If religion has bound people of different lands, religion has also crafted gulfs between people who shared the birthplace and spoke the same language. If religious hatred led to the holocaust, religion became the cornerstone of India’s Partition. The crimes against humanity in Bosnia also were rooted in religious intolerance, as Ratnottama Sengupta retraced when her brother, Dr Dipankar Ghosh wrote to her from Bosnia-Herzegovina, as part of the peace-keeping forces in 1996.

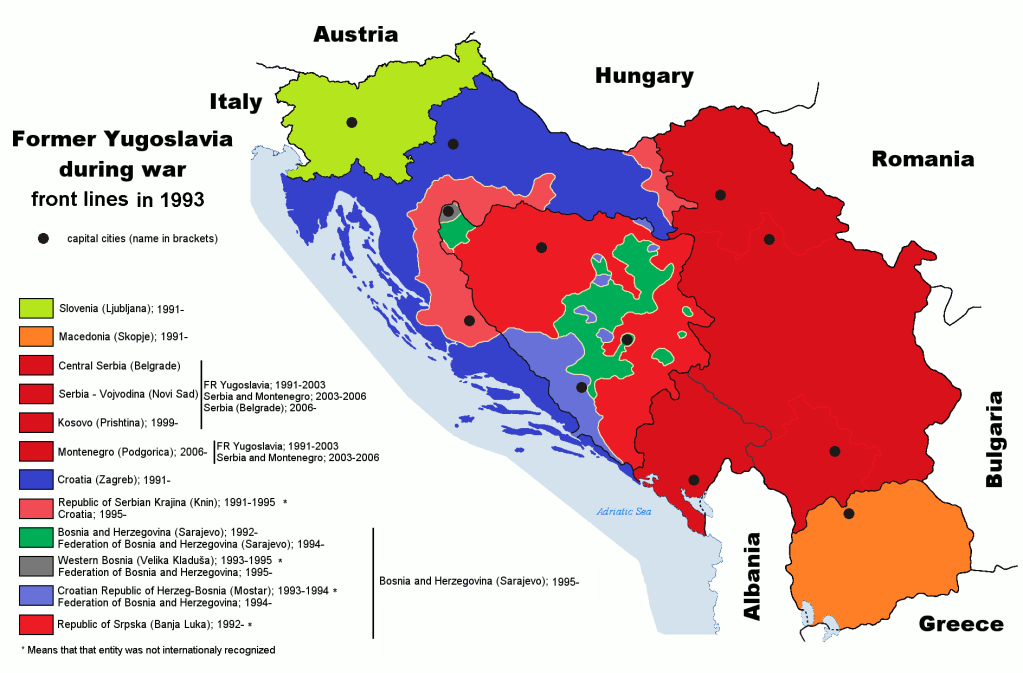

The Bosnian War (1992-1995) was an immediate fallout of the break-up of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It began to disintegrate when Slovenia and Croatia seceded in 1991. Serbia, the largest constituent in the Republic of Yugoslavia, did not want Croatia’s independence as a large Serb minority lived in Croatia. But the rest of the state declared national sovereignty in October 1991 (two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall) and held a referendum for independence on 29 Feb 1992.

Bosnia, the largest nationality, was home to Muslim Bosniaks – they wanted Bosnia to be a unitary multi-ethnic state. The Serbs wanted to be independent if not to unite with Serbia. Likewise, the Croats wanted significant autonomy for their majority areas or secession to Croatia.

The referendum favoured independence, but the Bosnian Serbs opposed this, as they aimed at creating a new state – Republika Srpska (RS) that would include Bosniak majority areas. So, their political representatives boycotted it. And a day before the outcome of the referendum, on 28 February 1992, the Assembly of the Serb People in Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted the Constitution of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Eventually, the European Union formally recognised the newly constituted Republic, as did the UN. It was inhabited mainly by Muslim Bosniaks, Orthodox Serbs, and Catholic Croats. As this Republic gained international recognition, the earlier Cutiliero Plan proposing a division of Bosnia into ethnic cantons collapsed.

Now the Bosnian Serbs, led by Radovan Karadzic and supported by the Serbian regime of Slobodan Milosevic and the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA), mobilised their forces inside Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to secure ethnic Serb territory. Soon war spread across the Balkan land, accompanied by ethnic cleansing.

Siege of Sarajevo (1992-1996): The Bosnian Serbs who would settle for nothing less than a new state, Republika Srpska (RS), now encircled Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia-Herzegovina. With a siege force of 13,000 stationed in the surrounding hills, they assaulted the city with artillery, tanks, and small arms. The army of RS, which had transformed from the Yugoslav Army units in Bosnia, fought the army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH).

Inside the city ARBiH, which was the Bosnian government’s defence force composed of Bosniaks and Croat forces in the Croatin Defence Council (HVO), was poorly equipped. It could not break the siege and for six months, the population of Sarajevo lived without gas, electricity or water. It is estimated that of the 13,952 killed during the siege, 5434 were civilians.

Within a year increased tension between the Bosniaks and the Croats led to escalation of the Bosnian war, in 1993. Here on, the war was characterised by bitter fighting, indiscriminate shelling of cities and towns, ethnic abuse, forcible transfer and systematic mass rape of Bosniak Muslim women – perpetrated mainly by Serbs and, to a lesser extent, by Croat and Bosniak forces. Events such as Markale massacre and Srebrenica genocide, perpetrated to raze the Bosniak’s morale and willingness to fight, became iconic of the conflict.

Markale Massacre: In February 1994, the open-air market in the historic core of Sarajevo. Mortars were shelled. This act of targeting civilians in the marketplace was carried out, it was later confirmed, by the Army of Republika Sprska (VRS).

Initially the Serbs were militarily superior due to the weapons and resources from the JNA. Eventually they lost momentum as the Bosniaks and Croats allied against RS following the creation of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1994.

The repeat shelling of the Markale Market in August 1995 prompted the NATO airstrikes against Bosnian Serb forces and eventually led to the Dayton Peace Accord. The peace negotiations were held in Dayton, Ohio and signed on 21 November 1995.

Srebrenica Genocide: In July 1995, more than 8000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys in and around the town in eastern Bosnia were killed by the Bosnian Serb Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) under the command of Ratko Mladic. Prior to the massacre UN had declared the besieged enclave of Srebrenica a “safe” area but had failed to demilitarise the area or break the siege of Sarajevo. By 2012, close to 7,000 genocide victims were identified by DNA analysis of the recovered body parts.

Some Serb accounts say that the massacre was in retaliation of civilian conflicts on Serbs by Bosniak soldiers from Srebrenica. This claim has been rejected by the UN and ICTY as “bad faith attempt to justify the crime against humanity”.

US Inaction: The United States took no action till 1995 against the smuggling of arms that had become rampant. It was widely believed that the CIA funded, trained and supplied the Bosnian Army. EU intelligence sources maintained that the US organised arms shipment to Bosnia through its Muslim allies. Pakistan, for one, ignored the UN ban that declared it illegal for other Muslim countries to supply arms in the war. It not only supplied arms and ammunition to Bosnian Muslims, it also airlifted anti-tank missiles.

Serbia did not fight but supported RS with money, arms and volunteers. Croatia too did the same for Croats.

The war ended with the signing of the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina in Paris on 14 December 1995. British soldiers were first deployed in 1992 to protect aid convoys in Bosnia during the vicious civil war. They stayed on for peacekeeping duty.

War Crimes: Radovan Kradzic, the first President of Sprska during the Bosnian war, was a trained psychiatrist who was also known for his poetry. But the co-founder of the Serbs Democratic Party was declared a War Criminal. He was hunted down after 12 years as a fugitive in Belgrade and Austria, and extradited to the Netherlands which was then heading EU. There the International Crimes Tribunal for Yugoslavia (ICTY) convicted him on 11 counts of crimes against Bosniak and Croat civilians. Found guilty of the genocide in Srebrenica, he was sentenced to 40 years imprisonment.

Reportedly hundreds of people had demonstrated in his support. Others pleaded that Bosnia and Serbia could not move ahead economically as long as he was at large.

By 2008 ICTY had convicted 45 Serbs, 12 Croats, and 4 Bosniaks of War Crimes against Humanity. Estimates suggest that around 12,000-50,000 – mostly Bosniak – were raped, mainly by Serb forces. About 1 million people were killed and 2.2 million were displaced. This makes the Bosnian war the most devastating conflict in Europe since the end of World War II.

Net Outcome: The Bosniaks accomplished their goal of independent Bosnia. But the Serbs preserved their territorial gains a change in the demographic and self-rule in Republika Sprska. Also, the ethnic cleansing led to changes in the demographic composition of the Bosnian region – with the Serbs gaining the most.

History of the Conflict: The roots of the Bosnian War lies in the history that dates back to the 6th and 7th century when the region came to be inhabited by Slavic tribes. Bosnia was conquered in 1463 by the Ottoman Turks. Under their rule, large sections of the population converted to Islam while the rest remained either Orthodox Christians or Catholics. The Christian Orthodoxy came to be associated with Serbian nationality and Catholicism with Croat nationality. It is interesting to note that all these people spoke the same Slavic language.

Ethnic violence has been endemic in Bosnia and Herzegovina that had been under Austrian rule (1878-1918) before becoming a part of Yugoslavia. Violence engulfed it during WW2 when it was under Croatia, a puppet of Nazi Germany. In 1943-44, most of Bosnia was conquered by Serb-dominated Communists. Consequently, when WW2 ended, Bosnia became a constituent of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It was led by Josip Broz Tito (1892-1980), an ethnic Croat who tried to create a common Yugoslav identity based on adherence to Communist ideology. When that glue wore off, the nationalist separatist forces surfaced again.

*

Dipankar Ghosh, since he went to Pune’s Shivaji Preparatory Military School as a teenager, was mentally equipped to face the tribulations a war brings in its wake. His graduation from Kolkata’s Neel Ratan Sircar Medical College armed him to care for the ailing. And, being the firstborn of celebrated writer Nabendu Ghosh, he had a flair for writing.

All three qualities surfaced whenever the doctor, who retired as a Colonel in Britain’s Royal Army Medical Corp, put pen to paper. And he did that whenever he felt the urge to touch base with his parents in Bombay. From wherever he was camping — Belize, Belsen, Brunei, Cyprus, or in the Gulf War…

In the process, he breathed life into the now lost art of writing letters — which often became travelogues… like this letter to his father:

*

Lt Col D Ghosh, RAMC

RMO, 1 WFR

SHOE Factory, Mrkonic Grad

BFPO 551.U.K.

5th July 1996

Dear Baba,

I have just received your last letter from Bombay. I was worried about your health, which is why I rang you last night. Sorry it was so late. There was quite a queue for the phone, so I had to wait for my turn, Lt Col notwithstanding! I am reassured that you are okay.

I am sorry the line was so poor, but it is a satellite line, which travels from Bosnia to the USA then is beamed on to India — hence all the static. Mind you, it is full of static when I speak to Lesley and Children in the UK too. Sadly, it is only an outgoing line, which takes call out, but no incoming calls. If you need to get in touch with me urgently, the best thing would be for you to ring Lesley and she can get in touch with me via the Ministry of Defence.

We have been out in Bosnia for just over three months now, and the problems here seem to be in a state of very uneasy peace, now that Dr Radovan Karadzic has finally handed over the reins of power (Oh Yes!?). We are somewhat concerned that the proposed elections in September might bring about fresh unease and disturbance, even without Dr Karadzic at the hustings, and we might be, willy-nilly, dragged into a situation of tension to try to maintain peace. Nonetheless, the Bosnians are making some efforts to keep the peace, albeit because we are waving a big stick whilst holding out a carrot.

The position is especially delicately balanced for us at the moment, due to the ICFWCB’s (International Commission for War Crimes in Bosnia) declaration of the good Dr Karadzic and his General, Ratko Mladic as ‘War Criminals’ for genocide against the Muslims of Bosnia. There’s little doubt, this is due to pressure from the countries with more than a few spare billions of petrodollar in western banks. We are hoping that we will not need to confront the Bosnian Serbs by having to arrest these two persons (since this was not a part of the Dayton agreement that has laid the framework last year for ending the war ravaging Bosnia for more than three years). These two still hold considerable political sway, and have a significant following in this country.

It seems likely that we (British Army as well as the Americans, much as they might dislike it) will have to stay on in Bosnia for quite a while longer than we’d initially made allowance for. If the yanks want out, I hope we shall pull out as well. The Serbs seem to prefer having us around, to maintain the peace, than any other European nation, as they feel the British army of IFOR has, so far, been fair and reasonable in their dealings with them. (IFOR, you do know, is the NATO-led multinational peace enforcement force here under a one-year mandate).

This was not the feeling they had about us last year though!

The biggest single problem at the moment, which might cause a major flare up for us, is Mostar. The people of this divided town straddling the river Neretva in south-east Bosnia have selected a Muslim majority council: this, the minority Croatian population are unwilling to accept, and have been boycotting. So far the town, which is known for its mediaeval arched bridge Stari Most, has been run by a peace committee from the European community with the help of IFOR, but they have threatened to hand over the council and resign from running it.

This would effectively ring the death knell for the first election in Bosnia. Which would mean that the results of all the country-wide elections, due in September, may be an exercise in futility.

The sad news this morning is that the iconic bridge, which connected the two parts of the city, was blown up by ‘unknown miscreants’ – very likely to have been Croats. Thankfully, Mostar is in the French sector of IFOR overall, so let’s hope and pray.

*

Now to give you some idea of all the other things that I’ve been up to, here in Bosnia. In May we started what we call a G5 project, a ‘Hearts and Minds’ operation to try and persuade the people at the grassroots about the benefits of Peace. This is in a small village called Podrasnica, with medical logistic support — essentially, medicines — from Medicine Sans Frontier (MSF), an international humanitarian organisation that provides medical assistance to people affected by wars, epidemics or other disasters.

Podrasnica is a village of some 950 people and is, like most places in the Balkans, nestled in a valley, about ten miles from our location in Mrkonic Grad.

The people are mostly poor agrarians, eking out a living on small land holdings, or are involved in the logging industry. I run a Primary Health Care Clinic here, twice a week. The locals and also some people from the surrounding villages (though they never let on they are from another village!) are very grateful to have this facility, as they are very poor and many of them are unable to afford the price of medicine, or have transport to travel to Mrkonic Grad, and certainly not to their only surviving big hospital at Banja Luka. We do the basic medical care and also provide them with medicines which are given to us by MSF.

Most of my patients are elderly people and small children, as the majority of young healthy men and women go to other places, bigger cities or towns, to earn a living as best as they can. I’ve never come across so many people, in such a small community, with so much Hypertension amongst them. How much of that is the result of the stresses of war and how much of it due to the Turkish coffee they drink, would be interesting to investigate.

The majority of people are by and large sick of the war, and this is the first time, in five years, some of them will be able to harvest their own crops. The vast quantity of what they grew in the last few years was either commandeered by their own Army or looted by the opposition (Muslims and/or Croats).

The clinic is now quite popular, but it is time consuming as we have to use an interpreter, and I am lucky if I can get through more than 15-20 patients per clinic.

I have a special admirer called Milija (Serbian version of our dear Emily!) who brings us Turkish coffee. She was one of my first patients. She is sixty-two years old, and is a real darling. She doesn’t believe I’m fifty, which is wonderful for my morale!

Later this month, possibly on the 16th, we will ‘hand over’ the clinic to the local Serbs, to continue the clinic with ongoing Medical support from MSF and support from us, if they want it. If they do take over the clinic completely, I shall miss seeing the patients. I’m hoping that they will be happy to allow me to continue the clinic, at least once a week.

The clinic work sustains me through the boredom and the non-events (in real life terms) of the remainder of the week. So far I have had one bottle of ten-year-old Brandy, and a bottle of the local firewater called Sliivo — a fruit brandy they make out of plums). I’ve found out the hard way that it is safer to keep a hand over the little glasses they offer the slivovitz in, otherwise it gets automatically topped up! Even better, so that I don’t drink whilst on duty.

The vegetables are coming on a treat in Milija’s garden, and the palm trees are loaded with fruits, as are the apple trees next to the clinic. Milija thinks they will have a decent harvest, if the peace holds, and she’s trying hard to dissuade her oldest son from drinking too much — otherwise, she says, she will force him to come and see me!

The men who do not have regular employment, and there’s a lot of them about, have become apathetic. So alcoholism is rife, and hence, I think, Hypertension and Peptic disease. All my boys have now developed a taste for Milija’s Turkish coffee, but I try to dissuade Milija, as I am fairly certain that the coffee beans must cost quite a bit.

We always have an interpreter for the clinic, who are generally Bosnian girls, or fellers. They are generally chary (maybe even contemptuous) of the local yorkels, as is normal in all developing nations, and certainly in India. But the vast majority of them seem to have developed a special protective shell, to help them cope with the business of dealing with the needs of their poorer country folks, as the vast majority of them (the interpreters) get paid some DM 1000–12,00/ a month. This is eight to ten times what the ordinary folks in the country earn.

There are some really bright students amongst these interpreters, who have given up career courses in order to take up jobs with IFOR, so that they can look after their families. One of the girls we have with us in Mrkonic Grad was a second year medical student when the war broke out. Another girl, the daughter of a Chemistry Professor (her mother), is a graduate Electronic Engineer. She is trying to get funds organised so she can do a Master degree, and then probably a PhD. What will happen to all these blighted lives eventually, who knows?

I am constantly amazed how well these girls cope with living amongst all of our sex-starved, often foul mouthed soldiers. Some, of course, cope better than others, the youngest being just over 16 years old! IFOR has arranged a free scholarship for her, to study in the UK after she’s done her stint with the Army.

It is hard to be surrounded by so much tragedy and not be repulsed by war and the people who lead nations into them. But draw the experiences of N Ireland into the reckoning and you realise that humankind has still some way to go before being called truly civilised. Amongst all this, when one has to cope with the petty point scoring of the self-seeking people, and self-aggrandizement of personalities around you, then it can get somewhat wearying.

So far I am managing to cope with the changes that have occurred in my life, and find it comforting to accept that “This too shall pass”. Your letter was a solace.

I hope that my dear mother is keeping well. Please convey my pronam and love to Maa. Hope you are both well when this gets to you. I’ve rambled on too long for now.

With pronam and love,

Yours, as ever, Khoka

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and write books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International