He sees a barrier where soldiers stand

with rifles drawn, encroachers kept at bay.

A migrant child who holds his mother's hand

— LaVern Spencer McCarthy, Are We There Yet?

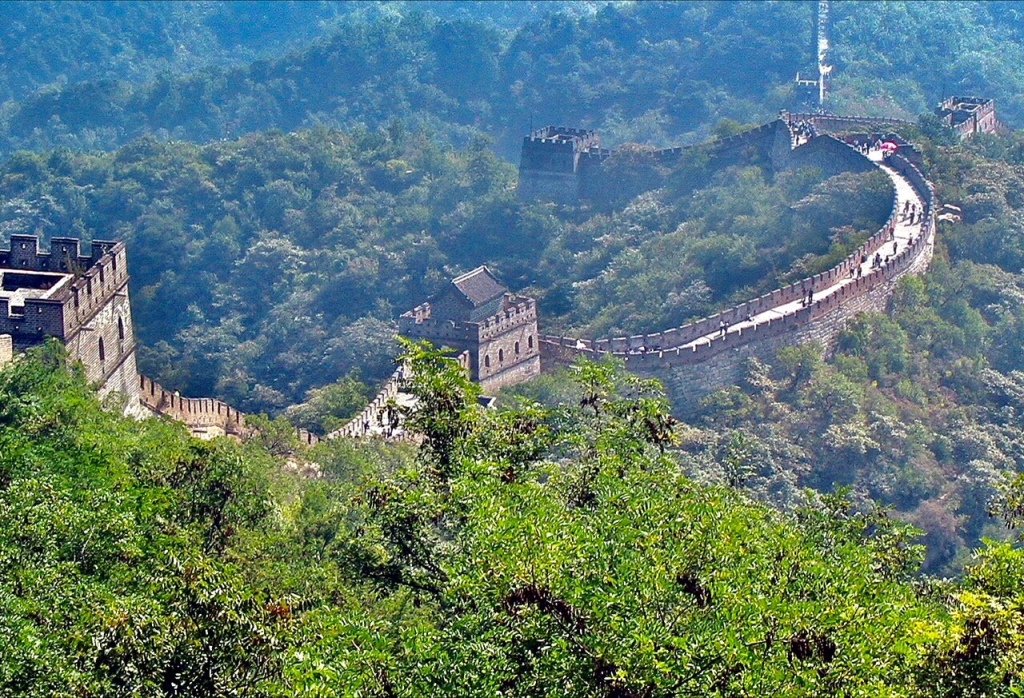

There was a time when humans walked the Earth crossing unnamed landmasses to find homes in newer terrains. They migrated without restrictions. Over a period of time, kingdoms evolved, and travellers like Marco Polo talked of needing permissions to cross borders in certain parts of the world. The need for a permit to travel was first mentioned in the Bible, around 450BCE. A safe conduct permit appeared in England in 1414CE. Around the twentieth century, passports and visas came into full force. And yet, humanity had existed hundreds of thousand years ago… Some put the date at 300,000!

While climate contingencies, wars and violence are geared to add to migrants called ‘refugees’, there is always that bit of humanity which regards them as a burden. They forget that at some point, their ancestors too would have migrated from where they evolved. In South Africa, close to Johannesburg is Maropeng with its ‘Cradle of Humanity’, an intense network of caves where our ancestors paved the way to our evolution. The guide welcomes visitors by saying — “Welcome home!” It fills one’s heart to see the acceptance that drips through the whole experience. Does this mean our ancestors all stepped out of Africa many eons ago and that we all belonged originally to the same land?

And yet there are many restrictions that have come upon us creating boxes which do not allow intermingling easily, even if we travel. Overriding these barriers is a discussion with Jessica Mudditt about Once Around the Sun: From Cambodia to Tibet, her book about her backpacking through Asia. Documenting a migration more than a hundred years ago from Jullundur to Malaya, when borders were different and more mobile, we have a conversation with eminent scholar and writer from Singapore, Kirpal Singh. Telling the story of another eminent migrant, a Persian who became a queen in the Mughal Court is a lyric by Nazrul, Nur Jahan, translated by Professor Fakrul Alam from Bangla. Ihlwha Choi has self-translated his own poem from Korean, a poem bridging divides with love. Fazal Baloch has brought to us some exquisite Balochi poems by Munir Momin. Tagore’s poem, Okale or Out of Sync, has been translated from Bengali to reflect the strange uniqueness of each human action which despite departing from the norm, continue to be part of the flow.

Among our untranslated poetry is housed LaVern Spencer McCarthy’s voice on the plight of migrants of the current times. Michael Burch gives us poems for Dylan Thomas. We have a plethora of issues covered in poetry ranging from love to women’s issues, even an affectionate description of his father by Shamik Banerjee. Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Kumar Sawan, Prithvijeet Sinha, Gregg Norman, Anushka Chaudhary, Wayne Russell, Ahmad Rayees, Ivan Ling, Ayesha Binte Islam and many more add verve with their varied themes. Rhys Hughes has shared a poem on a funny sign he photographed himself.

We have a tongue in cheek piece from Devraj Singh Kalsi on traveling in a train with a politician. Uday Deshwal writes with a soupçon of humour as he talks of applying for jobs. Snigdha Agrawal brings to us flavours of Bengal from her past while Ratnottama Sengupta muses on the ongoing wars and violence as acts of terror in the same region and looks back at such an incident in the past which resulted in a powerful Bengali poem by Tarik Sujat. Kiriti Sengupta has written of a well-known artist, Jatin Das, a strange encounter where the artist asks them to empty fully even a glass of water! Ravi Shankar weaves in his love for books into our non-fiction section. Recounting her mother’s migration story which leads us to perceive the whole world as home is a narrative by Renee Melchert Thorpe. Urmi Chakravorty takes us to the last Indian village on the borders of Tibet. Taking us to a Dinosaur Museum in Japan is our migrant columnist, Suzanne Kamata. Her latest multicultural novel, Cinnamon Beach, has found its way to our book excerpts as has Flanagan’s poetry collection, These Many Cold Winters of the Heart.

In reviews, Somdatta Mandal has written about an anthology, Maya Nagari: Bombay-Mumbai A City in Stories edited by Shanta Gokhale and Jerry Pinto. Rakhi Dalal has discussed a translation from Konkani by Jerry Pinto of award-winning writer Damodar Mauzo’s Boy, Unloved. Basudhara Roy has reviewed Trailokyanath Mukhopadhyay’s Tales of Early Magic Realism in Bengali, translated by Sucheta Dasgupta. Bhaskar Parichha has introduced us to The Dilemma of an Indian Liberal by Gurcharan Das, a book that is truly relevant in the current times in context of the whole world for what he states is a truth: “In the current polarised climate, the liberal perspective is often marginalised or dismissed as being indecisive or weak.” And it is the truth for the whole world now.

Our short stories reflect the colours of the world. A fantasy set in America but crossing borders of time and place by Ronald V. Micci, a story critiquing social norms that hurt by Swatee Miittal and Paul Mirabile’s ghost story shuttling from the Irish potato famine (1845-52) to the present day – all address different themes across borders, reflecting the vibrancy of thoughts and cultures. That we all exist in the same place and have the commonality of ideas and felt emotions is reflected in each of these narratives.

We have more which adds to the lustre of the content. So, do pause by our content’s page and enjoy the reads!

I would like to thank all our team without who this journal would be incomplete, especially, Sohana Manzoor, for her fabulous artwork. Huge thanks to all our contributors who bring vibrancy to our pages and our wonderful readers, without who the journal would remain just part of an electronic cloud… We welcome you all to enjoy our June issue.

Wish you happiness and good weather!

Thank you all.

Mitali Chakravarty

Click here to access the content’s page for the June 2024 Issue.

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.