By Randriamamonjisoa Sylvie Valencia

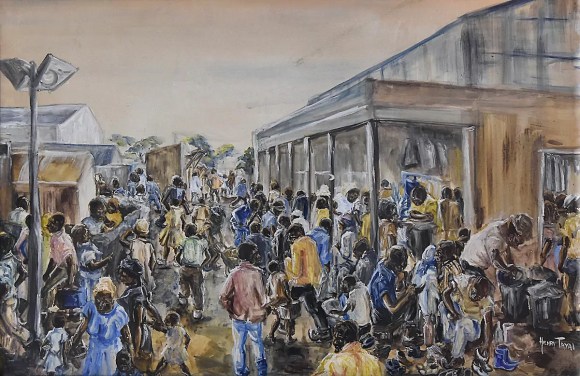

For as long as I can remember, I have been an introvert — this is who I am and will always be. Yet, few believe it. I come from Madagascar, a distant island where the people are called the Malagasy — a community bound by culture, tradition, and a shared sense of identity. Malagasy people are known for their warmth and generosity, often revealing a talkative side as they delight in conversation, and playful exchanges. In contrast, I am reserved — a shy person who expresses myself freely only when comfortable and among those I trust.

As a child, I was the most talkative among my siblings, recounting every detail of my school day to my parents. I delighted in describing the funny expressions my primary school teacher made while explaining lessons, or the mischievous boys who always stuck their chewing gum on the pupils’ desks and all the tasks I had accomplished. I wanted my parents to know I was doing well, that the teacher praised me, and that I helped classmates who struggled.

Both my parents are very talkative, especially my father, from whom I inherited the gift of words. Speaking in front of my family comes naturally, yet in front of others, my words often falter — a fear that has always troubled me. I speak freely only with those I know well— my family and a few close friends.

Facing a large audience has always been daunting. My father encouraged me to confront this fear, to be confident, and to meet the audience’s gaze. I tried many times: presenting in group projects, speaking as a class representative, even addressing an audience at a classmate’s parent’s funeral.

As I grew older, my determination to overcome this fear grew. I devoured books and videos on public speaking, eager to communicate with confidence. My first real test came in 2018, when I delivered a speech in a Japanese language contest. I had loved Japanese language since childhood, captivated by its culture, and dreamed of becoming fluent. Entering the contest was a dream — an opportunity to speak publicly and a chance to win a trip to Japan.

I was guided by two close friends who practiced with me daily. They corrected my mistakes, offered feedback, and most importantly, encouraged me. Having known me for years, they understood how terrifying standing on stage could be, yet they supported me out of love, friendship, and belief in my potential.

During rehearsals, I gave my utmost effort, memorising the script when necessary. Still, doubts lingered about meeting expectations, conquering fears, and not disappointing those who believed in me. The days of practice passed quickly, and soon, the big day arrived. Nervous at first, I gradually became more at ease while speaking. I managed to control my anxiety but knew my performance was imperfect. I focused on each word, yet my mind occasionally went blank, struggling with the judges’ questions. Embarrassment washed over me; I feared I had let my friends and family down.

In the end, I did not win the first prize, but my closest friends congratulated me. They reminded me that the true milestone was stepping onto the stage, speaking in front of an audience, and maintaining composure. Their encouragement helped me realise that courage and effort mattered more than the outcome itself.

As an introvert, talking to strangers is challenging, let alone addressing a crowd. Hearing the words “public speaking” makes my stomach tighten, palms sweat, and heart race. Stage fright, fear of facing many people and sharing my thoughts has always been real. Each time my name is called, I shake, my mind blanks, heart pounds, mouth dries, and confidence seems to vanish before I start. Yet, I have never lost hope. Deep down, I knew a strength within me would help rise above fear and grow into a better version of myself.

One year later, I stood again in the same contest. This annual competition was a goal I refused to let go of. As before, my friends encouraged, pushed, and trained with me every day until the D-day. Their support gave me the strength to continue. I prepared even more fiercely — joining language clubs and volunteering in storytelling activities. But it was not easy. I never felt comfortable speaking or working with strangers. I was told teamwork required discussion, sharing, and collaboration — a nightmare for an introvert.

Solitude had been my ally, yet suddenly, I was surrounded by people of all ages and personalities. Cooperation was no longer optional. However, through this challenge, I discovered an important truth: whether introverted or extroverted, whether silent or talkative, we must learn to connect with others. Survival and growth depend on collaboration and support.

The big day of the speech contest arrived in May, a season of transition between summer and winter. I arrived at the hall just in time, accompanied by a close friend. A staff member guided me to my seat, only a few meters from the judges. I felt cheerful, and calm, even giving a fist bump to nearby contestants. For the first time, I felt truly ready to give a speech — optimistic, and at peace. Perhaps it was the preparation or my friends’ wholehearted support, or maybe I had begun to trust myself.

There were four contestants in the advanced level, and I was the last to speak. Each of us hoped to win the grand prize — a trip to Japan. I did not worry about the others. I believed in my success and was determined to win first place. Just days before, I even dreamed of visiting Japan, so nothing could stand in my way.

Finally, it was my turn. I adjusted the microphone, greeted in Japanese, and bowed to the judges and audience. I spoke for about five minutes on how Malagasy parents raise children. Three judges asked each two questions. Thanks to countless practice hours and mock questions and answers sessions with my best friends, I answered every tricky question. For the first time, right after my speech, I felt like a winner.

The event lasted about three hours, and the final verdict came. The Master of Ceremonies announced winners, starting with the beginner level, then the advanced. Among the four in my category, only two remained. The Master of Ceremonies paused dramatically before announcing the first-place winner… and pronounced my name. I whispered a silent thanks to God. This result — the goal I had worked so hard for — had become reality. The trip to Japan was the reward, and even more importantly, I had overcome stage fright. I spoke naturally and confidently in front of the audience — another milestone achieved.

Later that year, in 2019, I visited Japan for the first time. The experience was magical. I met wonderful people, explored my favorite country, and fulfilled a long-cherished dream.

Six years later, I returned to the Land of the Rising Sun—this time as an international student. I now live in Tokushima prefecture, which is in southeastern Japan, far from the bustling cities, in a quiet countryside where few tourists venture. Yet, the city and its neighbourhoods are simply wonderful. It is peaceful, surrounded by greenery, and while the locals may seem reserved, they are incredibly welcoming. Even with some grasp of the local language, adapting to a new country as a foreigner is challenging. Still, thanks to the support of my seniors and friends who have lived here for years, I managed to navigate my first six months successfully.

The city where I live hosts an annual Japanese speech contest open to foreigners who have been residing here for some time. I was encouraged to participate, partly because I could speak some Japanese, and partly because it was a great chance to gain experience. I thought, why not? After all, I gradually grew more comfortable speaking in front of others.

This time, participants could choose their own topics, though it was suggested to focus on their experience in Japan or explore cultural connections between their home country and Japan. I was eager to participate, but selecting a topic was harder than I expected. Inspiration felt scarce, and I had no clear direction. Still, I knew that finding my own perspective was key to making the speech meaningful.

Overwhelmed by my studies, I barely noticed the passage of time. Before I knew it, the deadline had arrived. I had not written a single word, though ideas swirled in my mind. I opened my laptop, took a deep breath, and began writing everything that came to my mind. Reflecting on my experiences in Japan, I realised that people often struggled to pronounce my name correctly. That inspired me to talk about the hidden culture behind Japanese and Malagasy names.

With my theme set, I focused on making my speech coherent and captivating. I tend to draw inspiration at the last minute. I wrote, rewrote, and proofread repeatedly, staying up all night without noticing morning approaching.

Finally, I finished my manuscript and emailed it to one of my Japanese teachers to check for grammatical errors. She responded immediately, and her quick proofreading allowed me to submit my speech on the deadline. I felt relieved, yet strangely nervous, a sensation I could not quite describe.

Six years have passed since I last spoke in front of an audience. Preparing another speech made me feel nostalgic, bringing back memories of long rehearsals, the advice of my best friends, and countless sleepless nights.

A month after submitting my manuscript, I received an email from the event organizer announcing my selection. I was among the fourteen candidates chosen to compete. I whispered a quiet “wow,” but doubts immediately surfaced. I had two months to prepare. To understand what awaited me, I watched recordings of previous competitions, while my seniors and Japanese teacher helped me refine my speech.

Four students were selected from my university. The other three were Asian students with extensive experience in Japanese language and culture. They read Kanji (Japanese characters)effortlessly and conversed naturally. And then, there was me. Though I had been exposed to Japanese language and culture since childhood, memorising every character reading and grasping dialects was never easy. Back in my country, despite growing interest in Japanese language and culture, opportunities to use it in daily life remain limited. Once again, I faced a new challenge—this time in the Land of the Rising Sun.

Time flew, and soon the two months of preparation had passed. Finally, the big day arrived. Early that morning, a kind university staff member greeted us with a bright smile. As I descended from my dormitory, I saw her waiting by her car near the main gate, bowing politely. Her excitement was palpable. Three of us rode in her car; she asked about our preparations and told jokes, perhaps to ease our nerves, which were all visible.

After twenty minutes, we arrived at a large building and walked up to the fifth floor through corridors decorated in traditional style. Japanese architecture and design have always fascinated me, and I was struck by their beauty once again. The event hall was medium-sized, with a small table at the entrance holding our name tags.

One by one, the other candidates arrived. We were then led to a smaller room for a preparatory meeting. While waiting, we chatted briefly to get to know one another. The competition began in the early afternoon. We were instructed to enter the hall one by one, greeted with warm applause. Observing the other candidates, I could tell they were ready. Fourteen contestants competed in total. Thirteen were Asians from countries including China, Vietnam, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. I was the only African, from a distant country few people knew. Before each speech, the Master of Ceremonies shared a brief anecdote about the candidate’s country, offering the audience a glimpse into its culture. Each contestant then delivered a five-minute speech.

There were two types of awards: the Golden Prize for first and second place, followed by four Silver Prizes. I had hoped to place among the top five while preparing my speech.

As I listened to the first three candidates, I was deeply impressed. Their speeches were powerful, emotional, and delivered with near-native fluency. I was surprised by how advanced and impressive their speaking skills were. I was the sixth speaker. Perhaps it had been so long since I last addressed an audience, or perhaps it was the absence of my closest friends but standing alone in a foreign country in front of strangers was overwhelming. My hands trembled. When my name was announced, I feared I might not endure those five minutes on stage.

Still, I stood before hundreds of people. I bowed, held the microphone firmly, and began. My heart raced and sweat ran down my face and back. Gradually, the pressure eased. When I shared the example of the longest name in the world—from my country, the audience reacted with surprise and amusement. I realised how attentive they were and regained inner calm. Although I forgot one line, I finished my speech smoothly and expressively.

The remaining eight candidates were equally impressive. Their eloquence was such that, with eyes closed, one might mistake them for native speakers. It was the highest-level contest I had ever participated in. Each theme and presentation were unique, and every contestant spoke with confidence. I doubted whether I would receive a prize, but reassured myself that even without one, the experience was worthwhile. Most participants had lived in Japan for over three years, and the Chinese and Taiwanese contestants were especially strong in oral expression. Yet, standing among such talented competitors was an honor.

After a break that was supposed to last twenty minutes but stretched to fifty, results were announced. They began with six Encouragement Prizes. I thought I might be among them, but my name was not called. Two more awards followed, still not mine. A friend nudged me, whispering, “Congratulations!” I replied, “Stop joking. Congratulations to you instead!”

Finally, the Silver Prizes were announced. They first called my country, then my name. The applause and cheers overwhelmed me, and tears welled in my eyes. I had not expected to win a Silver Prize, given the competition’s level. One friend from my university won the Golden Prize, and the second Golden Prize went to a Vietnamese contestant.

Participating in such a high-level competition was a tremendous challenge. Every step—from manuscript preparation to standing on stage—pushed me beyond my comfort zone. Yet, when it was over, I felt immense pride. I had once again delivered a speech before a large audience, this time in the country whose language I had cherished for years.

Though I had been nervous, the audience remained unaware. Their attentive expressions and warm applause carried me through. Afterwards, my Japanese teachers praised my performance, saying I had done exceptionally well. In that moment, I realised every hour of preparation, every doubt, and every fear had been worthwhile. I had faced a formidable challenge, stood my ground, and expressed myself fully, a reminder that courage, practice, and determination can transform daunting experiences into triumphs. It is a memory I will treasure forever.

.

Randriamamonjisoa Sylvie Valencia is from Madagascar and is currently studying in Japan as a trainee student. She enjoys reading, writing, listening to music, and traveling to explore new cultures.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International