Narrative and photographs by Suzanne Kamata

Many years ago, when my children were small and I was working on my first-to-be-published novel Losing Kei, I joined an online writing group made up of members of the Association of Foreign Wives of Japanese. Since I live off the beaten track, on the island of Shikoku, this group was a godsend for me. Not only was I able to connect with non-Japanese women raising biracial kids in a supposedly homogenous country, but I could also connect with others writing in English.

I ultimately finished my novel. I was not the only member of this group who went on to publish books. In addition to writing and publishing, another wonderful thing that came out of this now defunct virtual community was the Japan Writers Conference, which was first held in 2008. One of the members, poet and writer Jane Joritz-Nakagawa, whose most recent book is the searing LUNA (Isobar Press, 2024), proposed a grassroot gathering of writers in Japan. There would be no keynote speaker, no fees for participants, and no payments for presenters. We would just get together and share our writing and our expertise.

Another member, Diane Hawley Nagatomo, who recently published her second novel, Finding Naomi (Black Rose Writing, 2024) after an illustrious career in academia, volunteered to host the initial conference at her university. Chanoyu University, in Tokyo, is famously the institution attached to the kindergarten attended by the Japanese royal family. It was also the site of the first Japan Writers Conference.

Since then, the conference has been held at various universities and colleges around the country, including in Okinawa, Hokkaido, Kyoto, Iwate, and at Tokushima University, hosted by me in 2016. Over the years, many notable speakers have appeared, such as Vikas Swarup, whose novel Q & A became the film Slumdog Millionaire, popular American mystery writer Naomi Hirahara, and Eric Selland, poet and translator of The New York Times bestseller The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide. The list goes on and on.

This past year, the conference was held not at a university, but at the Futaba Business Incubation and Community Centre.

When I told my husband that I was going to Futaba, he looked it up on a map.

“That’s in the exclusionary zone,” he said, somewhat alarmed.

Indeed, the conference would be held on the coast in Fukushima Prefecture, not too far from the site of the nuclear power plant which was hit by a tsunami in 2011. For years, there have been concerns about radiation, however the area is staging a comeback. The host of this year’s conference would be the Futaba Area Tourism Research Association, an organisation committed to “promoting tourism and land operations, inviting people to rediscover the charms of Fukushima’s coastal areas. The company’s mission is to bring people worldwide to this unique place that has recovered from a nuclear disaster.”

“I don’t think they would hold the conference there if it wasn’t safe,” I told him.

The JWC website reported that although the town had been evacuated after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, evacuation orders had been lifted for about 10% of the town on August 30, 2022. Decontamination efforts are still underway. New homes are being built, new businesses are emerging, and the annual festival Daruma-Ichi resumed in 2023. The areas hosting the JWC had been deemed safe, “with radiation levels regularly monitored and within acceptable limits.” I reserved a room at the on-site ARM Hotel and went ahead with my plans.

Getting to Futaba from my home in Tokushima took all day. I got up before the sun and took a bus, a plane, then a succession of trains. As I got closer to my destination, I noted the absence of buildings along the coast. I tried to imagine the houses that might have been there before the grasses had gone wild. Later, the appearance of earth-moving equipment suggested future development.

From the nearly deserted train station, I took a bus, and then lugged my suitcase to the hotel’s registration desk. There was nothing around besides the convention center and the hotel. I saw a very tall breakwater, blocking my view of the ocean. I felt as if I were on the edge of the world.

The evening before the conference began, I had dinner at the hotel restaurant, where I met up with some writers I had gotten to know at past conferences. Ordinarily, we might have moved on to a bar to continue our literary discussions, but after the restaurant closed at eight, there was nowhere else to go. There was some talk of going to the beach. A few of us went out into the night and sat on the seawall, sipping Scotch from paper cups, and talking under the stars. At one point, we contemplated the waves below, all those who were washed out to sea and remained missing.

The conference began the following morning. I was amazed that, in spite of the effort that it had taken to get there, presenters had come from all over the world – a Syrian poet who was based in Canada, a poet from Great Britain, a Japanese writer and translator who lived in Germany, a Tunisian writer and motivational speaker who’d flown in from UAE.

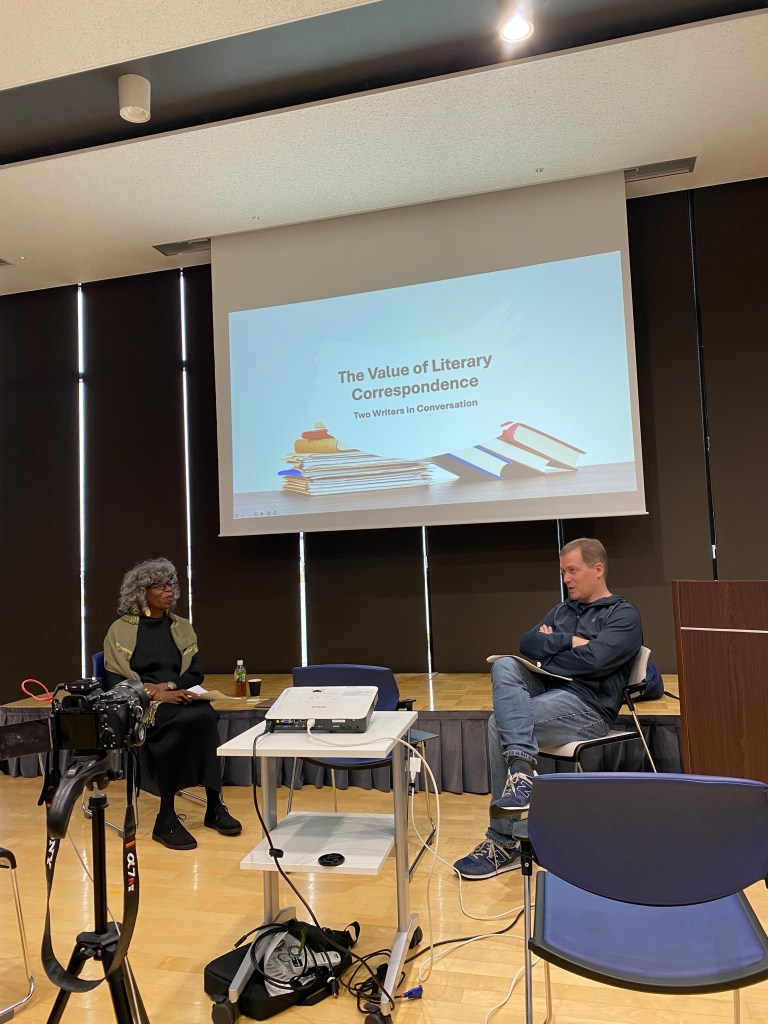

I gave a presentation on writing for language learners and shared my haiku in another session. Others presented on a variety of topics including literary correspondence, storytelling and tourism, climate fiction, and writing the zuihitsu[1]. In between sessions, I caught up with old friends and met new ones. On Saturday night, there was a banquet with bentos featuring delicacies such as smoked duck, mushroom rice, and salad with Hokkigai clams.

In retrospect, it was especially meaningful to attend the conference in Futaba, and to feel that we were able to play some small part in the rejuvenation of the area. It was also exciting to interact with writers who came from so far away. Although it’s still very much a grassroots event, it has become truly international.

(To find out about the next Japan Writers Conference and sign up for the mailing list, go to https://japanwritersconference.org/)

[1] A loose collection of personal essays

Suzanne Kamata was born and raised in Grand Haven, Michigan. She now lives in Japan with her husband and two children. Her short stories, essays, articles and book reviews have appeared in over 100 publications. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize five times, and received a Special Mention in 2006. She is also a two-time winner of the All Nippon Airways/Wingspan Fiction Contest, winner of the Paris Book Festival, and winner of a SCBWI Magazine Merit Award.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International