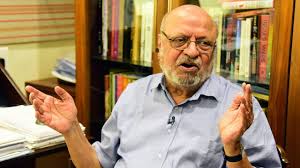

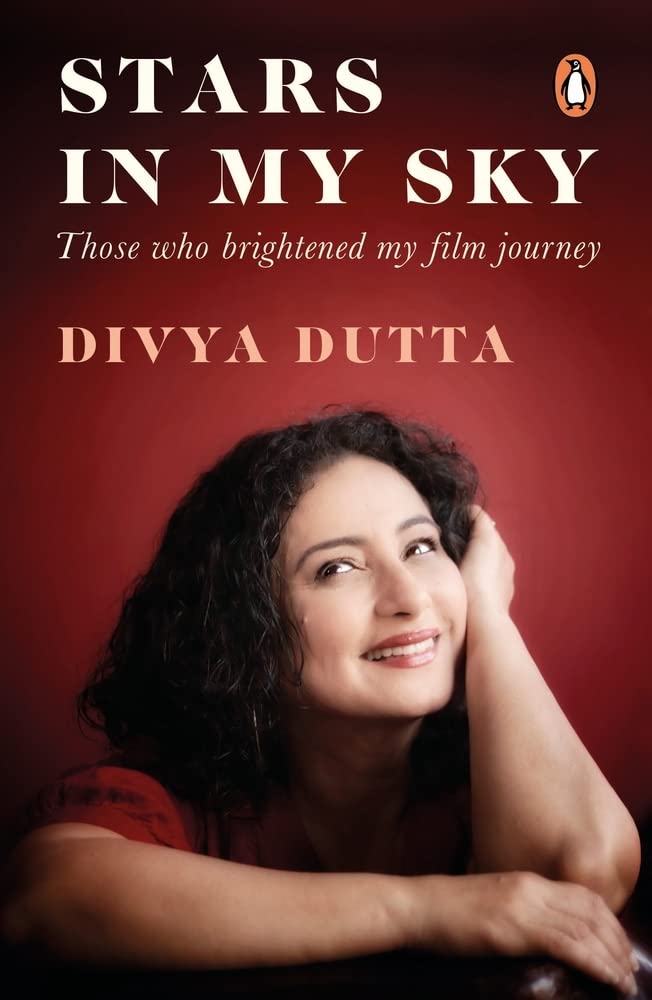

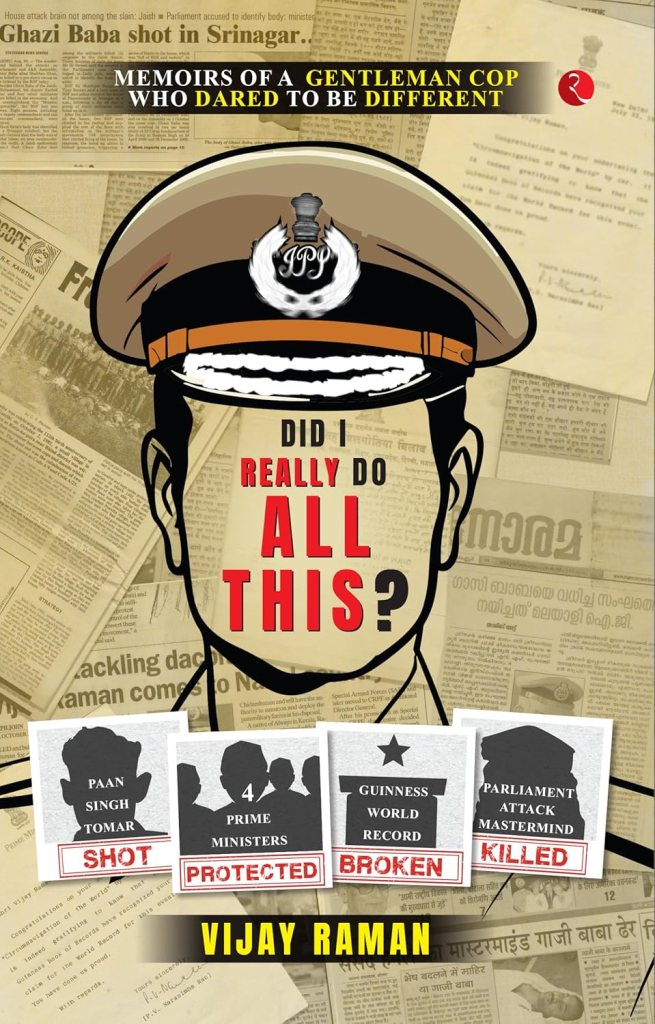

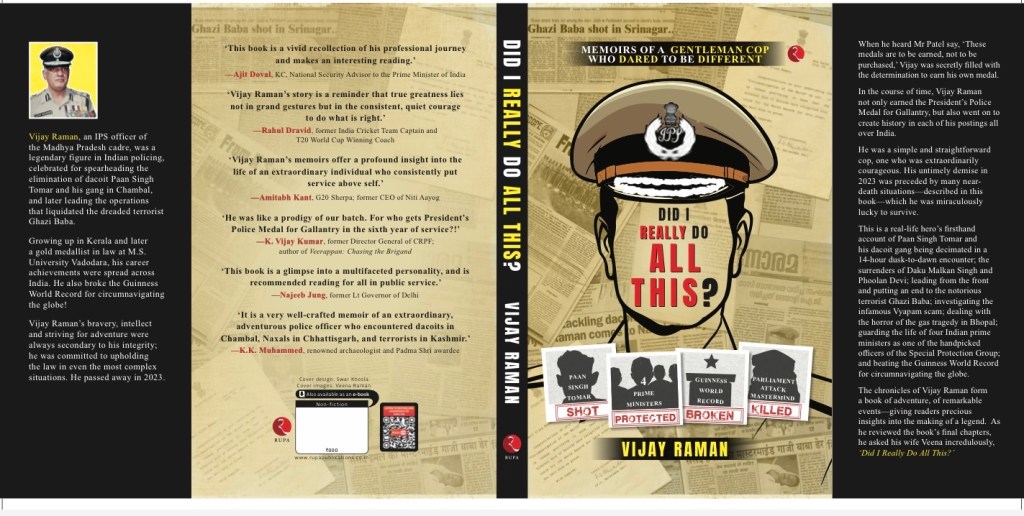

Title: Did I Really Do All This: Memoirs of a Gentleman Cop Who Dared to be Different

Author: Vijay Raman

Publisher: Rupa Publications

Bandits and a Cursed River

When I began my career in the dacoit-infested region of the Chambal Valley in Madhya Pradesh (MP), I faced different kinds of issues.

I was first posted in Dabra where there are dacoits. In such places certain people come to you offering information that will be useful to us. These are our mukhbir, informers. Some come for the pittance of money that is sanctioned to us as anti-dacoity funds for meeting emergency expenses. But most come with an ulterior motive: they want a kill. ‘We will give you information that you need and will find very hard to get without me. But you have to kill the man,’ they would say.

As ASP Dabra I had 10 police stations under me. One was at Pandokhar, a village between Jhansi and Gwalior, on the (Uttar Pradesh) UP–MP border. A very pleasant-looking chap from there would come to me, always smiling, always making conversation, inquiring about my health, telling me whatever was happening in the village. When I asked for information, he would say, ‘Saheb, sab theek hai, it’s all good, Saheb!’

I would ask if there was any news of the dacoits, and he’d say ‘No Saheb, there is no movement.’

One day he said, ‘Aaj shaam ko jayenge Saheb. We’ll go this evening.’

It was December 1978. I distinctly remember the day: India was playing Pakistan in the Asian Games hockey finals in Bangkok.

One of the problems in that area, particularly for a young newcomer, is this: Whom do you trust? Is the informer trustworthy? Is the subordinate you share the information with trustworthy? I realized that ultimately it had to be your call, based on some homework, your own observations, and your intuition.

One dictum I always followed was to stick to the informer’s plan as much as possible. Anything else would make him suspicious. So I asked him what we should do. He said that this was Devi Singh’s gang, of seven or eight people. They were going from MP to UP to conduct a burglary since it was a full moon night. They would go on bicycles—yes, the dacoits those days went around on bicycles!—and he would be with them. When we arrived at the ambush area, he would ring his bicycle bell and that would be the signal for us to spring into action. All we had to do was surround them, fire two shots into the air, and they would be ours: an easily doable plan which otherwise might be most difficult to execute!

Bidding a mildly regretful goodbye to the hockey commentary on the radio I got into my vehicle and left for Pandokhar, about 60 km from Dabra. I shared my information with the sub-inspectors and inspector in the police station there. Soon the word spread, and from their reaction I could see that this was a very dangerous gang of dacoits. There was consensus that these fellows deserved the ultimate punishment.

We walked to the location, a distance of about 10 km, and took our positions before dark. There was no way I would find out the results of the hockey match there! Sure enough, a group of cyclists arrived. Someone rang a bell. That was our signal, and we surrounded them. And that’s when some of the constables recognized him. ‘Arre! Yeh toh Devi Singh hai! And there’s a big price on his head!’

Dying Declaration

Now the drama begins for a young police officer fresh out of the academy that trains to say no third degree, no this, no that. And with just one year of service, I was still carrying the commitment to uphold the law, protect human rights, behave as the Constitution expects me to. But was it possible when facing a rebellious group of subordinates who want a kill? Before my eyes, some of them were getting ready for violence. When some senior constables and sub-inspectors pacified them they protested, ‘Why should we let them go? They are crooks, they deserve to be killed.’ We tried to convince them that we must arrest them, take them back to the police station, and let the matter be resolved in a courtroom. But that would never work, they argued, because they would bribe the authorities and get away. So they must be killed now!

After a lot of persuasion they relented. They requisitioned a bullock cart from the village, put me in it, tied the hands of the dacoits together, and tied the rope to the bullock cart so that they could not escape. And all along the way they expressed their rage by thrashing Devi Singh, a bald-headed fellow, on the head with his own chappals!

*

My mind was in turmoil. Was I doing the right thing? And why was there so much anger against him from the lower constabulary? I was on the verge of being manhandled by my constables for my stand. Luckily there were sub-inspectors who could restrain them. Was this the sense of discipline we had in the police?

Back in the police station, I phoned my senior officer, a very fine Superintendent of Police (SP) from whom I learnt many practical aspects of policing. It was nearly midnight, so I started by excusing myself for calling at that hour, but I was speaking from Pandokhar and had just returned from an encounter. He must have wondered whether this kid from the south even knew the meaning of ‘encounter’. He disconnected with instructions to see him in the morning.

I had done exactly what my informer had asked me to do—and I had arrested seven members of a gang. We had fired only two rounds of ammunition.

We sent out the required messages to all the police stations in the district, informing them that Devi Singh was in our custody, giving information about the location, number of people arrested, and other details of the encounter. And we were astonished at the large number of requests from all around asking for them to be handed over for trial.

*

The next morning I reported to my headquarters in Gwalior, met my SP, and discussed with him my thoughts and feelings about the encounter. When I told him that we must control the level of indiscipline we have in the force, the seasoned officer counselled me, ‘These are things we have to take in our stride. In the course of time you will also learn how to go about it!’

I was feeling quite pleased with myself for the excellent work done but my SP was more than a little amused. ‘Raman, you fired only two rounds! How can you have an encounter with a dacoit when the police fire only two rounds? I’m sure even the dacoits would have fired more than that. You were just very lucky that you did not get massacred. Firing two rounds is not an encounter Raman! Go and take his dying declaration, and let’s close this matter.’

I was familiar with the belief that a person on the verge of death will not lie. Therefore greater credibility is given to such a statement. Little did I know that soon this episode would come back to haunt me.

The Price of Being Idealistic

Every day we would receive the daily situation report (DSR). It mandates that events such as blind murder, unidentified dead bodies, and other serious offences must be supervised by either the SP or the ASP.

One day I received a report of the discovery of an unidentified dead body. Somehow the name of the place, which fell under the police station of Pandokhar, rang a bell, and I found myself rushing towards it with a growing sense of dread. It was about 100 km from Gwalior and by the time I got there the body, though badly mauled and with limbs dismembered, had been identified. Beside it sat a woman clutching two children tightly to herself and wailing loudly.

It was a terrible feeling to know that this was my fault. I was responsible for the death of this informer. I was the person responsible for all those who were killed by Devi Singh after his release, until he was terminated by my junior, SP Asha Gopal. It always remained on my conscience that my actions, though purely to uphold human rights and protect human life, had led to so much violence and misery.

These thoughts often disturb sensitive police officers, making them face a dilemma that nobody else can help them solve. For myself, I had resolved that following the law was not just my duty but also my dharma, righteousness. However, even in my life there would occur situations when, in the heat of the moment, it might become necessary to take decisions not in keeping with strictly legal procedures. But this would NEVER be for personal gain, and only, ONLY for the greater good.

*

People of my generation who grew up in India would have read about the dacoits and what they did. Some might have a sense of the terrain in which the Chambal dacoits lived. But today’s youngsters, especially those unfamiliar with the place and time, would not understand what it was like, or the obstacles and dangers that were involved, in policing back then.

Chambal is a large area with a peculiar topography of dunes and ravines not seen anywhere else in India. These were formed by the force of water cutting through the land. For an outsider, the area was difficult to navigate. There are settlements and villages even in the midst of the ravines, and it was impossible to know whether they were already there when the ravine formed or whether the ravine grew around them. To get from one place to another was extremely difficult for anyone unfamiliar with the area. You could get hopelessly lost, as in a maze. However, once you began to understand the geometrical pattern of the ravines, it became easier to know where to enter. Over time, the surroundings became familiar.

Other than the terrain, the people of this region were also unique. Their culture developed almost in isolation, and while they had a lot in common with people of the neighbouring areas, some of their attributes were distinctive.

They had a strong sense of justice. One that was different from what we were used to. When I studied Law, what fascinated me was understanding the causes that had given rise to a law. One of the sources of a law is the customs of the people. When a custom is predominant, the wisdom of the legislature will formulate the custom into a law that can be implemented. And some of the customs in this region are what have shaped the indigenous laws here.

Thus, people here were deeply conscious of caste; not just in terms of untouchability but also as a pecking order. While Brahmins were at the top, there were various subgroups—Sharmas and Mishras, among others—and these had their own hierarchy. This applied to how they spoke and were spoken to, or where they stood or sat in a public gathering. Indeed every social interaction was strictly dictated by caste, marriage being the most carefully monitored.

Lower castes were also kept firmly in their place. Any breach of these age-old rules was taken extremely seriously and was bound to have consequences, sometimes fatal. If a person felt aggrieved or insulted, they would hit back. But there were exceptions and unexpected alliances emerged. Notorious dacoit Maan Singh, a legend in his lifetime with a temple to his name, was from a higher caste but his gang had many dacoits from lower castes.

Secondly, women were held in the highest esteem and no misbehaviour against a woman was condoned. It may seem strange to hear that a region famous for its law-breaking dacoits could have been so particular about the safety of and respect for women, but it was so. The women were, of course, expected to behave with all propriety in order to deserve this veneration.

Next, the people in this region were very, very possessive about their land. This may well be true of everybody everywhere. But the intensity of this feeling, and the response to any infringement in this, was extreme. Any transgression would immediately be punished, and not with a simple imprisonment, because this was not a minor offence but a serious one that deserved death. And it was the same when the modesty of a woman was outraged.

Linked to all this was the prestige derived from the ownership of a licensed weapon. Whether a 12-bore gun or a weapon of any calibre, displaying it was as much a source of prestige as a row of ribbons and medals might have been to someone from the forces, or a car brand for a city dweller of today.

With this uncompromising, cast-iron value system, life was sometimes quite difficult. Let me tell you about a case that took place during my time in that area. One evening, two brothers returned home after working all day in their fields. They sat in front of their home, smoking hookahs, relaxing, waiting to be served dinner.

One brother said, ‘I’ve been wondering whether I should also buy an animal, maybe a cow or a buffalo.’

‘Oh really?’ the other replied. “And where do you plan to tie it?’

‘Right here,’ said the first brother.

‘Really?’ the second responded. ‘But this is my land! You can’t tie your cow here!’

The first brother jumped up and walked indignantly into the house. He brought out a short wooden post and a hammer, with which he hammered the post into the ground. This was the kind of post used to wind rope around and tie cattle to. With this, the first brother had established his right to tie his cow right there.

Furious, the second brother too jumped up and strode into the house. He went in, brought out his weapon, and simply shot his brother down. Such was the value of land.

In short, legality and morality have their own geographical boundaries!

*

Another incident took place some years later. By then I had some credibility with the local people.

A Dalit boy from Umri village got married. The marriage party had gone to the bride’s village and, after the wedding rituals, were bringing her home in a procession with musicians playing and people dancing. On the way they passed some Thakur homes. Some young men who sat smoking on the veranda watched with contempt and passed snide remarks. As the boy ceremoniously walked with his new bride into the house, a lewd comment was heard by all: ‘These chamars sure know how to pick their beauties!’

Loud, mocking guffaws rang out.

I should mention here that the use of the caste name ‘chamar’, with the intent to insult or humiliate is an offence today, punishable under the provisions of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

The ceremony of welcoming the bride into her new home continued with all its formality. But as soon as it was over, the groom picked up his gun, loaded it, and walked to the house where the spoilt Thakur brats still sat smoking. Taking aim, he shot and killed the boy who had made the mocking remark. In cold blood, in broad daylight. And in doing this, he was simply following the law dictated by the customs followed in this place.

For us it was a different situation altogether. The Thakurs were up in arms, the Dalit boy was absconding, and the entire chamar community had lined up, ready for a bloodbath. We had to prevent it! I spent a very tense 34 days searching for the boy in the maze-like ravines and meeting the leaders of both the communities to placate them. I was unable to sleep, constantly alert, constantly watching for any sudden movement on either side. Ultimately the boy surrendered and was sentenced.

This was the consequence of a ‘simple’ insulting comment. There is an entire framework that prescribes what the punishment should be, and in a case like this, it is different from our existing laws. Who can we blame? The people with a tradition of a certain law, or the police and the judiciary, with their own fixed sense of justice and punishment?

*

People ascribe the nature of the people and their customs to the water of the Chambal River. And having lived there I can speak for the water. It was so pure and wholesome that food got digested easily. The pulses and grains grown in the region were of the best quality. The soil was very productive, and I believe the per-acre yield was comparable to Punjab. This milieu formed the background of our police system.

Now, don’t forget that our police system was also manned mostly by people of the same area, with the same mentality and the same sense of revenge. It was a caste-based way of life. Such incidents were absolutely ‘normal’. Yet, as I soon found out, there was a great respect for authority. I was a South Indian officer without much knowledge of the place, hardly even able to speak their language. There was a lot of curiosity on both sides, but there was also respect.

Revenge on the Dead

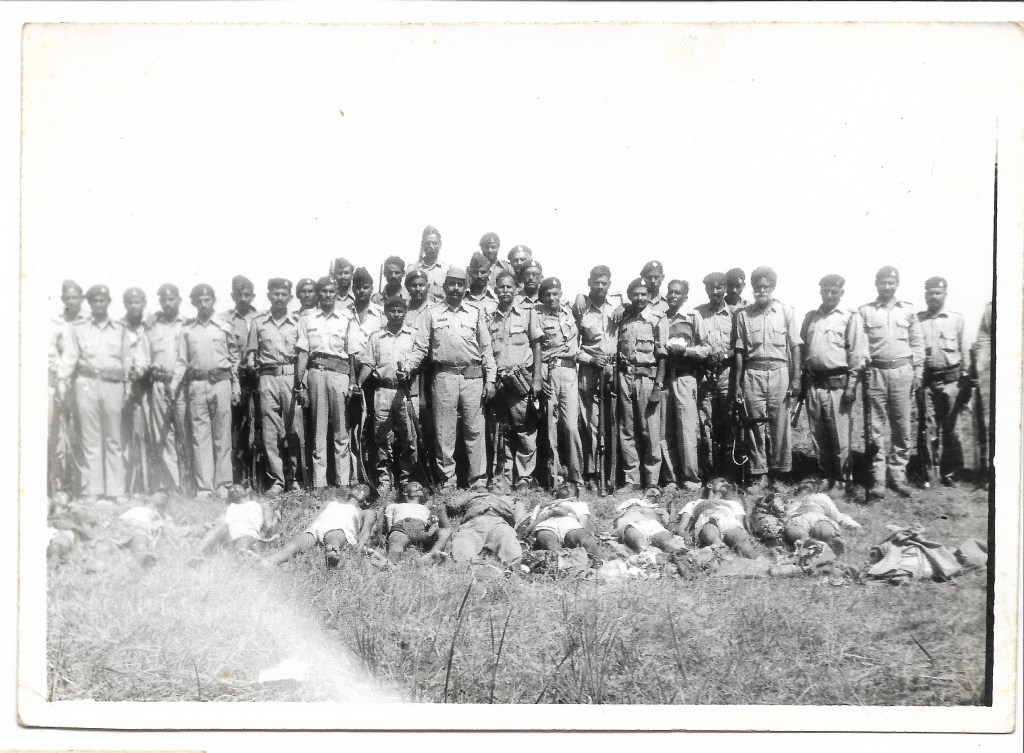

A month or two later we received information about an encounter by a local DSP, about 30 km away from Bhind, on the bank of Sindh River. Seven dacoits were killed; no names were given; it was not one of the regular gangs.

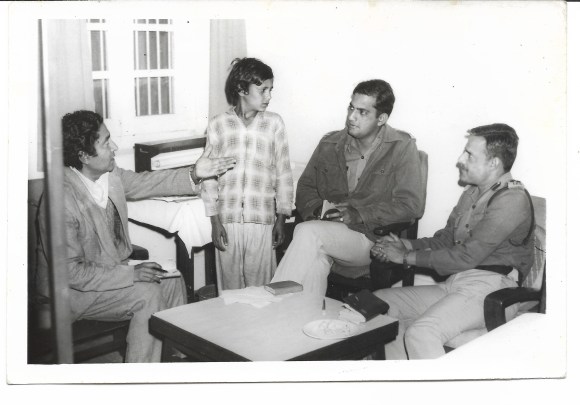

I went to the site. As the SP, whenever I travelled I had a driver, a gunman, and sometimes also my PA. In case I remembered, or noticed, something my PA would record it. We arrived at the spot. The police were standing there. There were dead bodies on the ground. We stood a little away from them, discussing how it had happened, who did what, and had the dacoits been recognized.

Suddenly there was a burst of fire from an automatic weapon. All of us took position in a reflex action arising from our training. We looked up, to see someone standing with his rifle over the dead body of one of the dacoits. He had emptied all the bullets in his gun into the corpse!

The DSP and inspector chorused, ‘Sir! He is your gunman.’

I realized that this was my replacement gunman; my regular gunman was on leave.

Now this was my responsibility to go and disarm him!

I walked up to him. He was standing there, stunned at what he had done. As I came closer, he dropped his weapon and fell at my feet, sobbing. Lifting him up I asked, ‘What happened? Why did you do that?’

‘Sir, it is this fellow…’ he said, and a frenzy of abusive words started pouring out of him. Words that my men would never ordinarily use in front of me. ‘This is the guy who raped my sister!’

The point is, even after the man was dead, the atrocity he committed was not forgotten. Revenge must be taken, even on a dead body.

(Sourced and edited by Ratnottama Sengupta with permission from the family of the late author.)

About the Book

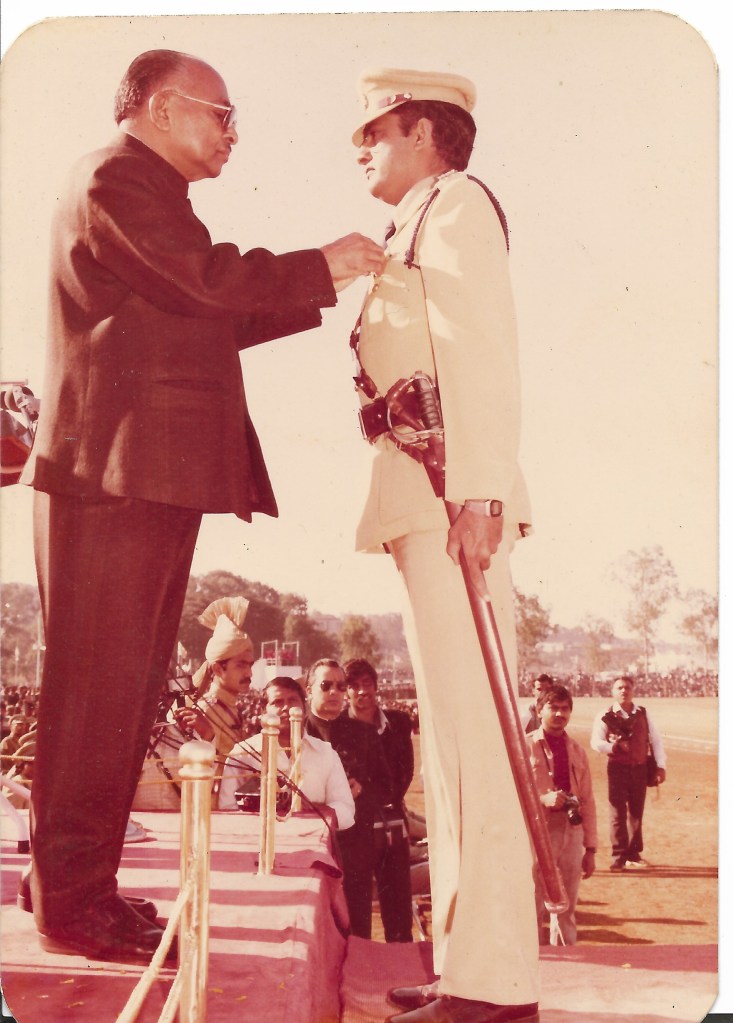

When he heard Mr Patel say, ‘These medals are to be earned, not to be purchased,’ Vijay was secretly filled with the determination to earn his own medal.

In the course of time, Vijay Raman not only earned the President’s Police Medal for Gallantry, but also went on to create history in each of his postings all over India.

He was a simple and straightforward cop, one who was extraordinarily courageous. His untimely demise in 2023 was preceded by many near-death situations—described in this book—which he was miraculously lucky to survive.

This is a real-life hero’s first-hand account of Paan Singh Tomar and his dacoit gang being decimated in a 14-hour dusk-to-dawn encounter; the surrenders of Daku Malkan Singh and Phoolan Devi; leading from the front and putting an end to the notorious terrorist Ghazi Baba; investigating the infamous Vyapam scam; dealing with the horror of the gas tragedy in Bhopal; guarding the life of four Indian prime ministers as one of the handpicked officers of the Special Protection Group; and beating the Guinness World Record for circumnavigating the globe.

The chronicles of Vijay Raman form a book of adventure, of remarkable events—giving readers precious insights into the making of a legend. As he reviewed the book’s final chapters, he asked his wife Veena incredulously, ‘Did I Really Do All This?’

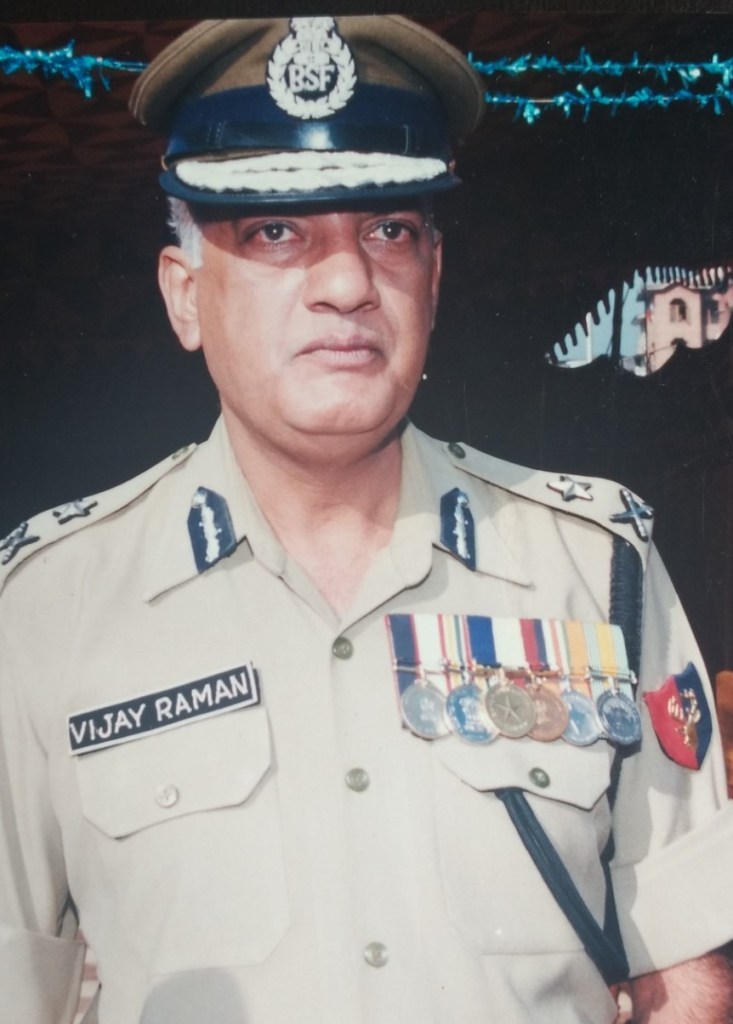

About the Author

Vijay Raman, an IPS1 officer of the Madhya Pradesh cadre, was a legendary figure in Indian policing, celebrated for spearheading the elimination of dacoit Paan Singh Tomar and his gang in Chambal, and later leading the operations that liquidated the dreaded terrorist Ghazi Baba.

Growing up in Kerala and later a gold medallist in law at M.S. University Vadodara, his career achievements were spread across India. He also broke the Guinness World Record for circumnavigating the globe!

Vijay Raman’s bravery, intellect and striving for adventure were always secondary to his integrity; he was committed to upholding the law in even the most complex situations. He passed away in 2023.

Click here to read more about the book and the writer.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International