By Meredith Stephens

“This is just like Midsomer Murders without the murders!” I quipped to Alex.

Midsomer Murders was one of my favourite British crime shows. In particular, I loved the depiction of English village life, where villagers gossiped on the village green. The only problem was when the happy village life was interrupted by a gruesome and unexpected murder. Then I had to place my hands before my eyes to block out the scene of the murder in case the camera lingered there too long.

Alex, Verity and I were visiting the Mypunga Markets in the South Australian countryside. The first vendor was selling a wide selection of eye-wateringly delectable Greek cakes. To our right was an Italian wine-grower selling his wines, such as Pinot Grigio, from a nearby vineyard. A Korean stall holder was selling kimchi[1]. Perhaps the offerings were a tad more multicultural that those depicted on the village green in Midsomer Murders. Farmers sold organic vegetables and local dairies sold cheeses. We stopped to soak in the sounds of a group of elderly ukulele players. Shoppers were wearing home-spun hand-knitted jumpers, scarves and beanies, carrying shopping bags made of cheesecloth. I revelled at being on the set of the South Australian equivalent of the village green in Midsomer.

Our purpose for driving into the countryside was twofold. After the market, we went to the shed at Alex’s hobby farm to collect some firewood. Alex unlocked the gates at the roadside entrance, and we drove through the spotted eucalypts, wound up and down the hill through the gorge to eventually arrive at the shed. The roller door was wide open. This was the first time we had been greeted by an open roller door. We parked and peeked inside.

“Don’t go in, Dad!” screamed Verity.

Plastic tubs had their lids off. Children’s toys were scattered. Furniture was tipped over. The new off-grid battery modules, in the process of being installed, had been ripped out and strewn on the floor. We could not turn on the lights because they were powered by the batteries.

We carefully continued our entry into the huge dark shed lest we surprise the burglars and become a victim ourselves. No-one was there. I looked in the ancient sideboard I had inherited from my grandmother and opened the top drawers. My forty-year-old flutes were missing. Were the burglars flautists?

We righted the upturned furniture, returned the toys to the plastic tubs, affixed the lids and stacked them neatly. Then Alex got on the phone to his young employee, Troy.

“Would you mind getting hold of a battery-powered camera and placing it up high in the gum tree facing the shed door?” he asked. “We need surveillance.”

It was Saturday and Troy’s day off, but he was willing to assist Alex, and by 9 pm that evening he had purchased a camera and placed it where requested. He used the drop-down menu to ensure that notifications of camera images would come to his phone.

We returned home with the firewood. At least the burglars hadn’t stolen that. We lit a fire in the fireplace and luxuriated in front of it, savouring the delights we had purchased at the Mypunga markets. Now we had a camera installed, surely, we would be safe.

At 5 am the next morning the telephone rang. It was Troy. Alex’ phone had been on bedtime mode, and he could not have received calls any earlier.

“They’ve broken in again,” said Troy. “At 2.38 am. This time with a car. The footage came to my phone.”

“Are you there now?” asked Alex.

“Yes. I came straight here when I got the notification.”

“OK. We’ll head over there this morning. Have you called the police?”

“Yes. They’re coming shortly.”

Usually, I savour sleeping in on the weekend, or in fact on any day, but suddenly I had no desire to continue nestling between the brushed cotton sheets. I had been jolted awake.

“Are we going now?” I asked Alex.

“Soon. I have to wait for the hardware store to open. I want to buy some metal reinforcements to secure the shed door. Because we have no power, I’ll have to buy an inverter to power my tools.”

We drove towards Mypunga, first stopping at the hardware store en route to buy the bolts and then at an electronic’s store to buy the inverter. When we arrived at the farm we stopped at the gates to check the locks. The chain had been cut with bolt cutters. Then came a phone call from Troy.

“Are the police here?” asked Alex.

“Yes. They have collected fingerprints and DNA samples. They are coming out now to talk to you.”

Soon we were joined at the gates by four detectives and Troy. It was 11 am. Troy had been on the site for at least six hours, not to mention having been there at 9 pm the night before to install the cameras. He excused himself and the detectives explained to Alex the evidence they had found. The visit from the previous day had been a stake-out on foot. Once they had discovered the batteries, they had resolved to return with a car. The batteries were too heavy to have been carried out on foot. But not the flutes. They were much lighter than the batteries.

The police promised to examine the footage carefully. It captured the arrival of the car, and three men with torches circling the shed. One of the men had spied the camera, seized it, and thrown it down the hill. After that the images from the camera were of the surrounding grass. The detectives left and Alex and I drove up and down the winding track to the shed. The roller door was wide open. We entered, and the carefully stacked boxes again were opened and the lids strewn around the shed. Toys and hats were scattered. The drawer from which my flutes had been removed was now firmly wedged against the sideboard. They had clearly opened and shut it again, even after having removed the flutes the day before.

Unlike in Midsomer, no-one had been murdered, but there was a strong sense of violation. Burglars had staked out Alex’s shed, upturned the contents, and left with the roller door still open. Returning the very next day after having staked out the property was brazen. There was a dark underside in this countryside location despite the peaceful scene we had observed the previous day in Mypunga, with shoppers in their home-spun hand-knitted jumpers carrying their organic produce in cheesecloth bags. Most likely the thieves were from elsewhere and had followed the battery installer’s vehicle emblazoned “Remote Power Australia”.

A few days later Alex received a call from the detectives requesting a DNA sample, in order to rule him out. Some tools in the shed had been used to remove the batteries, and they had produced a DNA sample from these. Alex agreed, and a constable arrived at the house the next day to take a swab.

“Have you made any progress on the case?” asked Alex.

“We’ve identified the car the burglars used from the footage. It’s a Ford Maverick. That narrows it down quite a bit.”

Meanwhile Alex and Troy restored the camera to the eucalyptus tree, and bought another one which they affixed it to another tree one hundred and fifty feet away. At the detective’s suggestion, the second camera was aimed at the first one. If a burglar took down the first camera they would be filmed by the second camera. Since the batteries had been stolen and there was no power in the shed, the cameras were operated by solar panels. Alex could regularly check for notifications on his phone.

Two months later Alex received a phone call from a constable with a strong northern English accent that transported you to a distant time and place. It was the kind of English you would hear on a British detective show, although not the southeastern English accent of the fictional Midsomer.

“This is Senior Constable Jane Michaels. We have found two flutes. They may be yours. Can you identify them from the photo? I took it with my bodycam.”

Alex showed me his phone. I couldn’t identify them from the photo. However, they had to be mine. Flute theft must be a much rarer crime than battery theft. More people are in need of batteries than a flute.

“If you prefer to identify them in person, I can make myself available next week,” explained the Senior Constable. “The burglars were not what you would call a musical family,” she quipped.

“I’ll give you my partner’s number so that you can contact her directly,” offered Alex.

The next Wednesday a call came from an unknown number. I let it ring out because I never answer unless I know who is calling. Then I listened to the recorded message the caller had left behind.

“It’s Senior Constable Jane Michaels from the Camden Police Station. I’m hoping you can identify those flutes. Please call me back.”

Hearing this English accent made me feel like I was on the set of Midsomer Murders. A frisson of excitement tingled up my spine. It was a warm, old-world and unpretentious accent that I associated with the north of England. (When you hear an English accent by a worker in South Australia, you may feel like you are on the set of a detective show like me, or you may assume they are in the health or policing professions because of the recruitment drives in Britain in these professions.)

“Can you come to Camden Station to identify them? We’ll be there in half an hour.”

I drove to the address she provided, entered through the imposing gates, and parked outside a giant warehouse. I entered the building and pressed a button marked ‘Property recovery’. A constable greeted me from behind a glass partition.

“What have you come to collect?” he asked.

“Two flutes.”

He looked at me quizzically. Flute theft is probably an uncommon crime.

“What?” he asked again.

“Flutes,” I repeated.

He disappeared to the room behind, and Senior Constable Jane Michaels appeared bearing the flutes in their cases. Despite her old-world accent on the phone, she was surprisingly young.

“Are these in fact yours?”

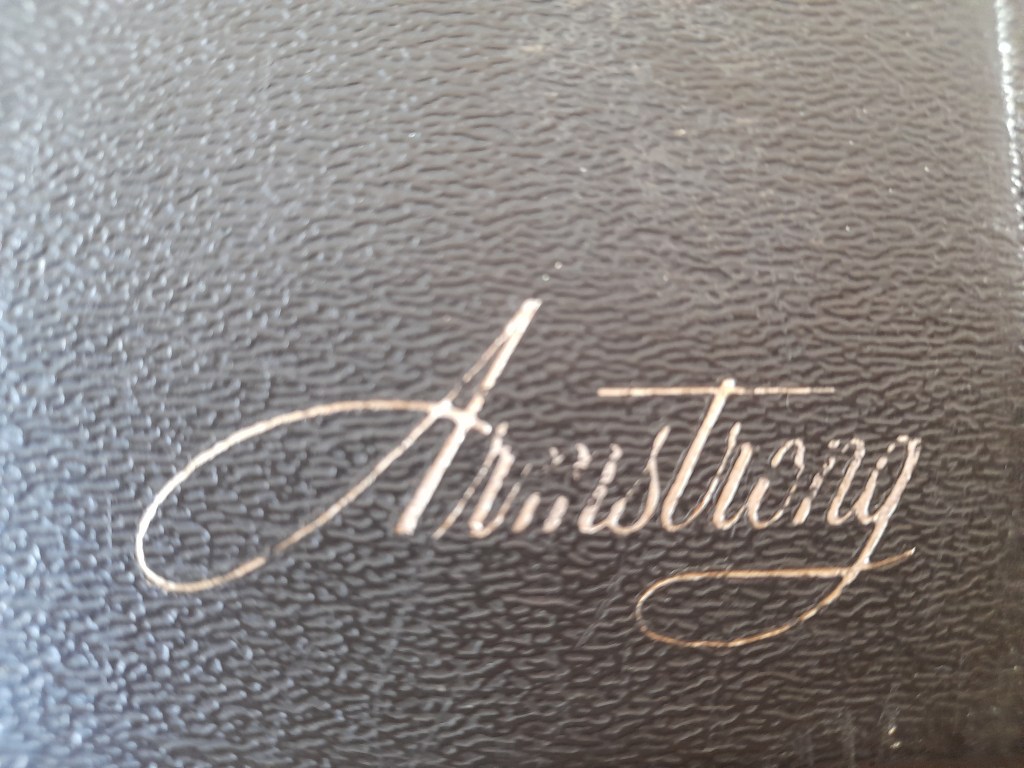

I looked at the cover of the box for the brand, and sure enough, ‘Armstrong’ was written in faded silver letters. This was the flute I had owned since my teenage years.

“How about the batteries? Are you likely to find them?” I asked hopefully.

“We didn’t find them at the property, but it’s an ongoing investigation,” she explained. I could tell from her apologetic tone that she thought we would be unlikely to retrieve them.

I thanked her and left. I returned to my car, the sole one in the enormous car park. As I drove off two constables headed to close the enormous gates behind me, smiling and waving, happy that I had been reunited with my stolen flutes.

I have to hope for Alex’ sake that the batteries will be found. Meanwhile, I haven’t played my Armstrong flute in over forty years, but now that it has been stolen and recovered in a raid, I feel compelled to take it up again. What’s more, who knows whether the recovered flutes will be instrumental in solving the crime of the stolen batteries?

[1] A spicy Korean salad

Meredith Stephens is an applied linguist from South Australia. Her recent work has appeared in Syncopation Literary Journal, Continue the Voice, Micking Owl Roost blog, The Font – A Literary Journal for Language Teachers, and Mind, Brain & Education Think Tank. In 2024, her story Safari was chosen as the Editor’s Choice for the June edition of All Your Stories.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International