On August 8th 2021, the chief of the International Olympic Committee, Thomas Bach, pointed out during the closing ceremony that these games were “unprecedented” and brought messages of “hope, solidarity and peace” into a world torn with the desolation generated by the pandemic. It was a victory of the human spirit again, a precursor of what is to come. That the Japanese could get over their pandemic wrought hurdles, just as they did post the nuclear disasters wrought by the Second World War and by the 2011 earthquake-tsunami at Fukushimaya, to host something as spectacular and inspiring as these international games reflects, as the commentators contended, a spirit of ‘harmony and humility’. The last song performed by many youngsters seemed to dwell on stars in the sky — not only were the athletes and organisers the stars but this also reminded of unexplored frontiers that beckon mankind, the space.What a wonderful thing it was to see people give their best and unite under the banner of sports to bring messages of survival and glimpses of a future we can all share as human beings! Our way of doing things might have to evolve but we will always move forward as a species to thrive and expand beyond the known frontiers.

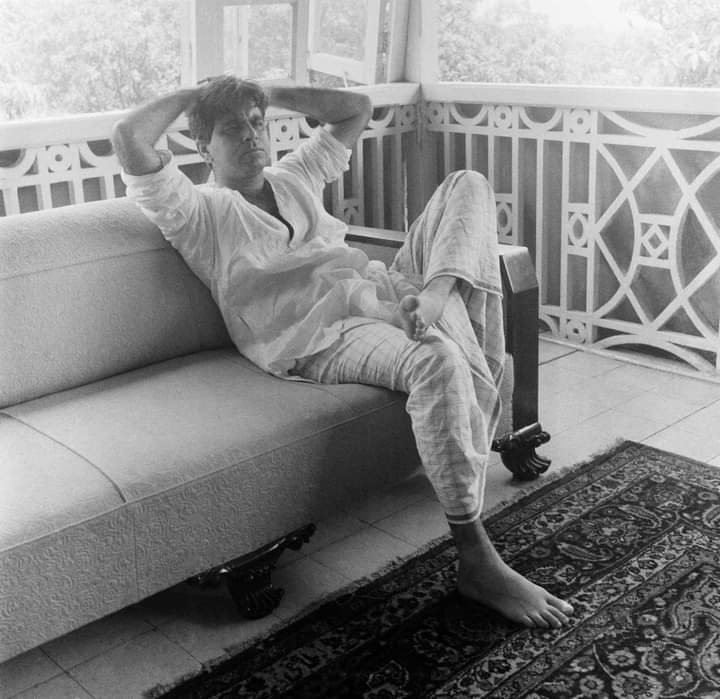

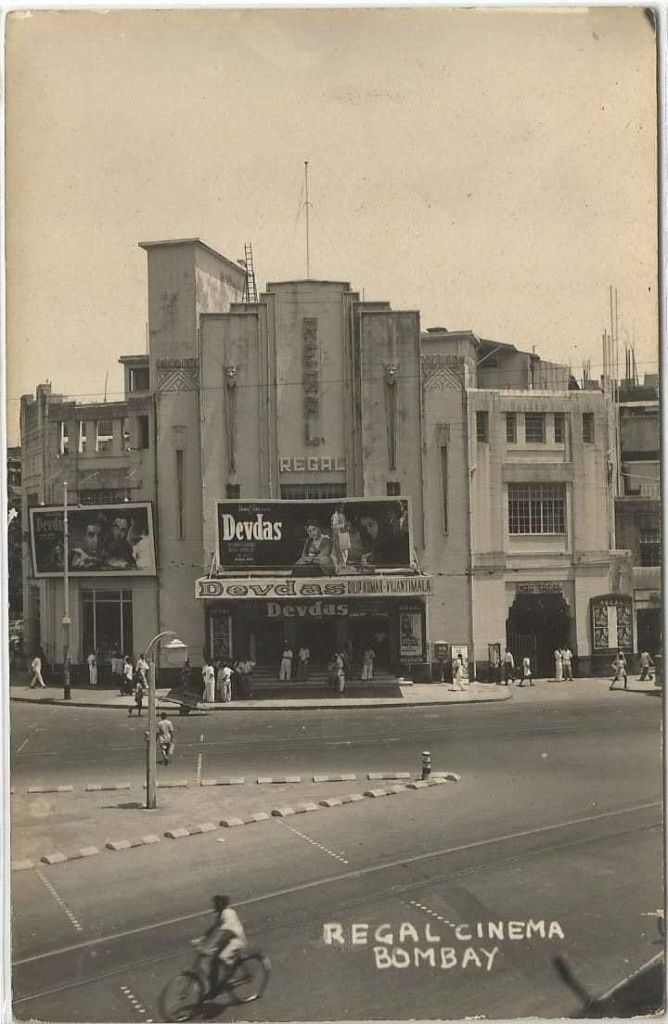

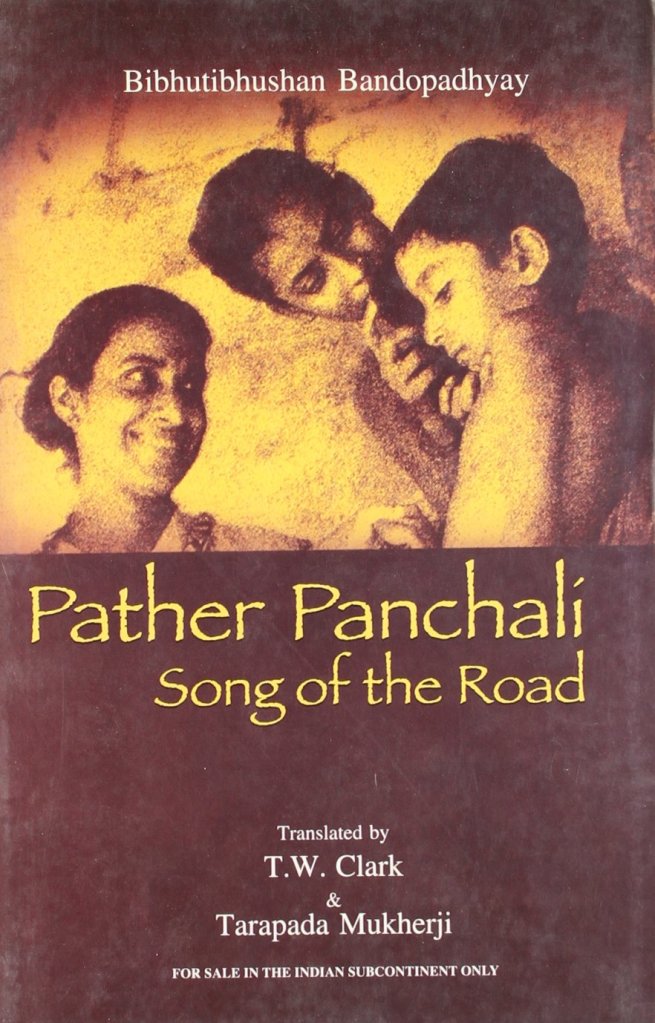

One such explorer of yet unknown frontiers who mingles the historic with the contemporary, Goutam Ghose, an award-winning filmmaker and writer, has honoured our pages with an extensive interview showing us how art and harmony can weave lores that can help mankind survive. This is reinforced by the other interview with Singaporean academic, Dr Kirpal Singh, whose poetry reflects his convictions of a better world. With our intelligence, we can redefine processes that hold us back and grind our spirits to dust — be it the conventional ‘isms’ or norms that restrict our movement forward – just as Tagore says in the poem, we have translated this time, ‘Deliverance’.

…On this auspicious dawn, Let us hold our heads high in the infinite sky Amidst the light of bounteousness and the heady breeze of freedom.

As the Kobiguru mentioned earlier in the poem, the factors that oppress could be societal, political, or economic. Could they perhaps even be the fetters put on us by the prescribed preconceived definition of manmade concepts like ‘freedom’ itself? Freedom can be interpreted differently by multiple voices.

This month, on our pages, ‘freedom’ has found multiple interpretations in myriad of ways — each voice visualising a different dream; each dream adding value to the idea of human progress. We have discussions and stories on freedom from Nigeria, Argentina, India, Pakistan, Myanmar, Malaysia and more. Strangely enough, August holds multiple independence/ national days that are always for some reason seen as days of being ‘freed’ by many — at least from oppression. But is that true?

From Malaysia, Julian Matthews and Malachi Edwin Vethamani cry out against societal, religious and political bindings – quite a powerful outcry at that with a story and poems. Akbar Barakzai continues his quest with three poems around ideas of freedom translated from Balochi by Fazal Baloch. Jaydeep Sarangi and Joan Mcnerny pick up these reverberations of freedom, each defining it in different ways through poetry.

Jared Carter takes us back to his childhood with nostalgic verses. Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Michael Lee Johnson, Vandana Sharma and many more sing to us with their lines. Rhys Hughes has of course humour in verse that makes us smile as does Jay Nicholls who continues with her story-poems on Pirate Blacktarn – fabulous pieces all of them. The sport of hummingbirds and cats among jacaranda trees is caught in words and photographs by Penny Wilkes in her Nature’s Musings. A poetic tribute to Danish Siddiqui by young Sutputra Radheye rings with admiration for the Pulitzer prize-winning photographer who met his untimely end last month on 16th while at work in Afghanistan, covering a skirmish between Taliban and Afghanistan security forces. John Linwood Grant takes up interesting issues in his poetry which brings me back to ‘freedom’ from colonial regimes, perhaps one of the most popular themes for writers.

Indo-Pak independence, celebrated now on 14th (Pakistan) and 15th August (India), reflects not only the violence of the Partition which dislocated and killed millions historically but also the trauma caused by the event. Capturing this trauma is a short story based on memories of Partition by Nadir Ali, translated from Punjabi by his daughter, Amna Ali. Ratnottama Sengupta translates from the diary of Sandhya Sinha (1928-2016), a woman’s voice from the past that empathises with the subjugated who were subdued yet again after an upsurge of violence during the Quit India Movement (1942) against the colonials. Sinha contends that though the movement frittered away, the colonials were left with an after-taste of people hankering for self-rule. A thought-provoking short story by Sunil Sharma explores the results of self-rule in independent India.

Alluding to Jinnah’s vision for women, Aysha Baqir muses emotionally about the goals that remain yet to be fulfilled 74 years after independence. Moazzam Sheikh’s story of immigrants explores dementia, giving us a glimpse of the lives of Asian immigrants in America, immigrants who had to find a new home despite independence. Was this the freedom they dreamt of — all those who fought against various oppressive regimes or colonialism?

Tagore’s lyrics might procure a few ideas on freedom, especially in the song that India calls its National Anthem. Anasuya Bhar assays around the history that surrounds the National Anthem of India, composed by Tagore in Bengali and translated to English by the poet himself and more recently, only by Aruna Chakravarti. We also carry Dr Chakravarti’s translation of the National Anthem in the essay. Reflecting on the politics of Partition and romance is a lighter piece by Devraj Singh Kalsi which says much. ‘Dinos in France’ by Rhys Hughes and Neil Reddick’s ‘The Coupon’ have tongue-in-cheek humour from two sides of the Atlantic.

A coming-of-age story has been translated from Nepali by Mahesh Paudyal – a story by a popular author, Dev Kumari Thapa – our first Nepali prose piece. We start a four-part travelogue by John Herlihy, a travel writer, on Myanmar, a country which has recently been much in the news with its fight for surviving with democracy taking ascendency over the pandemic and leaving the people bereft of what we take for granted.

Candice Louisa Daquin discusses a life well-lived in a thought provoking essay, in which she draws lessons from her mother as do Korean poet, Ihlwha Choi, and Argentinian writer, Marcelo Medone. Maybe, mothers and freedom draw similar emotions, of blind love and adulation. They seem to be connected in some strange way with terms like motherland and mother tongue used in common parlance.

We have two book excerpts this time: one from Beyond the Himalayas by the multi-faceted, feted and awarded filmmaker we have interviewed, Goutam Ghose, reflecting on how much effort went in to make a trip beyond boundaries drawn by what Tagore called “narrow domestic walls”. We carry a second book excerpt this time, from Jessica Muddit’s Our Home in Myanmar – Four years in Yangon. Keith Lyons has reviewed this book too. If you are interested in freedom and democracy, this sounds like a must read.

Maithreyi Karnoor’s Sylvia: Distant Avuncular Ends, is a fiction that seems to redefine norms by what Rakhi Dalal suggests in her review. Bhaskar Parichha has picked a book that many of us have been curious about, Arundhathi Subramaniam’s Women Who Wear Only Themselves. Parichha is of the opinion, “Elevated or chastised, exonerated or condemned, the perturbation unworldly women in India face is that they have never been treated as equal to men as spiritual leaders. This lack of equality finds its roots not only in sociological and cultural systems, but more particularly at the levels of consciousness upon which spirituality and attitudes are finally based.”One wonders if this is conclusive for all ‘unworldly women’ in India only or is it a worldwide phenomenon or is it true only for those who are tied to a particular ethos within the geographical concept of India? The book reviewed by Meenakshi Malhotra, Somdatta Mandal’s The Last Days of Rabindranath Tagore in Memoirs, dwells on the fierce independence of the early twentieth century women caregivers of the maestro from Bengal. These women did not look for approval or acceptance but made their own rules as did Jnadanandini, Tagore’s sister-in-law. Bhaskar Parichha has also added to our Tagore lore with his essay on Tagore in Odisha.

As usual, we have given you a peek into some of our content. There is more, which we leave for our wonderful readers to uncover. We thank all the readers, our fantastic contributors and the outstanding Borderless team that helps the journal thrive drawing in the best of writers.

I wish you all a happy August as many of the countries try to move towards a new normal.

Mitali Chakravarty