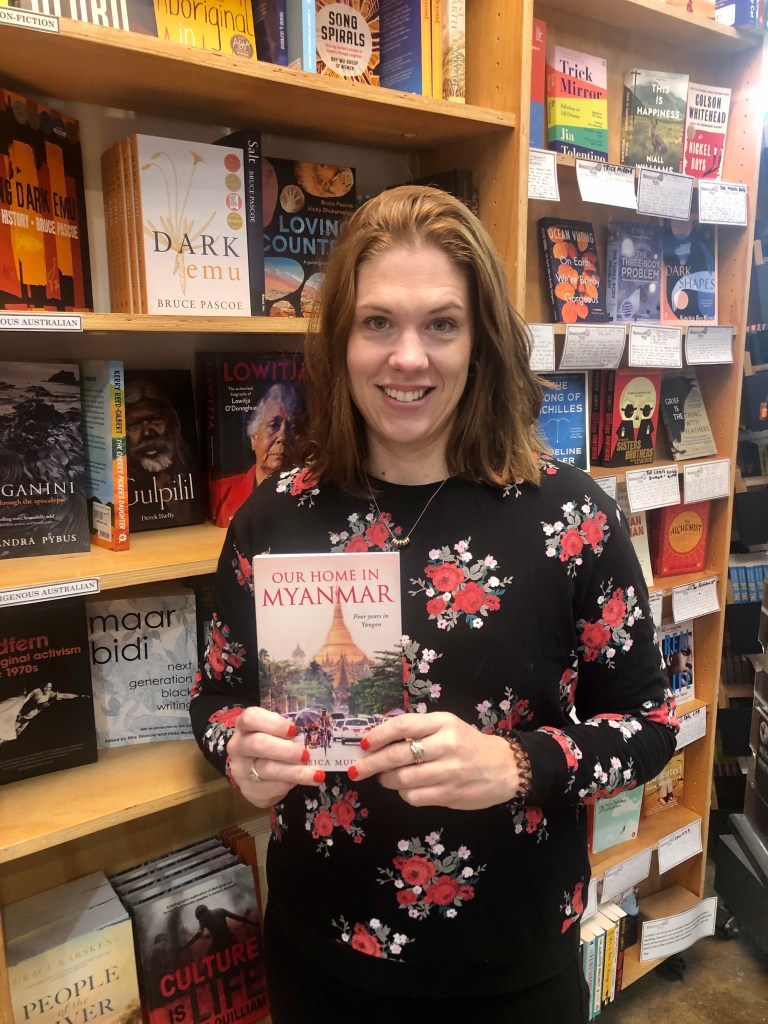

Keith Lyons interviews Jessica Mudditt, who spent four years in Myanmar and wrote a book about it

Australian author and journalist Jessica Mudditt studied and worked in the UK, but it is the seven years she spent in Bangladesh and Myanmar which seems to have made the most significant impact on her professional career and personal life. Mainly covering business, technology and lifestyle, her articles have appeared in The Economist, BBC, The Telegraph, The Guardian, CNN, GQ and Marie Claire.

She lived and worked in Myanmar’s former capital Yangon in the mid-2010s, and after returning to Australia, Our Home in Myanmar – Four Years in Yangon (Hembury Press, May 2021) was published with an Epilogue placing the book’s focus in the context of the military coup which stole back power in February this year following democratic elections.

From Sydney, Jessica reflected on her time in Myanmar, and the recent events which have curtailed hopes for democracy, freedom and economic growth.

Looking back on what happened this year, does it make your time in Myanmar seem more special?

In a way, it makes even my most happy and carefree memories bittersweet. When I was reading back over the book as part of the editing process, some of the situations I described became quite poignant, knowing what I know in hindsight. For example, after the 2015 elections, it was Senior General Min Aung Hlaing who was the first to come out and say that as the commander-in-chief, he would respect the election results and the will of the people in voting for Aung San Suu Kyi’s party. Five years later, it was he who staged this terrible coup and is holding the entire country hostage. What changed for him, I wonder, between then and now? It was like he tried the shoe on one day and decided that it didn’t fit.

If you were still in Myanmar at the time of the coup, would you get out or stay given the dangerous time for journalists right now?

I would leave. It is simply too unsafe. There are no newspapers left to write for at any rate, other than The Global New Light of Myanmar. Mizzima and Irrawaddy and others have been stripped of their operating licenses and as such, are illegal entities. If you go on The Myanmar Times website, it turns black, and then a pop-up notice announces that the newspaper has been suspended for three months. That was six months ago. There are very, very few foreign journalists left inside the country. Of course, every expat was heartbroken to leave and many have expressed that they feel guilty about the people they have left behind. Everyone is in an impossible situation right now.

You added to the book from 2015 with updates on where some of the key players are now: The Myanmar Times co-founder Ross Dunkley was pardoned after the coup and is now back in Australia, have you had any contact with him, and if so, how do you feel about how it all panned out for him?

When Ross got a 13-year sentence in 2019 on drugs charges, I worried that he may not survive such a long period in prison. He is not a young man anymore. However, Ross turned out to be a cat with nine lives. He was released shortly after the coup (he joked in an interview that he is the only person to have benefitted from the coup). What astounded me was that despite everything he has been through in Myanmar, he expressed a wish to return there. I suppose it is his home, after all the years he has spent there. But even so! I sent him a message on Facebook just saying I was glad and relieved for him. However, I don’t think he has logged onto it since his release.

Photos of jailed former advisor to Aung San Suu Kyi, Sean Turnell, being vaccinated were released recently; are you concerned about his fate and also that of journalist Danny Fenster from Frontier who is also in Insein?

I feel sick when I think about them. I don’t know Danny personally, but Sean was a source for a few stories, and I met him in Sydney. I have so much respect for him, and he was always so kind and helpful. I am friends with his wife, Ha Vu, on Facebook, and her anguished posts are deeply upsetting. Yesterday was her birthday and she wrote that it was the first time in a decade that her husband hadn’t been able to wish her a happy birthday. She knew it would upset him. Sean has done nothing wrong – nor has Danny, of course – and I just wish that the military would let them go – along with the other 6,000 innocent people they have arrested.

Do you think you were lucky to have been in the country during its opening up and transformation?

I was incredibly lucky. The pace of change was so fast that I often had the sensation that I was watching history unfold in front of me. That may never happen again in my life. The liberalisation of the media was incredible. As a freelance journalist, when I had an idea for a story, I would google the topic to see what had been previously written. There were many instances when there was virtually nothing at all because it had never been possible to write of such topics under the draconian censorship laws (most of these laws were lifted not long after I arrived). I wrote the first stories on Myanmar’s human hair trade, cobras being found inside peoples’ homes in Yangon, children with cancer and elderly care. Journalism was challenging in Myanmar because there was a dearth of reliable data and finding sources could be tricky, as people were not always willing to speak as they still mistrusted the military (with good reason, it turned out). But it was also rewarding because it gave people the chance to tell their stories for the first time, and to provide information to readers that had perhaps not been in the public domain before.

What do you think attracted others from overseas to witness, take part or benefit from the changes?

One of the reasons I loved living in Yangon was because the ex-pat community was very interesting. At a party, for example, I could walk up to someone and ask, “What brought you to Myanmar?” or “What are you doing in Myanmar” and the answer would just about always be fascinating. Myanmar is a beautiful country with wonderful people, but it isn’t an easy place to live and many of the things associated with the ‘good life’ are unavailable. I think that if you moved to Myanmar, you wanted something different out of life, or to do things in a different way.

I’m pretty sure that there were a host of motivations though, and I’m sure that a few were motivated partially by greed. Myanmar was an untapped market with a large population, although spending power is comparatively low. There were also few laws regulating business dealings, so it was a bit of a wild west and that attracted a few shandy operators. But I think, for the most part, people’s intentions were good. They were there because they wanted to make a difference as well as to witness something really historic, in a political sense.

As a woman in Myanmar how safe did you feel, and do you think that helped or hindered your work?

I felt safe in Myanmar, as it has some of the lowest crime rates in Asia. I remember reading in Lonely Planet that muggings and pickpocketing are rare, and that if you accidentally drop money on the ground in a big city like Yangon, it’s more likely that someone will come chasing after you to return it. That actually happened to me. I would sit at a beer station in the evening with my bag slung behind my chair or on the ground or whatnot, and I never gave it a second thought. I wouldn’t do that in Sydney.

Sexual harassment is nowhere near as prevalent as it is in places such as India. In saying that, I am referring to sexual harassment against expat women. There were frequent reports of Burmese women being groped on crowded buses, for example.

Someone in Yangon told me last week that even though the current situation is desperate, and millions of people are starving and displaced, there is a huge amount of cooperation among the people, who help each other in any way they can. Sadly, we all know that the criminals in Myanmar are the military. The reams of razor wire that sit atop six-foot fences around people’s homes are there not because there are a lot of burglaries, but because the military comes for people in the night. They were doing it for decades before I arrived, and they are doing it again now.

What misconceptions about Myanmar do you think are held outside the country?

I’m not sure if it’s a misconception, but Myanmar’s political history is so complex that it can be difficult for people to get their head around it, and difficult to explain. The first thing most people say to me when the subject of Myanmar comes up is “What is the deal with Aung San Suu Kyi? I thought she was a good person – why did she fall from grace?” Or they will say they have heard of the terrible situation with the Rohingya, but they don’t understand how the genocide came about, or why they are still living in refugee camps. Most people outside Myanmar assume that Buddhism is a religion of peace, so they don’t understand why so much violence has taken place, or that Buddhism can turn militant and be infected with extreme nationalism.

Were you more surprised about the frosty reception you got from fellow ex-pats at your first newspaper job, or the treatment you got working for a newspaper once considered a mouthpiece for the military and government?

I was more surprised by the frosty reception I got at The Myanmar Times. I was wildly excited to be working there and went through a lot of difficulties to get my first visa (I brush over it in the book, but Sherpa and I initially applied from Bangladesh and were denied visas, so in the end we had to apply from Thailand). My colleagues at newspapers in Bangladesh had always been fantastically friendly, so it just never crossed my mind that my expat colleagues in Myanmar wouldn’t be friendly. My expectations were way too high, but I was pretty crushed, I have to say. Over time though, things improved, and I ended up with a terrific group of friends at work. We had a lot of fun nights out too.

My colleagues at The Global New Light of Myanmar were really kind and wonderful. I learnt so much about Myanmar from them, both on the job and during the casual conversations we’d have while smoking cigarettes or drinking whisky together after work. Myanmar people are so kind –so it wasn’t my colleagues’ kindness that surprised me. It was how strongly opposed to the military they were. I had not expected them to be staunch supporters of Aung San Suu Kyi, or even to themselves be former political prisoners. Many worked at the state-run newspaper because it was one of the few opportunities to use English in a professional context. To me, it showed just how pervasive the desire is for democracy and human rights among the people of Myanmar.

When did you get the idea for writing a book about your time in Myanmar?

I got the idea after I returned from Myanmar to Australia. Funnily enough, while I was living in Myanmar, I had been writing a book about Bangladesh. When I got back to Australia, I had no luck getting a publishing deal for the memoir on Bangladesh, so I decided to put it aside and start one on Myanmar. I started it in 2018 and finished it in April 2021. I’m glad that I decided to do that, because it would be hard to write the same book knowing that a coup would take place after I left. I am sure I would write it differently — with less optimism. As I mention in the epilogue, I thought I was simply writing about the ‘new Myanmar’ and that many books would follow in the same vein. I had no idea that I was inadvertently writing a history book.

In light of the events of 2021 with the military coup and Covid, do you see any hope for Myanmar, or is it a failed state?

There has possibly never been a darker time in Myanmar’s history, with the twin crises of COVID-19 and the military takeover to endure. But I don’t believe that this is how the story ends for Myanmar. It is evident that the people are unwilling to give up their democratic freedoms and human rights – I get the sense that they will fight until there is no one left standing.

However, the country is on the brink of becoming a failed state, if it isn’t already, and the suffering has already been immense. I know from my time in Myanmar that building back after half a century of dictatorship and a mismanaged economy was already difficult enough – I worry about how much this puts the country back on the path to progress. I take a long-term view of things though, and I believe that democracy will be restored, and the military will be booted out of all aspects of civilian life, including their 25% quota of parliamentary seats. I have no idea when this may occur, but I do believe that it will.

Click here to read an excerpt of Our Home In Myanmar.

Click here to read the review of the book.

Keith Lyons (keithlyons.net) is an award-winning writer, author and creative writing mentor, who gave up learning to play bagpipes in a Scottish pipe band to focus on after-dark tabs of dark chocolate, early morning slow-lane swimming, and the perfect cup of masala chai tea. Find him@KeithLyonsNZ or blogging at Wandering in the World (http://wanderingintheworld.com).

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL