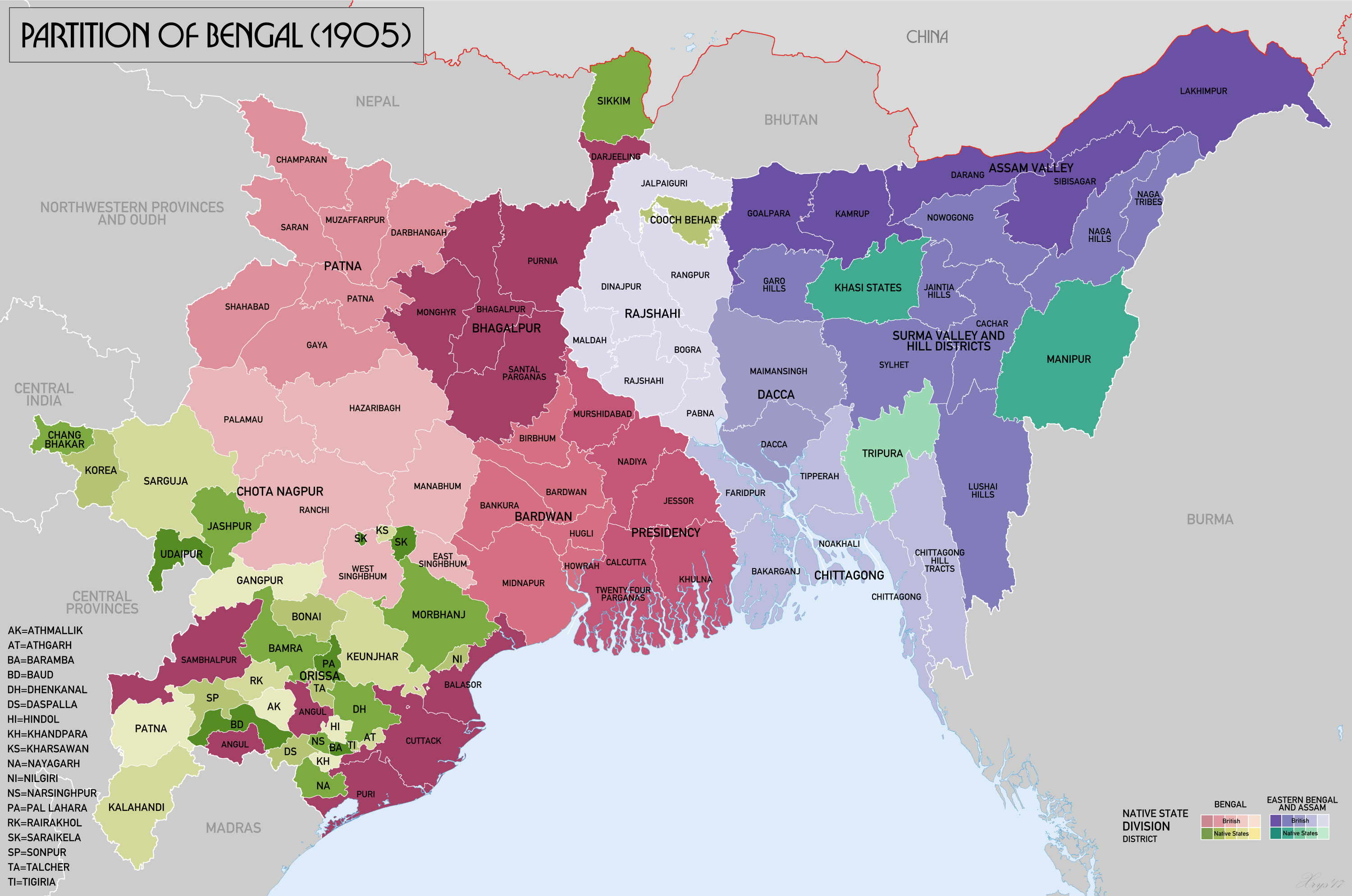

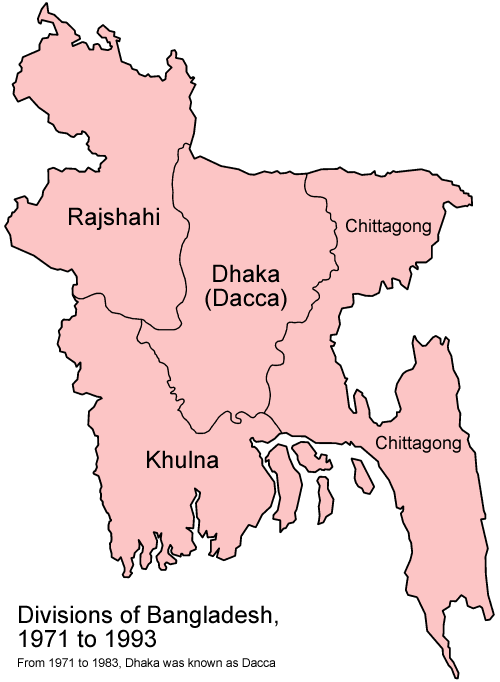

“That’s what most people think,” Chhaya said. “But actually, I’m from Bangladesh.”

“Well, that’s a country facing some challenges right now!” said Henrik. “I was surprised when your government decided to let the Rohingyas in a couple of years ago. So many of them too. I just wish European governments were half as generous when it came to refugees!”

“Yes, if only!” Chhaya laughed. “But coping with the influx has presented enormous logistical challenges for those in my line of work. As well as for Bangladesh as a country, of course.

“Actually, that’s why I’m going to Copenhagen right now, to address the donor consortium that funds my organisation.” She gestured at the report she was holding, “So I need to sound informed and authoritative.”

“Have you actually been to the camps yourself?”

“Yes, several times. I was there very recently, just a couple of days ago. Things are a mess right now, but we have to deal with the realities on the ground. And there’s also some talk about this new disease, COVID 19, that’s popped up out of nowhere. It could be disastrous if it makes its way to Bangladesh, given our population density. And people are living cheek by jowl in the refugee camps already!

“To make matters worse, China’s pretty close by for us, so the threat is very real. Unless, of course, it miraculously disappears the way MERS or SARS did. Still, I’m actually quite proud of Bangladesh for opening the borders to the refugees from Myanmar despite what it’s costing us.”

Chhaya smiled briefly before continuing, “As for Aung San Suu Kyi — I can’t understand how, after benefiting from the international human rights movement’s support for decades, she could turn her back on the Rohingya refugees like this!”

“I guess her hands are tied, to some extent,” Henrik said. “The military are still in charge in Myanmar, after all.”

“That’s true, but I don’t understand how she can possibly deny what’s happening there. And it infuriates me when she draws a false equivalence between the elements carrying out this ethnic cleansing, and whatever supposed disruption the Rohingyas have caused in Myanmar!” Chhaya said.

“I can’t argue with you there. But unlike her fellow Peace Prize-winner Mandela, Suu Kyi is ultimately a politician. And to politicians, the most important thing is power – regardless of how they get it.”

“I wish the Nobel Committee had never given her that Peace Prize. She certainly doesn’t deserve it!”

“I suspect the Norwegians are thinking the very same thing!” Henrik said.

Looking into those shrewd blue eyes, Chhaya realised that she had underestimated the older man. He was no buffoon, whatever the reason for his gregariousness. Or indeed, what some might call his garrulousness.

His interest in the challenges posed by the Rohingya presence in Bangladesh, and his awareness of Suu Kyi’s fall from grace indicated a surprising knowledge of global events, something she would not necessarily have associated with the average Dane, given the sheltered lives they led.

Though of course, Suu Kyi’s Nobel Prize had originated in Henrik’s part of the world, in neighbouring Norway. And she had met enough Scandinavian activists and development workers to know that most of them cared passionately about sharing resources to help create a better world.

“Unfortunately, there is no precedent for stripping someone of the award. So I think we’d have been better off giving her the Ig-Nobel Prize rather than the Nobel!”

“Is there such a thing?” Chhaya asked in disbelief.

“Oh yes, very much so. They identify recipients for it every year. Not that anyone is eager to be an award winner for that one! But, on a different note, does your organisation accept private donations?” Henrik asked.

“Yes, we do, actually!” Chhaya replied, surprised. “We have a special PayPal account for this campaign, because it’s a humanitarian emergency.”

Henrik took down the details, before taking out his mobile phone. Even as she gave them to him, a cynical part of Chhaya’s mind wondered if this was more of the man’s posturing, or whether a donation would ever materialise. She did not have to wait long to find out.

Jeffery appeared in response to Henrik pressing the call button. “I wonder if you could help me get online for a few minutes?” Henrik said.

Chhaya knew that it was expensive to use the Internet while the flight was airborne, but it didn’t seem to deter Henrik. Jeffery, happier with this request than he had been with the previous one, helped him navigate the process. As Chhaya watched, Henrik entered the staggering amount of five thousand euro, and sent off his contribution.

The remaining flight time passed quickly, as they discussed the situation. And after she had collected her baggage upon landing, Chhaya looked around to say goodbye to her strange companion, and to thank him one last time. But by then, Henrik was nowhere to be seen.

Chhaya gave a mental shrug. Henrik had asked for her email address, but she doubted she would hear from him again. He had already made his donation, and a generous one at that. It was surely enough to allow him to wash his hands and his conscience clean of the matter.

*

Evelina Morales was having a bad day. After an exhausting flight from the Philippines, she had landed in Copenhagen to discover that her employer was going to be late picking her up. Not that she cared. Despite being tired, she was in no hurry to be reunited with Mrs. Solgaard. Because though her employer liked to insist that Evelina address her as Anne-Karin, the young woman was under no illusion that it made their relationship any less formal.

Anne-Karin Solgaard’s soaring career trajectory meant that Evelina’s services as an au pair made up a key element of her support system. With two young children, Anne-Karin could not have sustained her meteoric rise as a right-wing politician without Evelina’s help at home.

Nevertheless, Evelina could not shake the sense that her employer viewed her as more of a robotic nanny service than a human being. And although Anne-Karin often touted Denmark as an ideal society where everyone, including workers, had good lives and proper weekends off, Evelina noticed that this did not stop her employer from asking her to work on a Saturday or Sunday if Anne-Karin needed her services, as she all too often seemed to.

Nor was Evelina’s job an easy one. The children, both boys under the age of five, displayed a boisterousness that verged on being hyperactive. Danish permissiveness with respect to child rearing made things even harder. So while Anne-Karin fondly referred to her boys as “chaos pilots”, Evelina could not help thinking that she might have been less indulgent if she herself had to deal singlehandedly with the chaos that they created.

But if Evelina could not quite be sure how her employer viewed her, she was left in no doubt of Anne-Karin’s general dislike of immigrants, particularly those who came to Denmark from Somalia and other hotspots. “If only the Muslims would make an effort to integrate!” she was often heard saying to her admirers. “You’d think they would be grateful to have a new life here, but it’s unbelievable how resistant some of these people are to adopting Danish values.”

Evelina made it a point never to react when Anne-Karin made remarks like that, but she drew the line when her employer suggested she read the autobiography of Ayaan Hirsi Ali. “She’s a remarkable woman, you know, Evelina. She identified the threat that Muslims pose to Europe long before most of us were aware of the danger. And she knows what she’s talking about — she grew up in Somalia!”

Aware of Ali’s incendiary views on religion from her conversations with a Somali friend, Evelina could not remain silent. “Thank you, but I find some of her ideas too extreme. I mean, according to her, the Norwegian terrorist Anders Breivik felt that censorship of his writings on Christian superiority left him “no choice” but to commit murder! Breivik massacred dozens of children on Utøya. And this vile man actually expressed admiration for her in his manifesto!”

“I haven’t heard her views on Breivik,” Anne-Karin replied, unruffled. “But she is right to talk about the need to combat Islamic terrorism.”

Despite her own worries about the Muslim separatist struggle in the Philippines, Evelina despised people like her boss, whose populist rhetoric recycled tired stereotypes to score cheap political points. So, though she allowed the statuesque redhead to have the last word, the young Filipina left the book untouched where it lay.

To make matters worse, Evelina knew that quite apart from her hostility to immigrants in general, and Muslims in particular, Anne-Karin’s identity as part of a tiny minority of Danes attending evangelical churches meant that she often viewed other Christians – especially Catholics like Evelina – with a degree of suspicion. And as a Christian herself, Evelina could not help thinking that Anne-Karin and her Pentecostal friends held views that would not pass the litmus test that they were so fond of applying to key life questions: namely asking, “What would Jesus do?”

That this group’s political opinions reflected the general hardening of Danish attitudes towards foreigners did not make her employer’s racist comments any easier for Evelina to swallow. No matter how much she worked, Evelina was regularly subjected to Anne-Karin’s assertion that Denmark was too soft in letting in the migrants “flood in” to exploit its admittedly-generous welfare system.

Evelina’s friend Aaden, a young Somali man who had fled the brutal civil war, certainly had little time for people like her employer. “How’s Ol’ Sunshine today?” Aaden would ask, smiling. It was a long-standing joke that her sourpuss employer’s surname included the word for sun, “sol” — even if it was because she had taken her husband’s name. Such merriment at her expense was probably not the outcome Anne-Karin had in mind when she packed her nanny off to the introductory language course where Evelina had met Aaden.

“If I knew what would make her happy, Aaden, I would do it just to get that look of disdain off her face. You know what I mean?”

“Yes, but nothing you can do is likely to change anything! Let’s face it, she just hates foreigners. What’s worrying is that someone like her is doing so well in Danish politics!”

“I guess she represents all the people who think like her. Such nasty people shouldn’t be the ones making decisions that impact other people’s lives…”

“Well, she certainly seems to have no problem having foreigners around when they’re changing diapers and ‘airing’ the dog!” Aaden said, referring to the literal meaning of the Danish term used for dog-walking.

“That’s because she can’t afford to hire a Dane to do the work that I do!” Evelina retorted.

“Don’t forget, most of them think they’re too good to be doing this kind of work. I’ve never seen so many people who want all the crappy jobs done for them, but don’t want to let in the workers who’re willing to do those jobs,” Aaden replied.

Now, nursing the overpriced cup of coffee she had bought in order to occupy a table at the airport snack bar, Evelina reflected on how unhappy she felt being back in Denmark.

Nobody at home understood. For them, it was a great opportunity to travel and earn good money for what was, after all, a relatively simple job. Too simple, Evelina thought. Was this all that being a straight “A” student throughout school and college was worth?

To add insult to injury, Aunty Nancy kept telling her, “You might even meet some nice Danish man. And then you could stay on there!” Evelina did not have the heart to tell her that marriage was probably the last thing on the average Danish man’s mind. But letting her family down by quitting her job was just not an option. And it did at least allow her to save some money towards a university degree.

Her despondent musings were interrupted by a smiling stranger. As the silver-haired gentleman standing in front of her enquired if he could share her table, Evelina looked around at the lack of available spaces and assented with whatever grace she could muster.

“Are you okay?” the man asked her, after a moment. “You look a little tired.”

The concern in his eyes prevented her from taking offence. “I’m all right. It’s just been a long flight…” And before she knew it, Evelina found herself telling a stranger what she had been unable to share with her family.

He listened patiently, before saying, “I’m so sorry you’re having such a difficult time. This is certainly not the best time to be an outsider in Denmark. But you know, there are many Danes who feel exactly the same way that you do. Especially people working in the development sector, like me, who’ve seen more of the world.”

“Oh, do you travel a lot for work?” Evelina asked.

“Yes, or at least, I have done more of that recently. I’m a doctor, you see. Once I retired, I wanted to do something useful. So now I volunteer to work in countries that are experiencing humanitarian crises – though I’ll admit that I wasn’t brave enough to help with the Ebola outbreak.”

“So where have you been?” Evelina asked.

“All over the place, really,” her companion replied. “In fact, it’s caused a lot of trouble in my personal life. My wife is, understandably enough, fed up with my absences! Still, I didn’t expect…” he paused.

“Is something wrong?” It was Evelina’s turn to ask.

“Yes, well… I was expecting my wife to pick me up, you see. But I just received the text message she wrote last night. She says she’s leaving me. So there won’t be anyone to meet me at the house now – and I was so excited about coming home.”

“I’m really sorry!” Evelina didn’t know what to say. He seemed like a nice man, but she could understand that his wife might get tired of waiting for a husband who was always travelling to faraway, and potentially dangerous, places.

“It’s alright,” he said. “I’ll manage. It’s not entirely unexpected, but I did hope that things wouldn’t come to this. I’ll just go on to my next assignment straightaway. I’m volunteering at the refugee camps in Bangladesh, where they’ve been dealing with the Rohingya people, who are fleeing persecution in Myanmar. ”

“Of course, I’m sure you’ll be fine,” Evelina said, feeling awkward. She didn’t even know the man, but it made her oddly sad to think of him returning to an empty house with a broken heart. Still, it was good to be reminded that not all Danes were as unfeeling or self-absorbed as Anne-Karin.

“This would never happen in your country, would it?” her companion said, making an attempt at humour. “I suppose people aren’t often lonely in cultures like yours – not unless they want to be alone, of course”.

“You’d be hard put to find yourself alone in the Philippines, even if you wanted to be!” Evelina said.

They smiled at each other briefly, before the man continued, “I should head home now. But before I go, could I ask you for a favour?”

Evelina nodded, a little wary. He didn’t look like a creep, but you could never tell.

She waited.

“I bought a present for my wife, you see – and I just can’t bear to carry it around. You’d be doing me a great favour by taking it off my hands…” he said, looking at her hopefully.

Evelina was in a quandary. She did not want to accept a gift from a stranger, but she could understand why the poor man might find the poignant reminder of his changed circumstances too painful.

“Please!” he said, “I would be very grateful.”

Reluctantly, Evelina agreed. Straightening to his full height, the stranger handed her a small duty-free bag. Then he turned and walked away, disappearing into the excited crowds that had gathered to greet their friends and families.

*

Well, that took care of one thing, Henrik thought. He had observed the sad-looking young woman for a while before deciding that she would be the recipient of his duty-free purchases. Hopefully Evelina would enjoy the bracelet and perfume.

Poor girl, what a nightmare her employer was! But what could you expect from a member of the Danish right-wing? The rising tide of hostility to immigrants in Denmark was part of a wider global picture that Henrik struggled to understand, though he was familiar with the othering rhetoric of “us” versus “them”.

Muslims in particular were often demonised, and when you got down to it, were about as welcome to most Europeans as the Rohingyas were to the Buddhists in Myanmar. It bothered Henrik that his fellow Danes’ commitment to the egalitarian values underpinning their society did not seem to extend beyond their borders.

On the other hand, human beings were complicated creatures, full of contradictions. You just had to look at him to see that, after all.

He had gone from being shy Henrik Ahlberg, to a globetrotting sophisticate capable of talking to complete strangers at great length – even when he wasn’t speaking a word of truth!

Actually, that was not entirely fair: it was true that he was a doctor. And the life story he told was, after all, the life he could have had. If only he had been brave enough to go in search of it before…

As for his imaginary Thai wife, Henrik gave himself points for coming up with such a highly believable detail. His countrymen’s weakness for Thai women was well-known, though Henrik himself would have been happy with a woman from any country, if she had only loved him in the way that he had longed for his entire life.

He had waited patiently for years to meet the woman of his dreams. Preoccupied by his work, and distracted by fantasies about the future, it was too late by the time Henrik realised that the love of his life had stood him up. Unlike him, perhaps she had got tired of waiting. Which meant that now, the woman who should have been his wife was probably having a great life with someone else.

There was nothing Henrik could do about those lost opportunities. But when the unexpected remission from his illness materialised, he decided to use whatever time he had left – and nobody seemed to know exactly how long this could be, since estimates ranged from ten months to as many years – to make up for all the time he had wasted. The South African safari was just the first step in that process.

It was a pity, he thought, that he had never lived up to his dream of working for Doctors Without Borders. Helping people survive disasters in the darker corners of the globe would have been a worthwhile use of a life, and probably far better than what he had used his life for, at least to date.

He had felt a pang when he was describing his dream retirement career to Evelina. But to his younger self, viewed from the safety of Scandinavia, that kind of work had seemed too dangerous. It took his diagnosis to show him just how close to home danger could lurk.

It was inspiring to see people who cared so much about their work, like that girl on the plane, Chhaya. She had been so offended by the extravagance of his duty-free purchases! It was written all over her expressive face, reflected in the furious knitting of those dark brows set over her long-lashed brown eyes.

She had no way of knowing that he was “in character” at the time. Or that money was the one thing that he did have, since both love and time were in short supply.

She was a feisty little thing, that one, Henrik thought, chuckling inwardly. Not that she would thank him for describing her as “little”, he suspected. Even if he did tower over her five foot frame. The encounter with her reminded him of something that his Indian friend Jayesh had said, about a proverb to the effect that small chillies often pack the biggest punch.

And meeting people like her also validated his choice to travel economy, which he preferred because of the diversity it offered, in comparison to the comfortable predictability of business class.

Remembering that he still had Chhaya’s card tucked away in his wallet, Henrik had the sudden thought that medical volunteering might not be such a far-fetched idea, even now. After all, he suspected they needed all the help they could get in those refugee camps.

And if he followed through with his plan, then perhaps on some future flight he would even get to tell his fellow travellers a true story or two.

.

Farah Ghuznavi is a Bangladeshi writer, whose work has been published in Germany, France, Austria, UK, USA, Canada, Singapore, Nigeria, Nepal and India. Her story, ‘Judgement Day’, was awarded in the Commonwealth Short Story Competition 2010. She was also the writer in residence with the Commonwealth Writers website in 2014.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL