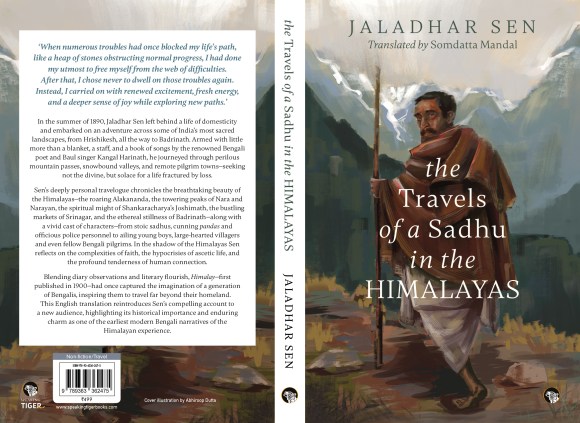

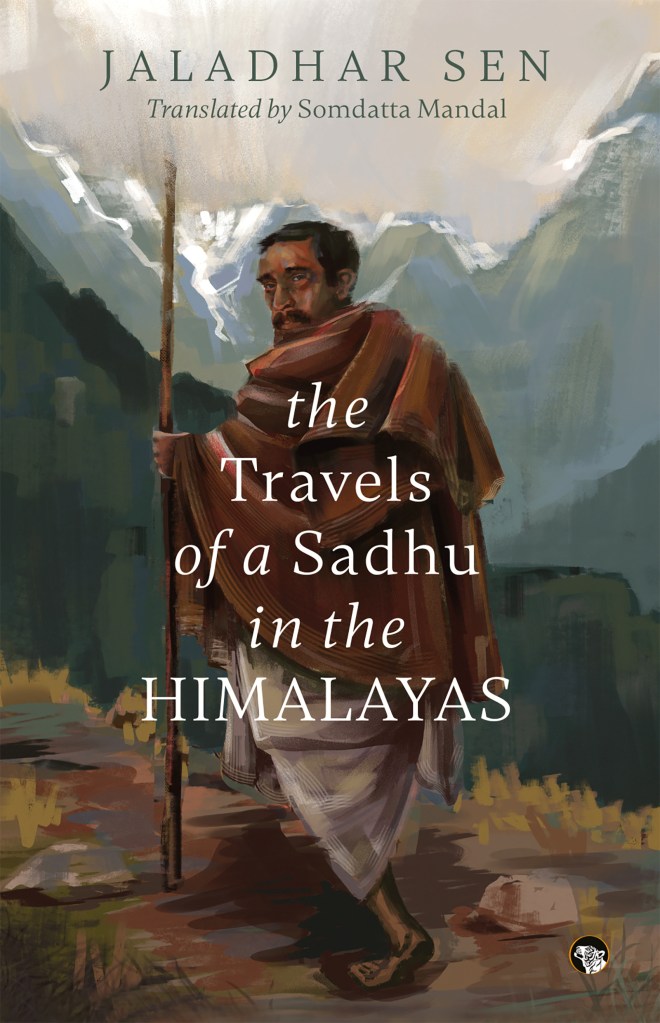

A review of Jaladhar Sen’s The Travels of a Sadhu in the Himalayas, translated from Bengali by Somdatta Mandal, published by Speaking Tiger Books, and a conversation with the translator.

Jaladhar Sen (1860–1939) travelled to the Himalayas on foot with two sadhus[1] in quest of something intangible. His memoir makes us wonder if it was resilience, for after all he lost his daughter, wife and mother — all within a few months. He moved to Dehradun from Bengal for a change of scene after his tragic losses before journeying into the hills.

Written in Bengali and first published as a serial in the Tagore family journal, Bharati, in 1893, the book was brought out in 1900 as Himalay. It has been brought to Anglophone readers by Somdatta Mandal, an eminent translator who has extensively translated much of Tagore’s essays and journals. She is a critic and scholar, a former professor of Santiniketan, an excellent translator to bring Jaladhar Sen’s diary to light. Mandal has given a lucid and informative introduction to Sen, his book and her translation — very readable and without the use of scholastic language or words which would confuse readers. Her commentary adds value to the text by contextualising the people, the times and the circumstances.

Her translation is evocative of the journey, creating vivid visual impact with the play of words. Sen is a Bengali who has picked up Hindi during his brief stay in Dehradun. That he uses multiple vernaculars to move around with two more Bengali migrants who have turned to a religious life and meets locals and pilgrims from a variety of places is well-expressed with a smattering of expressions from various languages and dialects. Mandal has integrated the meanings of these words into the text, making it easy for readers unfamiliar with these phrases to read and enjoy the narrative without breaking the continuity.

Sen is secular and educated — not ritualistic but pragmatic. You can see his attitudes illustrated in an incident at the start of the book: “We quickened our pace, but when we caught up to the two sanyasis, I felt a mix of amusement and irritation. One of them turned out to be my former servant, whom I had dismissed twenty or twenty-five days earlier for theft. His transformation was remarkable—dressed in the elaborate robes of a sanyasi, with tangled hair and constant chants of ‘Har Har Bom Bom’, he was barely recognisable as the thief he once was. It was sheer bad luck on his part that our paths crossed that day.”

At the end of the journey too, Sen concludes from his various amusing and a few alarming experiences: “Many imposters masquerading as holy sanyasis brought disgrace to the very essence of renunciation. Most of these so-called sanyasis were addicted to ganja[2], begged for sustenance, and carried the weight of their sins from one pilgrimage site to another.”

Yet, there is compassion in his heart as the trio, of which Sen was a part, help a sick young youth and others in need. He makes observations which touch ones heart as he journeys on the difficult hilly terrain, often victimised by merciless thunderstorms, heavy downpours and slippery ice. He writes very simply on devotion of another: “I felt happy observing how deep faith and belief illuminated his face.” And also observes with regret: “We have lost that simple faith, and with it, we have also lost peace of mind.” He uses tongue-in-cheek humour to make observations on beliefs that seem illogical. “In such matters, credit must be given to the authors of the Puranas. For instance, Hanuman had to be portrayed as colossal, so the sun was described as being subservient to him. However, with the advancement of science, the estimated size of the sun grew larger, and instead of diminishing Hanuman’s glory, his stature had to be exaggerated even further. Similarly, Kumbhakarna’s nostrils had to be depicted as enormous, so that with each breath, twenty to twenty-five demon monkeys could enter his stomach and exit again.”

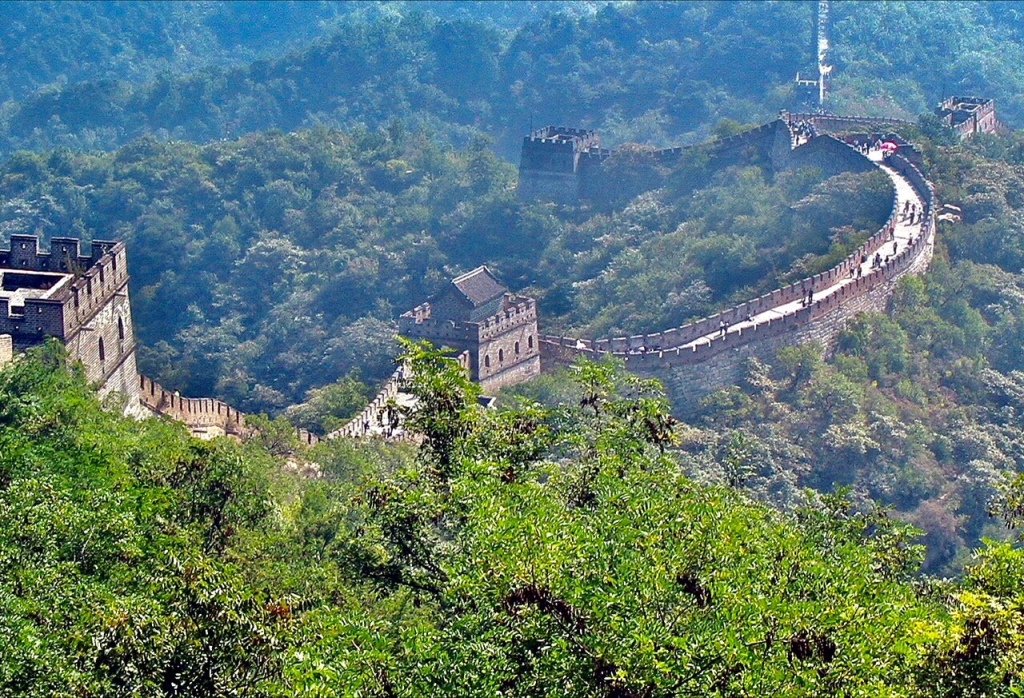

Mandal has translated beautiful descriptions of the Himalayas from his narrative with lucid simplicity and elegance. When Sen chances to see the first snow peaks, the wonder of it, is captured with skill: “We were amazed to see a huge mountain of snow, its four large peaks encircling us. The sun was already quite high in the sky, and its bright rays fell upon those mountain peaks, radiating hues that cannot simply be described in words. Even the best painter in the world could not replicate the scene with his brush.” And: “Yet the scenery that unfolded before my eyes was simply magical. Standing in front of this pristine beauty, man’s power and pride were humbled. He could recognise his own triviality and weakness very clearly and, to a certain extent, grasp the greatness of the creator within his heart.”

And of course, there is the typical Bengali witty, sardonic banter creeping in to the narrative: “On certain days, when I felt inclined to indulge in minor luxuries, I would purchase a few pedas. However, such bravado was rarely worth the effort, as one might have needed the assistance of archaeological experts to determine the sweets’ actual date of origin—no one could tell how many generations of worms had made their home inside them!”

The translation has retained the simplicity of the narrative which Sen tells us was essentially his style. He had no intention of publishing what he wrote. He had started out in company of a sadhu with a staff, a blanket and a stock of Baul Kangal Harinath’s songs. He writes at the end: “I didn’t intend to write a diary. I had a songbook with me, and when that book was being bound, I had added a few blank pages with the idea of writing down new songs if I came across them.” He scribbled his notes in those blank pages.

The journey makes a wonderful read with its humorous descriptions of errant sadhus, frightening storms, descriptions of geographies and travel arrangements more than a hundred years ago, where the pilgrims live in shop houses and eat meagre meals, the perseverance, the wonder, the love and friendship one meets along the way. Though there is greed, theft and embarrassment too! Some of his narrative brings to my mind Nazes Afroz’s translation of Syed Mujtaba Ali’s In a Land Far from Home: A Bengali in Afghanistan.

Mandal tells us: “A prolific writer, Sen authored about forty-two books, including novels, travelogues, works with social messages, children’s literature, and biographies.” In real life, she describes Sen as “a writer, poet, editor, philanthropist, traveller, social worker, educationist and littérateur.” That’s a long list to wear. There’s more from Mandal about what the book offers and why she translated this unique travelogue in this exclusive interview.

How did you chance upon this book and why did you decide to translate it? How long did the whole process take?

I have been writing and researching on Indian Travel Writing for almost over two decades now and so was familiar with the sub-genre of travel writing about the Himalayas. In Bangla, there exists a great number of books on travel to holy places as part of a pilgrimage from the mid-19th century onwards. But this book was unique because it was written by a secular person who did not go to the Himalayas as part of a pilgrimage but nevertheless got influenced by the other pilgrims with whom he went along. It was in the summer of 1890 when he actually travelled, and later in 1893, his perilous experience was published serially in the Bengali periodical Bharati which was then edited by Rabindranath Tagore’s niece, Sarala Devi Choudhurani.

During that period, with the proliferation of travel narratives being regularly published in several contemporary Bengali periodicals, Jadadhar Sen’s narration became very popular and after 1900 when it was published in book form, it took the Bengali readers of the time by storm. Its popularity led to it being included as part of the syllabus at Calcutta University. Feeling that pan-Indian readers who could not read the original text in Bangla should get to read this interesting text in English, I was inspired to translate this travelogue for a long time and Speaking Tiger Books readily accepted my proposal a couple of years ago.

The places visited by Sen might not seem unique in the present context, but the period during which he undertook the travel and the culture-specificity of it needed special attention. I was busy editing two volumes of travel narratives to Britain then, and after I finished my project, I took up translating this text in full earnest. It took me about three months to complete the translation, and I send the manuscript to the publishers in January this year. After several editorial interventions, it ultimately saw the light of day in July 2025.

Did you need to input much research while doing the translation? How tough was it to translate the text, especially given that it has multiple language and cultural nuances?

I did have to do some biographical research on Jaladhar Sen as his narrative is absolutely silent about why he moved from Bengal to Dehradun and the actual reason for his setting out on this particular journey. Interestingly, I was also researching about Swami Ramananda Bharati, who was the first Bengali traveller to Tibet and Manas Sarovar, and who wrote the famous book Himaranya (The Forest of Snow) whom Sen knew earlier and with whom he actually undertook the journey. With several cross references I could fill in a lot of biographical gaps in the narrative.

Regarding translation, it must be kept in mind that though something is always lost in translation, one must always attempt to strike the right balance between oversimplification and over-explanation. Translation is also a sort of creativity and the challenges it poses are significant. The intricate navigation between the source language and the translated language shows that there are two major meanings of translation in South Asia – bhashantar, altering the language, and anuvad, retelling the story. Without going into major theoretical analyses that crowd translation studies per se, I feel one should have an equal grasp over both translated and source languages to make a translated piece readable.

What are the tools you have used to retain the flavour of the original narrative? Please elaborate.

Readability of this old text Himalay in the present context is of paramount importance and though it is very difficult to replicate the grandiose writing style of late nineteenth-century Bangla, I have attempted to retain as much of the original flavour of the text as possible. Without using glossary or footnotes, the meaning of certain words becomes evident through paraphrasing the text. Thus, in keeping with Jaladhar Sen’s original work, the names of some words have been retained as they are. For example, the words dharamshala and chati—resting places on the pilgrim’s path—are so culture-specific that they are retained in their original forms. Sen also uses other culture-specific words such as panda (the Brahmin middleman who acts as the intermediary for worshipping the deity), the kamandalu (the water jug carried by sanyasis), lota-kambal (the jug and blanket that emphasise one’s identity as a sadhu), the jhola (the typical cloth bag that hangs from the shoulders), and the mahanta, or the head priest of the temple. Again, different terms such as sadhu, sanyasi, and yogi are used at different points to define ascetics and are often employed interchangeably. The term math, denoting seats of authority and doctrinal learning, has also been retained in its original form. As a Bengali gentleman settled in western India— Dehradun—the author often refers to Bengal as his desh, which literally means ‘country’, but in his parlance refers to the region of Bengal, which is as much a part of India as Dehradun. This definition should not create any confusion in the reader’s mind.

You, like the author, never clearly tell us why Sen starts out on such a perilous journey. Why do you think he went to this journey?

From evidential sources we get to know that like any other domestic person Jaladhar Sen began his career as a teacher in a High School in 1883 in Faridpur in Bengal. He got married in 1885 but however, a few years later he endured a great personal tragedy, losing his family members in quick succession. In 1887, his newborn daughter died on the twelfth day after her birth, and his wife passed away another twelve days later. Within three months, his mother also died. Overwhelmed by grief and seeking solace, he moved to Dehradun at the foothills of the Himalayas, where he worked as a teacher.

It is known that Sen did not venture into the Himalayas out of wanderlust. Dejected with domestic life, he apparently went to Kumbh Mela in Haridwar, where he chanced upon Swami Ramananda Bharati, an elderly Bengali sadhu whom he had known previously. He decided to accompany him on a trek all the way to Badrinath on foot. This was the background to his Himalayan travels and how he became a paribrajak sadhu or a traveller saint. The year was 1890.

Even though the memoir spans only a month, the author underwent many changes. Would you regard this book as a bildungsroman of sorts, especially as there is a self-realisation that comes to Sen at the end? Please elaborate.

In his travel account Sen documents his experiences of journeying to various places of religious significance, namely Devaprayag, Rudraprayag, Karnaprayag, Vishnuprayag and Joshimath before reaching the temple town of Badrinath in the upper Himalayas. He undertook this journey as a secular sojourner. But the travel impacted his soul in such a way that at the end of his narrative he admits that he had ventured in the Himalayas with a funeral pyre burning within his heart; and he merely embraced the cool breeze of the mountains with his hands and pressed the hard snow against his chest. He is doubtful whether he had the time or the state of mind to witness the eternal glory of the Lord revealed in the heavenly scenes around him. Could he lift his head and look towards heaven? That sense of wonder was absent within him. But some sort of change had already appeared within him. In this context, I feel the last two sentences of his narrative to be very significant when he states: “If anyone feels inspired to visit the Himalayas after reading this simple travel narrative of mine, then all my writing will have been worthwhile. And if anyone journeys towards the feet of the god of the Himalayas, my life would have been fulfilled.”

What was your favourite part of the book. Did you enjoy translating some things over others? Please elaborate.

There are several sections in the book which I really enjoyed translating. Most of them relate to specific incidents that Sen encountered during his travels and how human nature was the same everywhere. The first one was when they were on their way to Devaprayag and in his diary entry on 11th May, he tells us about the incident when his money pouch along with the Swamiji’s tiger skin was stolen on the way and how with the help of a panda he managed to retrieve it after a lot of effort. Though they were not very much spiritually inclined, they realized that there were crooks on the way to the pilgrimage sites who also dressed up as sadhus and everyone could not be trusted in good faith.

The second memorable incident is when trekking during extremely inclement weather — rain and thunderstorm– and when stones rushed down from the mountain slopes nearly killed them, how Achyutananda or Vaidantik who was accompanying them managed to protect him by shielding from the natural calamities with his own body as a mother hen does to protect her chicks.

The third interesting incident that Sen narrates is dated 3rd June when they got stranded at a chati in Pipul Kuthi. The head constable or jamadar sahib arrived there to enquire about a theft and Sen tells us how even in that remote mountainous region, the police had the reputation for rudeness and stern behaviour as the Bengal police had. He writes, “These officers, tasked with restraining wrongdoers and protecting civil society, displayed the same demeanour no matter where they were stationed. It seemed that the police were the same everywhere.”

Another memorable section is when they chance upon a young boy who probably ran away from his house and was trekking with them for some part of the way. The way in which the sick lad was ultimately deposited under the care of a doctor in the local hospital is extremely moving. Several other sections can also be mentioned here but it will turn my reply excessively long.

Why did you feel the need to bring this book to a wider readership? Are you translating more of his books?

I have already mentioned the importance of Sen’s travelogue in charting the long tradition and rich repertoire of Bengali travel narratives on the Himalayas that focus on travel as pilgrimage. As early as 1853, Jadunath Sarbadhikari embarked on a journey from a small village in Bengal to visit the sacred shrines of Kedarnath and Badrinath. Returning in 1857, he chronicled his travels in Tirtha Bhraman (1865). Two lesser-known pilgrimages to the Himalayas were undertaken by monks of the Ramkrishna Mission order – Swami Akhandananda and Swami Apurvananda—in 1887 and 1939, respectively. Their travelogues were published many years later by Udbodhan Karyalaya, the official mouthpiece of the Mission. In both narratives, we find vivid details of the hardships of travelling during that period, marked by limited financial resources and minimal material comforts.

Jaladhar Sen’s narrative also holds a significant position in this chronological trend of writing about travelling in the Himalayas. From the 1960s onwards we find a proliferation of Himalayan travel writing in Bangla by writers such as Prabodh Kumar Sanyal, Shonku Maharaj, Umaprasad Mukhopadhyay and others, and many of these texts need to be translated provided one finds a responsive publisher for them. I am not translating Jaladhar Sen anymore, though as a prolific writer Sen authored about forty-two books, including novels, travelogues, works with social messages, children’s literature, and biographies.

How do you choose which text to translate? You always seem focussed on writers who lived a couple of centuries ago. Why do you not translate modern writers?

There is no hard and fast rule for selecting which text I want to translate. I have already translated several travel texts by Bengali women beginning from Krishnabhabini Das’s A Bengali Lady in England, 1876, to later ones. But I have not translated any travelogue about the Himalayas before. Here I must be candid about two issues. I pick upon writers usually whose texts are free of copyright as that does not entail a lot of extra work securing permissions etc. The second more practical reason is that I still have a long bucket list of translations I would like to do provided I find an agreeing publisher. But that is very difficult because several of my proposals have been rejected by publishing houses because they feel it will not be marketable in the current scenario.

As for the query about translating modern writers let me narrate a particular incident. As a woman writer and as someone interested in translating travel narratives of all kinds, I had approached Nabanita Dev Sen through a willing publisher to translate her visit to the Kumbh Mela that she wrote about in her book titled Koruna Tomar Kone Poth Diye[3]. After seeking necessary permission and meeting her personally on several occasions to discuss several chapters, I gradually got frustrated because even after three sets of corrections, the translation did not satisfy her.

She consulted several other people, including her own daughter, and ultimately told me that she couldn’t accept my translation because she ‘didn’t find herself in it.’ The colloquial Bangla humour in some places were not sufficiently translated. As far as I got to know from the publisher, she changed editors thrice, and in the end the translated book was published with one of the editors named as the ‘translator’. When I chanced to meet her at my university on a different occasion, Nabaneetadi told me that she had mentioned my name in the acknowledgement section of the book, which of course I didn’t bother to buy or check. From such a bitter experience, I feel staying with writers dead long ago is a safer bet for me.

You are working on a new translation. Will you tell us a bit about your forthcoming book?

As I have already mentioned, I found Swami Ramananda Bharati’s Himaranya (The Forest of Snow) to be a companion piece for translation. Not only is this significant because it was the same Swamiji with whom Jaladhar Sen travelled to the Himalayas, and though his name is not mentioned anywhere by Sen, we get to know a lot about him already through his narrative. As a monk, Bharati travelled to Mount Kailash and Manas Sarovar in Tibet during 1898, the first Bengali to do so. These travels form the basis of Himaranya. It was not entirely ‘spiritual’ or ‘theological’ but rather depended on the traveller’s own temperament. There are presentations of secular interests and considerations, and modern readers can relate to them easily, especially because the route to Kailash and Manas Sarovar has now been opened for Indian pilgrims once again and several groups are going there every other day. The manuscript is already with the publisher and hopefully the book should see the light of day by the end of this year if everything goes well.

You have translated so many voyages by Tagore, by Sen, do you now want to bring out your own travelogues or memoirs?

I have been translating travel narratives of different kinds for a long time now. I still plan to do a few more if I get a proper publisher for the same. I am an avid traveller myself and have actually trekked to Kedarnath, Badrinath, Gangotri and Yamunotri twice. I have also trekked for fourteen days to visit Muktinath in Nepal way back in the early 1980s, and during the pandemic days when I was confined at home, I managed to key in that experience in Bangla from the diary I kept at that time. That narrative was published in the online journal Parabaas which is published from the United States. But I have never taken writing about my own travelogues or memoirs seriously. Of course, last year and also forthcoming this year, a special Puja Festive number of a Bengali magazine has been publishing my travel articles. But there is nothing serious or academic about it.

Do you have any advice for fledging writers or translators?

Translating has caught up in a big way over the past five or six years. Now big publishing houses are venturing into publishing from regional bhasha literatures into English and so the possibilities are endless. Now every other day we come across new titles which are translations of regional novels or short stories. My only advice for young writers or translators is that since copyright permissions have become quite rigid and complicated nowadays, it is always advisable to seek permission from the respective authorities before venturing into translating anything. I was quite young and naïve earlier and just translated things I liked without seeking prior approval and as usual those works never saw the light of day. Also, as time went by, I learnt that translating should have as its prime motive current readability and not always rigidly adhering to being very particular about remaining close to each individual line of the source text. The target readership should also be kept in mind and so the choice of words used and glossary should be eliminated or kept to a minimum. The meaning of a foreign word should as far as possible be embedded within the text itself. All these issues would definitely make translating an enjoyable experience.

Thanks for the wonderful translation and your time.

[1] Mendicants. Sadhu and swami also have the same meaning

[2] Marijuana

[3] Translates from Bengali to The Path to Compassion, published in 1978. The translation was published by Supernova Publishers in 2012 as The Holy Trail: A Pilgrims Plight. Soma Das is mentioned as the translator.

(This review and online interview is by Mitali Chakravarty)

Click here to read an excerpt from Somdatta Mandal’s translation of Jaladhar Sen’s Travels

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International