Acknowledging our past achievements sends a message of hope and responsibility, encouraging us to make even greater efforts in the future. Given our twentieth-century accomplishments, if people continue to suffer from famine, plague and war, we cannot blame it on nature or on God.

–Homo Deus (2015), Yuval Noah Harari

Another year drumrolls its way to a war-torn end. Yes, we have found a way to deal with Covid by the looks of it, but famine, hunger… have these drawn to a close? In another world, in 2019, Abhijit Banerjee had won a Nobel Prize for “a new approach to obtaining reliable answers about the best ways to fight global poverty”. Even before that in 2015, Yuval Noah Harari had discussed a world beyond conflicts where Homo Sapien would evolve to become Homo Deus, that is man would evolve to deus or god. As Harari contends at the start of Homo Deus, some of the world at least hoped to move towards immortality and eternal happiness. But, given the current events, is that even a remote possibility for the common man?

Harari points out in the sentence quoted above, acknowledging our past achievements gives hope… a hope born of the long journey humankind has made from caves to skyscrapers. If wars destroy those skyscrapers, what happens then? Our December issue highlights not only the world as we knew it but also the world as we know it.

In our essay section, Farouk Gulsara contextualises and discusses William Dalrymple’s latest book, The Golden Road with a focus on past glories while Professor Fakrul Alam dwells on a road in Dhaka , a road rife with history of the past and of toppling the hegemony and pointless atrocities against citizens. Yet, common people continue to weep for the citizens who have lost their homes, happiness and lives in Gaza and Ukraine, innocent victims of political machinations leading to war.

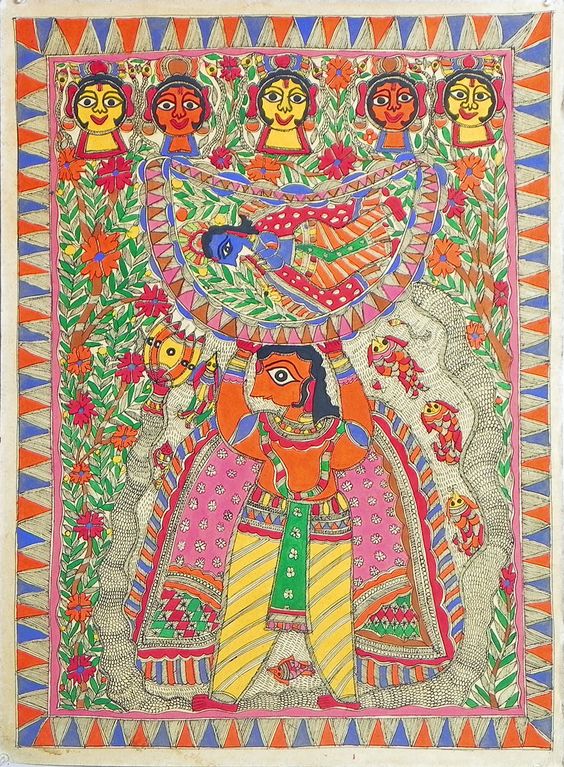

Just as politics divides and destroys, arts build bridges across the world. Ratnottama Sengupta has written of how artists over time have tried their hands at different mediums to bring to us vignettes of common people’s lives, like legendary artist M F Husain went on to make films, with his first black and white film screened in Berlin Film Festival in 1967 winning the coveted Golden Bear, he captured vignettes of Rajasthan and the local people through images and music. And there are many more instances like his…

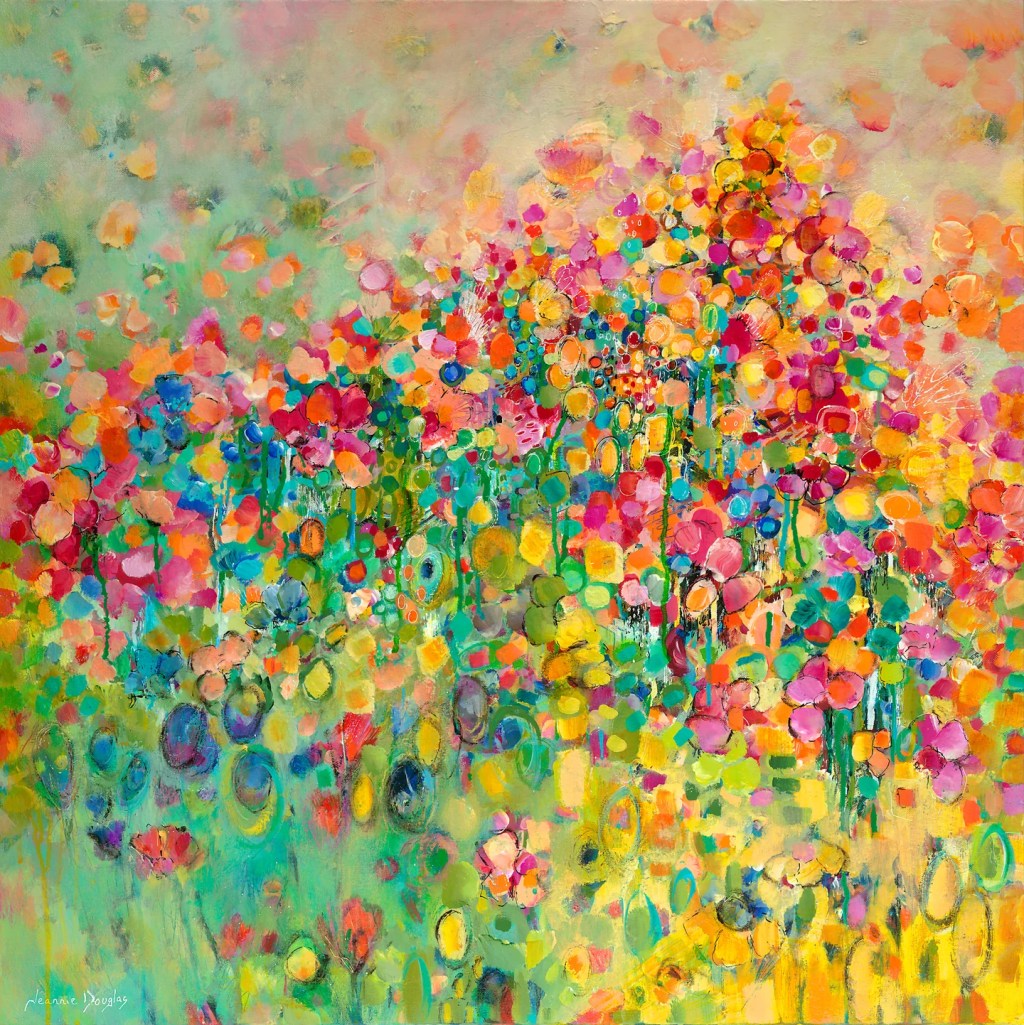

Mohul Bhowmick browses on the past and the present of Hyderabad in a nostalgic tone capturing images with words. From the distant shores of New Zealand, Keith Lyons takes on a more individualistic note to muse on the year as it affected him. Meredith Stephens has written of her sailing adventure and life in South Australia. Devraj Singh Kalsi describes a writerly journey in a wry tone. Rhys Hughes also takes a tone of dry humour as he continues with his poems musing on photographs of strangely worded signboards. Colours are brought into poetry by Michael R Burch, Farah Sheikh, George Freek, Rajiv Borra, Kelsey Walker, John Grey, Stuart McFarlane, Saranyan BV, Ryan Quinn Falangan and many more. Some lines from this issue’s poetry selection by young Aman Alam really resonated well with the tone defined by the contributors of this issue:

It's always the common people who pay first.

They don’t write the speeches or sign the orders.

But when the dust rises, they’re the ones buried under...

— Whose Life? By Aman Alam

Echoing the theme of the state of the common people is a powerful poem by Manish Ghatak translated from Bengali by Indrayudh Sinha, a poem that echoes how some flirt with danger on a daily basis for ‘Fire is their life’. Professor Alam has brought to us a Bengali poem by Jibanananda Das that reflects the issues we are all facing in today’s world, a poem that remains relevant even in the next century, Andhar Dekhecche, Tobu Ache (I have seen the dark and yet there is another). Fazal Baloch has translated contemporary poet Manzur Bismil’s poem from Balochi on the suffering caused by decisions made by those in power. Ihlwha Choi on the other hand has shared his own lines in English from his Korean poem about his journey back from Santiniketan, in which he claims to pack “all my lingering regrets carefully into my backpack”. And yet from the founder of Santiniketan, we have a translated poem that is not only relevant but also disturbing in its description of the current reality: “…Conflicts are born of self-interest./ Wars are fought to satiate greed…”. Tagore’s Shotabdir Surjo (The Century’s Sun, 1901) recounts the horrors of history…The poem brings to mind Edvard Munch’s disturbing painting of “The Scream” (1893). Does what was true more than hundred years ago, still hold?

Reflecting on eternal human foibles, Naramsetti Umamaheswararao creates a contemporary fable in fiction while Snigdha Agrawal reflects on attitudes towards aging. Paul Mirabile weaves an interesting story around guilt and crime. Sengupta takes us back to her theme of artistes moving away from the genre, when she interviews award winning actress, Divya Dutta, for not her acting but her literary endeavours — two memoirs — Me and Ma and Stars in the Sky. The other interviewee Lara Gelya from Ukraine, also discusses her memoir, Camels from Kyzylkum, a book that traces her journey from the desert of Kyzylkum to USA through various countries. In our book excerpts, we have one that resonates with immigrant lores as writer VS Naipual’s sister, Savi Naipaul Akal, discusses how their family emigrated to Trinidad in The Naipauls of Nepaul Street. The other excerpt from Thomas Bell’s Human Nature: A Walking History of the Himalayan Landscape seeks “to understand the relationship between communities and their environment.” He moves through the landscapes of Nepal to connect readers to people in Himalayan villages.

The reviews in this issue travel through cultures and time with Somdatta Mandal’s discussion of Kusum Khemani’s Lavanyadevi, translated from Hindi by Banibrata Mahanta. Aditi Yadav travels to Japan with Nanako Hanada’s The Bookshop Woman, translated from Japanese by Cat Anderson. Jagari Mukherjee writes on the poems of Kiriti Sengupta in Oneness and Bhaskar Parichha reviews a book steeped in history and the life of a brave and daring woman, a memoir by Noor Jahan Bose, Daughter of The Agunmukha: A Bangla Life, translated from Bengali by Rebecca Whittington.

We have more content than mentioned here. Please do pause by our content’s page to savour our December Issue. We are eternally grateful to you, dear readers, for making our journey worthwhile.

Huge thanks to all our contributors for making this issue come alive with their vibrant work. Huge thanks to the team at Borderless for their unflinching support and to Sohana Manzoor for sharing her iconic paintings that give our journal a distinctive flavour.

With the hope of healing with love and compassion, let us dream of a world in peace.

Best wishes for the start of the next year,

Mitali Chakravarty

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose-garden.

TS Eliot, ‘Burnt Norton’, Four Quartets (1941)

Click here to access the content’s page for the December 2024 Issue

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.