Book Review by Somdatta Mandal

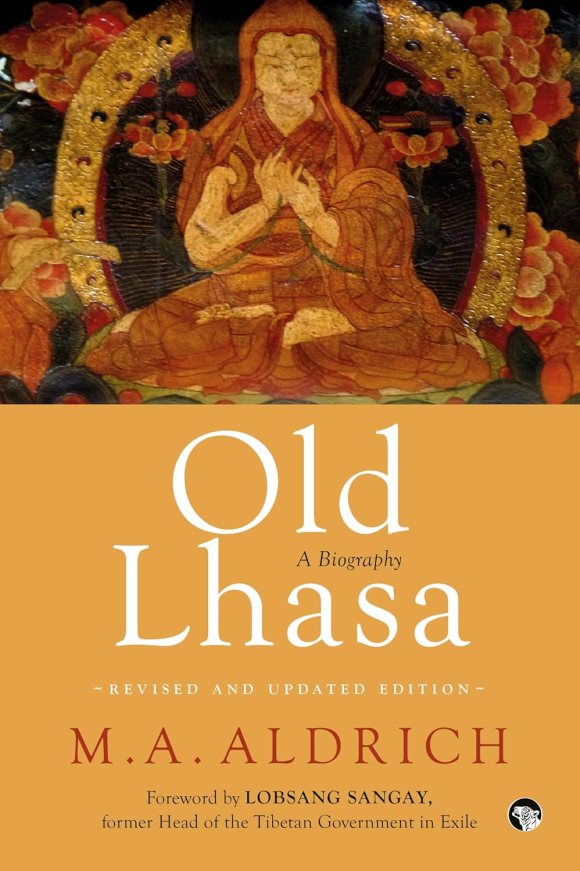

Title: Old Lhasa: A Biography

Author: M.A. Aldrich

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Book

“Contrary to common perceptions, Lhasa is not forbidden to outsiders” – M.A.Aldrich

Old Lhasa: A Biography, (a revised edition published in 2025 for the South Asian market of a book originally published in 2023), is a voluminous 615-page book that combines historical research, travel writing, religion, and culture to offer a comprehensive account of Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet. The author, M. A. Aldrich, is a lawyer who has lived and worked in Asia since the 1990s and had earlier published books on cities like Peking and Ulaanbaatar. Written on the basis of his multiple trips to Lhasa and its surroundings (the last one as late as September 2024), he is happy to discover that Old Lhasa has stood the test of time and still accurately captures the sight, sounds, and feelings of the city and foreigners can wander about freely without a minder so long as their papers are in order. As this book slowly emerged, it grew into both a portrait of the history and culture of that city as well as a serviceable guidebook for readers who are able to go to Tibet when political and regulatory circumstances permit.

Aldrich paints an intricate portrait of Lhasa, a storied city and its history, by giving us the evolution of how the Tibetan script came to be, with inspiration from ancient India and at the same time livens up the narrative with humorous anecdotes, interesting legends and charming fables that makes this book blend many genres into one. Divided into 49 chapters and enriched with several maps and black and white photographs, the chronological narration rightfully begins with the first chapter titled ‘Prelude to Lhasa’ where we are told that with Lhasa as the geographical focal point of their faith, Tibetans believe the dharma[1] has always been connected to their country. He begins the journey in the seventh century during the final moments of the life of Buddha, mentions specific Buddhist virtues such as compassion, wisdom, and benevolent power, among other essential qualities for the path to awakening. For Tibetan followers of the dharma, the history of Tibet is the history of the Bodhisattva of Compassion, which is simultaneously woven into the story of Lhasa.

In the 1920s, when Tibet enjoyed its greatest freedom from outside interference in the modern era, Lhasa had a population of only around twenty-five thousand. It was divided into two districts: one that is now the Old Town, with its seventh-century Jokhang Temple (or, more simply, the “Jokhang,” meaning the “House of the Lord”) at its centre; and the other being Shol Village, which is at the foot of Marpo Ri (Red Mountain). These administrative districts were divided by a north-south boundary that ran through the Turquoise Bridge, another structure dating to the seventh century. The Old Town was not much larger than two- or three-square kilometers, while Shol was even tinier. The residents of Lhasa at that time took immense pride in the religious heritage of their city. Nearly every luminary in Tibetan history had come to Lhasa because of the importance of the Jokhang as the focal point from which Tibetan civilization evolved and expanded. No other city could rival it.

Lhasa grew organically outward in concentric circles. Around 1160, a monk built the Nangkhor, a pilgrim’s circuit (korlam) directly adjacent to the inner sanctum of the Jokhang, so that devotees could practice the religious ritual of circumambulation. It is from this kernel that the boundaries of Old Lhasa came into existence. By the 14th century, Lhasa was enclosed within the Barkhor, a kilometre-long korlam circling the temple and a monastery among other buildings. By the 1650s, Lhasa’s outer limits had been expanded to the Lingkhor, a ten-kilometre pilgrimage route. And so, the boundaries of the city remained until recently.

Lhasa’s significance also drew heavily upon the nearby presence of government buildings and monastic sects of learning. The Potala Palace, with its superb representation of Tibetan architecture, is a massive and dazzlingly beautiful fortress-like monastery that had been the residence of the Dalai Lama and the seat of the Tibetan government since 1648. Three monasteries outside the city were centres of the so-called Yellow Hat or Gelukpa School of Tibetan Buddhism, preserving a venerable tradition of scholasticism and monastic training that had been imported to Tibet from the universities at Nalanda, Odantapuri and Vikramshila in Northern India. Daily life in early 20th century Lhasa was mostly grounded in religion for both the laity as well as the clergy. The Lhasa calendar year revolved around a sequence of religious festivals that tracked the flow of one month into another in a never-ending cycle of faith and devotion. Though religion permeated society, Lhasa was not an “other-worldly” place. In 1951, when the People’s Liberation Army marched into Lhasa behind portraits of Chairman Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Liu Shaoqi, the days of the city with its self-administered culture were numbered. During the 1959 Tibetan Uprising, the Chinese Communist Party reacted to the civil unrest as if Tibet should be taught a lesson. The Party continues to do so despite brief intermittent periods of slightly relaxed policies. Though Chinese modernity has been imported wholesale into Lhasa, the author opines that Old Lhasa is still there in its people who maintain their centuries-old faith and customs. One just needs to know where and how to look.

In the Prologue, Aldrich had confessed that this is not a “serious book” about Lhasa as the term is understood within the narrow confines of modern academia, since its objective is only to share what he had learned about Lhasa with simpaticos. His audience is the general reader or armchair traveller with a basic understanding of the tenets of Buddhism and the broad outlines of Asian history. He does not go into great depth on religious theory, and he hopes his views might also be of interest to Tibetans who have come of age in the diaspora and are curious about what a non-Tibetan thinks of this fabled city. He attempts to avoid the excessive solemnity and despair that attends much writing about Tibet. It is not that he is ignorant of ongoing atrocities and the appallingly cruel policies of the Party, but he has no doubt Tibet will have a renaissance. He opines Tibetans will overcome the current dark cycle just as they have overcome other bleak phases in their history.

In conclusion, it can be said that even after reading it thoroughly and enjoying it, this book as the author rightly states, “will nudge readers to learn more about Tibet and Tibetan culture.” Also, as Dr. Lobsong Sangay, former head of the Tibetan Government in Exile, rightfully mentions in the ‘Foreword’

, “Though the story of Tibet is an ongoing tale of tragedy, it also is a tale of the human spirit and the resilience of the Tibetan people. …this book is a window for seeking genuine access that will help you make meaningful discoveries of your own, whether you are physically travelling through the streets of Lhasa or traveling through the pages of this book far away from Lhasa.”

[1] faith

Somdatta Mandal, critic and translator, is a former Professor of English at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International