Book Review by Somdatta Mandal

Title: Indian Christmas: Essays, Memories, Hymns

Editors: Jerry Pinto and Madhulika Liddle

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

We all know that Christmas Day, the night that Jesus came to earth, bringing with him peace and love for all humanity, is celebrated by Christians all around the world with great enthusiasm and merriment. Interestingly, for a multicultural country like India, Christmas is equally celebrated — not only as a religious festival but also as a cultural one. For a country where less than three percent of the population is Christian, the central celebration is the birth of a child, but it takes on new meaning in different Indian homes. Known in local parlance also as “Burradin”[big day] Indians from all classes and communities look forward to this day when they can at least buy a cake from the local market, shower their children with stars, toys, red Santa caps and other decorative items, and go for a family picnic for lunch, dine at a fancy restaurant or visit the nearby church. This syncretic cult makes this festival unique, and for Jerry Pinto and Madhulika Liddle editing this very interesting anthology comprising of different genres of Indian writing on the topic – essays, images, poems and hymns, both in English and also translated from India’s other languages is indeed unique.

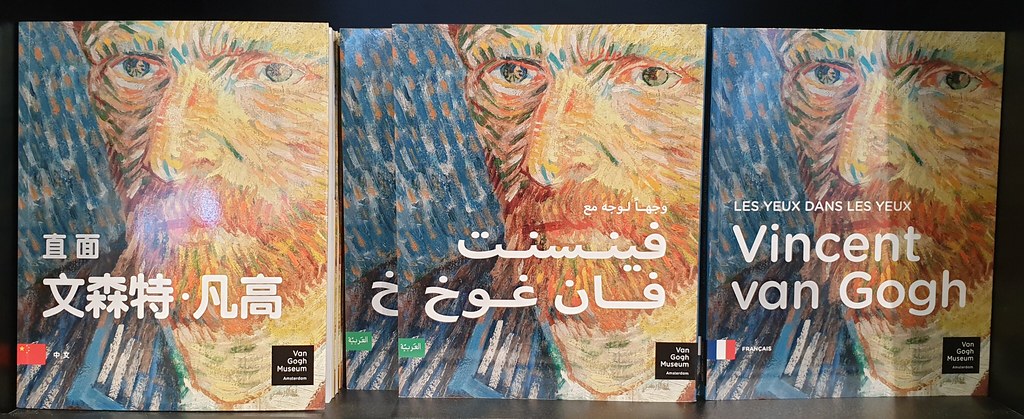

Mary and Jesus’ a painting by Sister Marie Claire. (Picture courtesy: SMMI Provincialate, Bengalaru)

‘Adivasi Madonna’, a painting by Jyoti Sahi

In his introduction which he titles “Unto All of Us a Child is Born,” Jerry Pinto reminisces how he was surprised when he saw his first live Santa Claus. He was a figure in red that Akbarally’s, Bombay’s first department store, wheeled out around Christmas week. “He was a thin man, not very convincingly padded… seemed to be from my part of the world, someone who would climb up our narrow Mahim stairs and leave something at the door for us at three or four a.m., then take the local back to his regular job as a postman or seller of second-hand comics. The man in the cards and storybooks preferred London and New York. And a lot of snow. … Today, it is almost a cliché to say that Christmas, like every other festival, is hostage to the market.”

The other editor, Madhulika Liddle in her introduction “Christmas in Many Flavours” states, “According to the annals of the Mambally Royal Biscuit Factory bakery in Thalassery, Kerala, its founder Mambally Bapu baked the first Christmas cake in India”. It was way back in 1883, at the instance of an East India Company spice planter he set about trying to create a Christmas cake. Liddle wondered what that first Christmas cake tasted like; how close it was to the many thousands of cakes still baked and consumed at Christmas in Kerala? She also writes about the situation in India, where instead of wholesale and mindless importing of Christmas ideas, the people have been discerning enough to amalgamate all our favourite (and familiar) ideas of what a celebration should be and fit them into a fiesta of our own.

Images from Indian Christmas: Essays, Memories, Hymns: dressed up as Santa Claus leave for school in Punjab. (Picture courtesy: Ecocabs,Fazilka).

There are several other aspects of Christmas celebrations too. The Christmas bazaars are now increasingly fashionable in bigger cities. The choral Christmas concerts and Christmas parties are big community affairs, with dancing, community feasts, Christmas songs, and general bonhomie. Across the Chhota Nagpur area, tribal Christians celebrate with a community picnic lunch, while many coastal villages in Kerala have a tradition of partying on beaches, with the partying spilling over into catamarans going out into the surf. In Kolkata’s predominantly Anglo-Indian enclave of Bow Bazar, Santa Claus traditionally comes to the party in a rickshaw, and in much of northeast India, the entire community may indulge in a pot-luck community feast at Christmas time. Thus Liddle states:

“Missionaries to Indian shores, whether St Thomas or later evangelists from Portugal, France, Britain, or wherever brought us the religion; we adopted the faith, but reserved for ourselves the right to decide how we’d celebrate its festivals.”

Apart from their separate introductions, the editors have collated twenty-seven entries of different kinds, each one more interesting than the other, that showcase the richness and variety of Christmas celebrations across the country. Though Christianity may have come to much of India by way of missionaries from Europe or America, it does not mean that the religion remained a Western construct. Indians adopted Christianity but made it their own. They translated the Bible into different Indian languages, translated their hymns, and composed many of their own. They built churches which they at times decorated in their own much-loved ways. Their feasts comprised of food that was often like the ones consumed during Holi or Diwali.

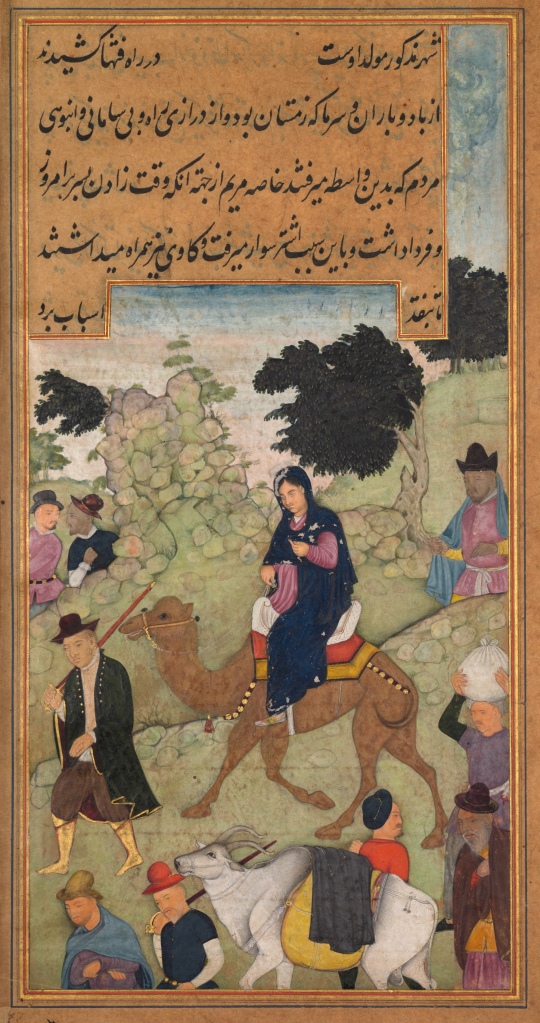

Thus, Christmas in India turned to a great Indian festival that highlighted the syncretism of our culture. Damodar Mauzo, Nilima Das, Vivek Menezes, Easterine Kire, Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, Nazes Afroz, Elizabeth Kuruvilla, Jane Borges and Mary Sushma Kindo, among others, write about Christmas in Goa, Nagaland, Kerala, Jharkhand, Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai, Shillong and Saharanpur. Arul Cellatturai writes tender poems in the Pillaitamil tradition to the moon about Baby Jesus, and Punjabi singers compose tappe-boliyan about Mary and her infant. There are Mughal miniatures depicting the birth of Jesus, paintings by Jyoti Sahi and Sister Claire inspired by folk art, and pictures of Christmas celebrations in Aizawl, Bengaluru, Chennai and Kochi and these visual demonstrations enrich the text further.

Seventeenth-century painting depicting Mary and Joseph travelling to Bethlehem. From a Mir’at al-quds of Father Jerome, 2005, Cleveland Museum of Art. (Wikimedia Commons)

‘Mother Mary and Child Christ’. Mid-eighteenth century, late Mughal, Muhammad Shah period. National Museum of India, New Delhi (Wikimedia Commons)

Interestingly, the very first entry of this anthology is an excerpt from the final two sections of one of Rabindranath Tagore’s finest long poems, inspired by the life of Jesus Christ. Tagore wrote the poem “The Child” in 1930, first in English and translated it himself into Bengali the following year, titling it “Sishutirtha.” But many years even before that, every Christmas in Santiniketan, Tagore would give a talk about Christ’s life and message. Speaking on 25 December 1910, he said:

“The Christians call Jesus Man of Sorrow, for he has taken great suffering on himself. And by this he has made human beings great, has shown that the human beings stand above suffering.”

India celebrates Christmas with its own regional flair, its own flavour. Some elements are the same almost everywhere; others differ widely. What binds them together is that they are all, in their way, a celebration of the most exuberant festival in the Christian calendar.

Apart from the solemnity of the Church services, there is a lot of merrymaking that includes the food and drink, the song and dance. The songs often span everything from the stirring ‘Hallulujah Chorus’ to vibrant paeans sung in every language from Punjabi to Tamil, Hindi to Munda, Khariya and Mizo tawng.

Among the more secular aspects of Christmas celebrations are the decorations, and this is where things get even more eclectic. Whereas cities and towns abound in a good deal of mass decorating, with streets and public places being prettied up weeks in advance, rural India has its own norms, its own traditions. Wreaths and decorated conifers are unknown, for instance, in the villages of the Chhota Nagpur region; instead, mango leaves, marigolds and paper streamers may be used, and the tree to be decorated may well be a sal or a mango tree. Nirupama Dutt tells us how since her city had no firs and pines, she got her brother’s colleague to fetch a small kikar tree as kikars grew aplenty in the wild empty plots all over Chandigarh. In many entries we read about how Christmas decorations were rarely purchased but were cleverly constructed at home.

A very integral part of the Christmas celebrations of course is music. In many Goan Catholic neighbourhoods, Jim Reeves continued to haunt the listeners in his smooth baritone: “I’ll have a blue Christmas without you/ I’ll be so blue thinking about you/ Decorations of red on a green Christmas tree/ Won’t mean a thing, dear, if you’re not here with me.” Simultaneously, the words and music of “A Christmas Prayer” by Alfred J D’Souza are as follows: “Play on your flute/ Bhaiyya, Bhaiyya/ Jesus the saviour has come./ Put on your ghungroos/ Sister, Sister/ Dance to the beat of the drums!/ Light up a deepam in your window/ Doorstep, don with rangoli/ Strings of jasmine, scent your household/ Burn the sandalwood and ghee,/ Call your neighbour in, smear vermillion/ Write on his forehead to show/ A sign that we are one/ Through God’s eternal Son/ In friendship and in love ever more!/ Ah! Ah!” But the most popular Christmas song was of course “Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way….”

In “Christmas Boots and Carols in Shillong”, Patricia Mukhim tells us how the word ‘Christmas’ triggers a whole host of activities in Meghalaya and other Northeastern states that have a predominantly Christian population. Apart from cleaning and painting the houses, everything looks like fairyland during Christmas, a day for which they have been waiting for an entire year. She particularly mentions the camaraderie that prevails during this time:

“Christmas is a time when invitations are not needed. Friends can land up at each others’ homes any time on Christmas Eve to celebrate. Most friends drop by with a bottle of wine and others pool in the snacks and the party continues until the wee hours of morning. It’s one day in the year when the state laws that noise should end at 10 p.m. is violated with gay abandon. …Shillong [is] a very special place on Planet Earth. Everyone from the chief minister down can strum the guitar and has a voice that could put lesser mortals to shame. And Christmas is also a day when all VIPism and formalities are set aside. You can land up at anyone’s home and be welcomed in. It does not matter whether someone is the chief minister, a top cop, or the terrifying headmistress of your school.”

One very significant common theme in all the multifarious entries is the detail descriptions provided on food, especially the makeshift way Christmas cakes are baked in every home and the Indian way meat and other specialties are being prepared on the special day. There are several entries that give us details about the particular food that was prepared and consumed at the time along with actual recipes about baking cakes. “Christmas Pakwan[1]” by Jaya Bhattcharji Rose, “The Spirit of Christmas Cake” by Priti David, and “Armenian Christmas Food in Calcutta” by Mohona Kanjilal need special mention in this context. Liddle in her introduction wrote:

“Our Christmas cakes are a reflection of how India celebrates Christmas: with its own religious flair, its own flavour. Some elements are the same almost everywhere; others differ widely. What binds them together is that they are all, in their way, a celebration of the most exuberant festival in the Christian calendar.”

Later in her article “Cake Ki Roti at Dua ka Ghar[2],” the house where they lived in Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh, she wrote how her parents told her that ‘bajre ki tikiyas’, thin patties made of pearl millet flour sweetened with jaggery, used to be a staple at Christmas teatime at Dua ka Ghar[3], though she has no recollection of those. She of course vividly recalls the ‘cake ki roti’. This indigenisation of Christmas is something that’s most vividly seen in the feasting that accompanies Christmas celebrations across the country. While hotels and restaurants in big cities lay out spreads of roast turkey (or chicken, more often), roast potatoes and Christmas puddings, the average Indian Christian household may have a Christmas feast that comprises largely of markedly regional dishes.

In Kerala, for instance, duck curry with appams is likely to be the piece de resistance. In Nagaland, pork curries rich in chillies and bamboo shoots are popular, and a whole roast suckling pig (with spicy chutneys to accompany it) may hold centre stage. A sausage pulao, sorpotel and xacuti would be part of the spread in Goa, and all across a wide swathe of north India, biriyanis, curries, and shami kababs are de rigueur at Christmas.

This beautifully done book, along with several coloured pictures, endorses the idea of religious syncretism that prevails in India. As a coiner of words, Nilima Das came up with the idea that ‘Christianism’ in our churches is after all, a kind of ‘Hinduanity’ (“Made in India and All of That”). This reviewer feels guilty of not being able to mention each of the unique entries separately that this anthology contains, so it is suggested that this is a unique book to enjoy reading, to possess, as well as to gift anyone during the ensuing Christmas season.

[1] Cuisine

[2] Cake bread

[3] Blessed House

Somdatta Mandal, critic, academic and translator, is a former Professor of English at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India.

Click here to access an excerpt of Tagore’s The Child

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International