Professor Fakrul Alam writes of libraries affected by corporate needs… With this essay, we hope to launch a discussion on libraries as we knew them and the current trends…

Dhaka, 2003

Where have all those libraries gone?

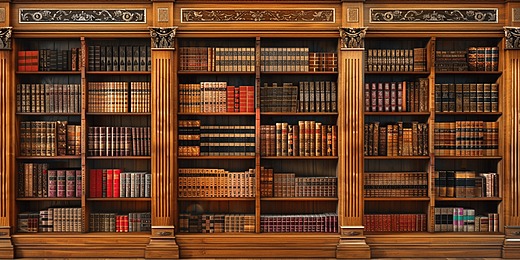

Back in the ‘70s, in-between classes, adda[1], and sports, I used to spend most of my time in the USIS[2], British Council, or Dhaka University libraries. I would go to USIS for its collection of magazines and fiction, and to the Dhaka University Library for almost everything else. Despite the dust, the load shedding, the noise, the frequent closures of the university and the missing pages within the books, it was a splendid place for both adda and study. Some of my friends and acquaintances lamented that somehow, I had lost interest in “fielding” and had turned into a bookworm, but every book that I read made me thirst for more treasures of English literature. And then there was the British Council Library.

Perhaps memory always rose-tints the past, but it seems to me now that it was the friendliest part of the city then. The lush green lawn and the open spaces that surrounded the library, the access to stacks and stacks of books, the periodicals that you could leaf through, anything from the latest cricket news to reviews of books, the abundantly stocked reference section that was a source of special delight for me, the rows after rows of books that you could explore—here was God’s plenty! The Dhaka University Library had no doubt a much richer collection, but inside the British Council Library you could occasionally experience the bibliophile’s ultimate thrill: leafing through yellowing pages of a fairly old book, only to set it aside for another one; or merely reading surreptitiously through a page or two, secure in the knowledge that not all books are to be swallowed, chewed, and digested, that at least a few are to be tasted, and that was what the British Council Library was for! I would take a book or a periodical on a lazy day, sit down in one of the chairs, and then dream away, secure in the feeling that “there is no Frigate like a Book/ To take us lands away/ Nor any Coursers like a Page/ Of prancing Poetry.”

Everything about the British Council of this period seemed to be inviting. You got to know the staff after a few visits and they were all very friendly. I was still a student when I was on a “first-name basis” with the expatriate assistant representatives and librarians. In the middle of the decade, though only a lecturer at Dhaka University, I could claim the Librarian, Graham Rowbotham, to be a dear friend. In retrospect and especially compared to the library decor and staff now, everybody and everything associated with the library seemed to be amateurish in a way that was endearing and conducive to aimless browsing and long hours of lounging. Book of verse or criticism in hand, I loved spending my mornings here, although “thou” would be a few desks away, and to be glanced furtively in an essentially one-way traffic!

New books kept coming fairly regularly and were ordered by people of catholic tastes and wide-ranging interests. But most importantly, membership was cheap. I can’t remember what the membership fees were, but it must have been ridiculously low since even in those cash-strapped days I never seemed to have been bothered about renewing my membership from year to year. And yet you didn’t have to be a member to go in and browse, although I always preferred to be one so that I could always have books to take away and read at home.

Returning to Bangladesh after six years in Canada, I found the British Council of the ’80s not that different from the inviting, relaxed place I knew in the ’70s, although by now incoming books had slowed down to a trickle. Towards the end of the decade, I think, the library added a video section, but, on the whole, the Council seemed to be cutting back on everything. I had also heard that the library was going to be restructured; apparently, the “Iron Lady” was bent on making the British Council less of a burden on the British economy and more of a self-sustaining, income-generating unit.

But the full effect of the restructuring of the British Council into a self-sustaining, charitable organisation was obvious only by the middle of the ’90s. The Thatcherite assault on the arts, a heightened British concern with security after the Gulf War, and unrest in Dhaka University all must have played their parts, for in 1995 the British Council decided that they would leave the campus for the security of the Sheraton Annex.

The first casualty of what was surely an ill-conceived decision, like USIS’s move to Banani was the British Council’s wonderful collection of books. Row after row of books were given away for free. Indiscriminately. Thoughtlessly. Even some reference books and bound periodicals were distributed gratis since it was felt the Sheraton British Council would have very little space.

Thankfully, the British Council abandoned its move to the Sheraton, but the Fuller Road library never recovered from the book-giving spree. Instead, the library was redesigned to give it a contemporary feel on the outside as well as the inside, security was beefed up, and everything about the library redone to give it a “new”, packaged look.

A cyber centre was installed to make you feel that the ambience was au courant, and impressive graphics-brightened the walls. But what is a library without stacks and stacks of books? The British Council was always the repository of the best in British culture, but this one seemed to be as anaemic as the foreign policy of present-day Britain and nowhere representative of the nation’s past cultural glory. Indeed, where were the Booker Prize winners, the Nobel laureates, the Poetry Book Society choices, London Magazine, Granta, The New Left Review, The London Review of Books? Where were the bibliographies, the reference books that you could use to track an idea or pursue a stray thought to an ever-widening world, so that even within the confines of a library you “felt like some watcher of the skies/ when a new planet swims into his ken?”

The British Council has leased the best piece of property in town from the University of Dhaka. And what does it offer the university’s students? Forced to generate revenues for its upkeep, it had become, as my dear friend put it so memorably, the New East India Company, making money any which way it is able to. Thus, the Council was now more bent on offering exorbitantly-priced language courses and all sorts of examination services, trading on its Englishness and cashing in on the dismal state of our educational system set back by excesses of linguistic nationalism, than on stocking books that represented the best in British culture and that could be made available to the largest group of people. Library fees are ridiculously high—which middle class family can afford to make its children members at Tk 1,300 a year? And entry to the library itself is restricted—you have to be a member to browse! In fact, everything about the present British Council Library reinforces the feeling that it serves almost exclusively two groups of people: the upper class of Dhaka and people desperate about going to Britain for higher studies!

Significantly, the British Council Library now has remade itself as the Library and Information Services. What services? I stopped becoming a member in 1998 when I realised that the membership fees, which I could barely afford even then (the current fees are Tk 650 a year!), were entitling me to diminishing returns every year since the books and most of the periodicals I wanted to read were not there. The year I quit my membership after I had requested the library to procure a book on Burke and India for a research project but, despite repeated reminders to the librarian, that book never came (and I thought that they would listen to a professor of English literature at Dhaka University). The reference section was no longer stocking current bibliographies and sources of information about the world of books.

When I decided to write this piece, I thought in all fairness I should spend some time checking out the Library’s current state before I started critiquing its current library policy. To my dismay, I found that things had gone from bad to worse in the last few years. What services? There is now left only one shelf of literature books and another one devoted to reference items. The library looks pretty, and everything is neatly arranged but why does it remind me of the artificial, vacuous smile of the catwalk beauty? No doubt in line with modern concepts of interior design the library has more space than ever before, but all I see in it is emptiness! Yes, it is smartly done and for the smart people, but where is the world of knowledge in all this?

As my colleague pointed out to me in a note, “What services? How can the young come and request books they don’t know about? Knowledge comes from browsing the shelves, from looking at books and authors you have never seen before, and then you pick it up and read a new author, and perhaps you find a lifelong favourite and your mental landscape changes and that’s what a library’s function is, to widen, to broaden, to expose minds to superior stuff, not provide some crap ‘services’, some videos, some paper hangings, and then have the gall to call it ‘progress’ or ‘keeping up with the times’ or whatever!”

I should add that I have no real problem with the British Council cashing in on the O and A level market and IELTS[3] examinations, but I can’t figure out why it can’t plow back more of its surely substantial profits into establishing a proper library instead of the Fuller Road scam that now calls itself one. Let it charge the people who can afford its outrageously-priced language courses all it wants to, but why can’t it lower library fees so that anybody who wants to can use the library facilities, can browse and read in the library without having to pay anything? I am aware that the British Council is a registered charity and believe that it is supposed to spend its gains here, but can’t it become a leaner operation so that it can beef up its library services? Shouldn’t charity begin at home?

Our libraries have become shadows and shells of their former selves, and it is time we started to ask ourselves a very simple question: what exactly is a good library? And don’t we owe our children and ourselves at least one library?

(Adapted from the essay, ‘The British Council Library: The New East India Company?’ Published on November 8, 2003 in Daily Star)

[1] Casual sessions of tête-à-tête

[2] United States Information Service Library

[3] Internation English Language Testing System

Fakrul Alam is an academic, translator and writer from Bangladesh. He has translated works of Jibonananda Das and Rabindranath Tagore into English and is the recipient of Bangla Academy Literary Award (2012) for translation and SAARC Literary Award (2012).

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International