By Paul Mirabile

I met Gustav Beekhof twice whilst travelling in North Africa, once in Tunisia on the island of Djerba, and then in Algeria when I emerged from the desert after spending about seven months living amongst the Touregs.

Gustav was a Dutchman, tall, slender, long blond hair falling to his rounded shoulders. His blue eyes shone like scintillating mountain lakes in the morning sun. He spoke excellent English, French and German, all learned at school but polished and refined ‘on the road’ as he said in his high, nasalised voice.

Over a glass of tea, we spoke about many subjects, he emphasising that the voyager must touch Africa with his or her feet, and not ‘do’ it either in vans or in Land-Rovers as so many ‘doers of Africa do’. Gustav indeed had a whiff of smugness about him.

We split, the cocky Dutchman en route to Morocco, I back into the desert to Tamanarasset. Before leaving, however, he gave me his phone number and insisted that if I ever found myself in Amsterdam I should look him up. He threw back his long blond hair and as he got up to leave, said that he held my friendship in high regard.

Seven years later this was exactly what I did! I had been shuffling between Madrid and Burgundy France as a Flamenco guitarist at Rosario’s dance studios in the mornings and Antonio’s mesón[1] at night, and as a grape-picker at several farms between Dijon and Beaune in Burgundy. Every Autumn I would hitch to Burgundy from Madrid and for a month or so labour in the fields, in the wine-cellars, bottle wine and study oenology with the wine-growers in my spare hours.

The life of a mediocre musician and a seasonal farm labourer made no sense. I needed a change. Was not life a thick forest of possibilities ? One day as I treaded wine in one of the enormous kegs that aligned the cellar of a famous wine-grower, what the Burgundians call ‘piger‘, I suddenly thought of Gustav Beekhof. That night, back in my little room on the farm, I searched through my belongings and found his address. Yes, I would go to Amsterdam for that change.

When my work had finished on the farm I left my guitar with some friends, borrowed a bicycle and cycled up to Holland via Liechtenstein and Belgium, a strenuous journey, given the fact that the bicycle had no gears. I arrived in Amsterdam, thoroughly exhausted, but immediately set out to find my ‘friend’, if I may say so at this point in my narrative.

And indeed I did find him: having telephoned Gustav, that nasalised voice gave me directions to his home. I set off on my bike in search of him. It took me hours as I crossed bridges, turned in and out of little roads and lanes. As I struggled on, I had a strange feeling that Gustav did not know with whom he was speaking over the phone. Be that as it may, I finally found his ‘humble home’ as he merrily said, one of the many barges that float listlessly in the canals that criss-cross Amsterdam. A rather shoddy one at that, but its bohemian appearance did suit the personality of the individual I had met some seven or eight years ago in North Africa, and who was at present standing on the plank that led to the barge from the grassy pavement-bank. He was all smiles. He gestured for me to come ‘aboard’, shook my hand and led me into his ‘humble home’ …

A home that rocked and rolled ever so gently when a barge cruised by. Gustav warned me that to live in a barge one must develop sea-legs. He laughed, and the twinkle in his eye intuited that the Dutchman had no idea with whom he was speaking. I felt rather uncomfortable at first, but this loss of memory seemed not to disturb my host who spread out his long arms as if to engulf all the belongings that swam before my eyes: dozens and dozens of paintings, either framed, rolled up in clusters or on easels covered the uncarpeted ‘bottom deck’ along with hundreds of acrylic paint tubes, whilst more books and documents rose in high stacks against the unpanelled ‘starboard’, barring the grey afternoon light from penetrating two ‘portholes’. Large packages lay on a bunk bed at the ‘stern’. There were no rooms, only a very long and narrow ‘hole’ with a kitchenette at the ‘prow’. Rusting red-painted iron beams horizontally crossed the ‘hull’. Two tables had been placed in middle of this capharnaum[2], one for writing, I presumed, and one for eating ; both had seen better days. The toilet, a cubby hole, was located on ‘portside’ …

I was overwhelmed by the quantity of paintings, some of which I recognised.

“How do you like my prized collection ?” Gustav began. His tone had an undercurrent of secrecy. “I have acquired them at great pains, some are originals, others copies … and a few a result of my own genius.” Modesty was never a quality of Gustav’s personality … not even false modesty !

“But you have a Jasper Johns[3] … a Frans Van Mieris[4] and a Nicolais Astrup[5]!” I rejoined in amazement. They must have cost a fortune. My host shrugged his shoulders.

“Why do you think I live on a rubbishy barge and not in a golden palace, my dear lad ?” He threw back his long blond hair and motioned to the hackney table, where two plates, two forks and two knives had been neatly set. I sat opposite a lovely Laurits Andersen Ring painting: Road in the village of Bunderbrøde. Original or copy ? From the kitchenette Gustav sailed back gingery to the table carrying a large tray of chips ; they were dripping with oil. I put one or two in my mouth and felt sick to my stomach. From a cupboard near the toilet he brought forth a bottle of Jenever which presumedly was to wash down the chips. I looked over to his writing table and observed an open notebook.

“My Waybook,” he laughed. “I’m writing a collection of poems and stories about my voyages in India, Central Asia and Africa. Poems and stories written out ‘on the road’, but here in my barge-solitude, polished to a lacquered lustre.” My host was beaming with self-complacency.

I let Gustav make inroads on that greasy stack of chips whilst I cast cursory glances at those many paintings… “Remember those horrible mosquitoes in Africa ?” he reminisced. “They always bit me … perhaps because my blood is so sweet.” His voice had a fluty tone to it. I nodded perfunctorily.Was his blood sweeter than mine ?

I left about midnight, rather sozzled from all that Jenever.

For the next few days, my Dutch friend took me about Amsterdam, especially to the bars where we would invariably get thoroughly drunk, but also to the countryside on bicycle, gliding by the still standing windmills cranking their sails, the tulip fields in blushing bloom, over a streamlet or two, our bicycles poled over on small barques. One day we stopped near one of those streamlets to indulge in some Gouda and Edam cheese. It was there that Gustav, his mouth full of cheese and bread, made me a proposition which I was to regret for the rest of my living days …

“Listen,” he began, munching merrily, washing down his cheese and bread with a few shots of Jenever. “Since you’re out of work, how about working for me ?” I raised a quizzical eyebrow. He gave me a sly wink. “Don’t worry, it’s not hard labour. I need an itinerant salesman for my paintings. You know, I’m stuck here in Amsterdam and can’t meet the demands of all my clients. I have clients in Italy, Spain, France, England ; all over Eastern Europe, too. You’d be a perfect dealer for me, you know many languages, you have a bit of artistic talent yourself to explain certain niceties, and above all, you’re honest. I know you won’t cheat me.” His grin stretched from ear to ear. A strange grin, plastic-like. “I’ll give you ten percent of the proceeds.” And he had another spot of Jenever.

“Why ten ?”

“Why not ? It’s a number like any other. And don’t forgot, some of those paintings are going for over 8,000 Guilders, even double that in other currencies. What do you think ?” He eyed me fixedly, the deep blue of those two tarns swirling before me like turbulent whirlpools.

It took me three days to think over his proposition, and during those three days, when I visited him, we tramped about Amsterdam’s bars, drinking and conversing. Never once did he enquire about my decision. It was whilst licking off the foam of my Heineken in one of Gustav’s favourite bars, where it was his wont to reach into a drinker’s open poach of tobacco, serve himself a good pinch and roll a cigarette without ever asking permission, a rite that he alone exercised at the counter, that I decided to accept his offer. “Fifteen percent !” I added. He winced at first, but that mask slowly transformed into a broad smile. We shook hands and the deal was sealed. He ordered another round for us whilst pinching a bit more tobacco from the pouch of his displeased but stoic neighbour …

And that is how I became an itinerant dealer for Gustav Beekhof’s paintings. My wanderings took me to the most remotest of European towns, and to the most hideous suburbs of those towns. Instead of dealing with rich bourgeois families, small museum curators or private collectors, Gustav’s mailed instructions directed me to shifty-eyed men, well-dressed and well-spoken indeed, but shifty in our negotiations. Besides, we effected our transactions in the oddest of places: warehouses, depots, repositories, seedy hotel rooms. I would remove the paintings from long, plastic cylinders similar to those that the Chinese use to carry their scrolls, unroll the merchandise they were expecting, and after a thorough inspection, the head of these delegations would produce a wad of bills, and without counting them push them into the pocket of my vest. They would leave me standing there without a word, although now and then, one of them was given orders to drive me to the centre of the town and drop me off at my hotel.

Gustav had advised me to deduct my fifteen percent from the purchases, deposit the maximum amount of cash that was permitted in one of the subsidiaries of a Dutch bank, found in Greece, Norway, Belgium, France, England, Luxembourg and Germany. If a large amount of cash remained, I was to travel to another country, locate another subsidiary and deposit the rest. Gustav had absolute faith in my integrity; at any time, I could have run off with thousands of francs, liras, pounds or any currency and simply disappeared. Of course the thought never occurred to me. As to the paintings themselves, they were sent through a special mail service along with a note at one of my hotels directing to the addresses where I had my the appointments. In this way I had no need to return to Amsterdam.

These proceedings continued without respite for two years as I scurried from country to country and town to town. I must admit that over the course of time I began to question the probity of the individuals I was dealing with, for all these transactions seemed enshrouded in mystery, carried out by dubious characters, each and every one of whom bore a rank odour of unprincipled morals, although their behaviour towards me was always impeccably polite, aloof indeed, but nevertheless perfectly respectful. I, thus, disregarded these apprehensions; after all, I was earning vast amounts of money. And I wasn’t one to, as the French say, cracher dans la soupe[6] !

One fine Spring day, I received six paintings at my hotel in Thessaloniki, Greece, and a note directing me to Istanbul, where an Armenian merchant was waiting impatiently to buy the paintings at a very handsome price. However, the note warned me that the merchant was a bit of a rogue, and a clever one at that. I smiled inwardly; I had been to Istanbul several times and could negotiate quite well in Turkish. I rubbed my hands ready for the joust …

It was on the fourth day of my arrival in Istanbul by bus from Thessaloniki that our appointment had been fixed in the Armenian’s small shop near the Armenian Church of Üç Horan (Trinity) inside the Fish Market. His shop, crowded with every object that one could possibly find on the face of the earth: wooden religious statues, candelabras, thuribles, musical instruments, Ottoman-styled hanging lamps, church paintings, ikons, antique furniture, travelling chests dating from the Ottoman Empire, sabres and shields, made it difficult for me to find the merchant seated behind a long, knotty mahogany table upon which had been stacked books, paper-weights and a scruffle of yellowing documents. He had a sinister look about him, doleful, suspicious, a darkly look that matched his dark frizzy hair, thick eyebrows and beard. When he noted my arrival he sat there in frozen silence which lasted longer than I had expected of a potential buyer of Gustav’s long-sought paintings. I sensed something amiss … something which did not sit well in this Ali Baba’s cave.

The Armenian stood and cleared away the books that encumbered his table. He bade me deposit the paintings in his outstretched arms. I took them out of the cylinder and placed them gently in the crooks of his arms, where like a mother holding her child, he cradled them for a few long seconds before laying them delicately on the knotty mahogany table.

Without a word he unrolled each one, admiring the colours, the textures, the shapes, the lines.

“Very nice … lovely !” he finally said in rough Turkish. “The colour saturation of this one is marvellous. And here, the crackle paste indeed gives the village a mediaeval aura. The application of mica flake certainly highlights the effects of the tempest over the sea, whilst here, the dry brush technique impresses an eerie velatura of the Scandinavian landscape.” He looked up at me. “And what do you think of Jasper Johns’ Between the Clock and the Bed ?” The question snapped me out of my reverie; no client had ever posed a question to me concerning the contents or quality of the paintings ; all my dealings had always been conducted with the utmost taciturnity.

“I don’t know … I’m not an art specialist, only a dealer.”

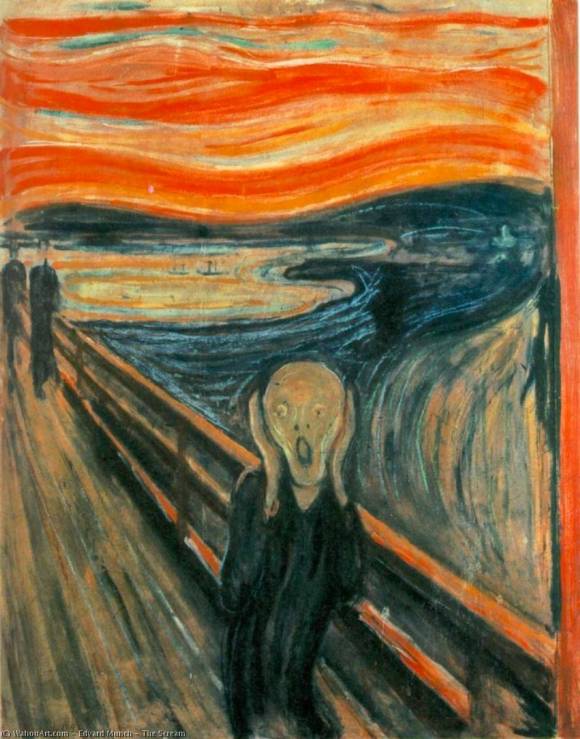

He chuckled : “Are you now ?” He touched the painting ever so delicately. “Pop art ? Expressionism ? What do you think, dealer ?” I remained silent, fidgeting about, the atmosphere had become unbearably oppressive. “Look, these fourteen colours set out like a lithograph should have been painted on Japan paper … do you follow me ?” I shook my head, ignorant of all these technical details. “Well, Mr Dealer, this is not Japan paper, consequently, the painting it not an original, which leads me to surmise that it’s a forgery !” The word forgery shot through me like a bullet. “So are those four, all falsified due to over-enthusiastic scrambling[7]. Only one is an original: The Scream, one of the eight versions by Munch, stolen this year from the Munchmusect in Oslo !” He stopped, stealing a glance at me. “How did you steal it?” he asked in a deep-toned voice, authoritative, one that does not brook rebuke. “And all the others stolen from museums, private collectors and galleries ? Just how do you do it ?” I cringed, feeling engulfed in a welter of confusion.

Mouth agape, I stammered : “I’m not a thief … I sell paintings for Gustav Beekhof, that’s all. I know nothing about where the paintings come from, except that …”

“I shall repeat the question once again,” retorted that deep-toned voice: “How do you steal them ?”

I stepped back. The whole affair was becoming a nightmare. “I told you I sell paintings for Gustav …”

My interrogator bent over the table and slapped me twice in the face. The violence sent me reeling backwards into some wooden statues. He circled round the table and stood menacingly over me. “We have been following your doings for months and months Mr Gustav Beekhof. Your repugnant affair has brought death and destruction to many innocent people.”

“Please, I don’t understand …”

“Shut up and listen !” And he punched me in the stomach, doubling me over. “Interpol shall be here in a moment or two to question you. But I would suggest you tell me everything here and now, for their methods are far from savoury.”

“Really … I’m not Gustav Beekhof … my name is Vigilius Notabene …”

“Oh really ?Vigilius Notabene ? Well now, Mr Notabene, let me inform you that you have been selling stolen paintings and forgeries to underworld criminal organisations and terrorist groups. Do you understand what that means Mr Notabene ? That means with the money they earn by selling what you have sold them for double or triple your amount, they buy arms to execute military personal and politicians, bombs to blow up train stations and aeroports. Did you think you could continue your lucrative affair with impunity ?” He grasped my collar, his face screwed up.

Suddenly, the shop door swung open. Three or four burly men dressed in civilian clothes wove their way towards us. They took me by the arms whilst the Armenian slapped me repeatedly across the face. I began to swoon. He turned to the men: “Gustav says his name is Vigilius Notabene.”

“But … I’m not Gustav !” I whimpered.

“Shall I juggle your memory ?” continued the Armenian. And that powerful fist drove into my chest. I cried out, hanging limp in the strong arms of the agents who looked on indifferently. “No, I’ll tell you your real name. Javier Fuentes, born and raised in Madrid, lover of bullfights and flamenco music. You left Spain for Holland where you changed your nationality and became Gustav Beekhof, amateur painter, counterfeiter and arch-cozen. Do you think we would never get on to your little affair ?” Again that hairy fist ploughed into my ribs.

I gasped for air. In low voices, the agents spoke to the Armenian in Dutch and in Turkish. I was amazed that I understood every word that was said. “Yes, yes Mr Beekhof, you understand everything we are saying. Polyglot, dilettante painter and musician, intrepid thief and casual traveller — it has taken us a while to corner you. And here we all are in my little shop. Cozy, eh ?”

A blow to the midriff sent me hurtling against a gaggle of porcelain geese, where I then slid squirming to the floor breaking the necks of two ! The agents violently grabbed my long, blond hair and stood me up.

“I’ll give you Gustav’s address …” I managed to gasp, my mouth filling with blood. Two agents squeezed my rounded shoulders so hard that I buckled over.

“Still on about Gustav, eh ? There is no Gustav Beekhof in Amsterdam on a barge. Gustav is right here in front of me, and there he will remain until he tells us the truth … If not …” I lifted my arms to ward off a blow, albeit none came.

“Come, come Gus, your mind has been unsettled by all these false identities ; all these wanderings in and out of cheap hotels, dealing with a bunch of thugs and killers. Fifteen percent ? Why give yourself fifteen percent when you deposit the rest in your own name in a Dutch bank account ? You must be completely daft!” I stared at my interrogator in disbelief. How did he know such precise details ?

“We know everything about you, Gussy!” as if reading my mind. “Everything except how you managed to steal these paintings from the museums. That remains a mystery to us all.”

“I’m Vigilius Notabene, born in Gotland on a farm. My parents died when I was thirteen so I left for Holland, Spain and France. In France …”

“Enough!” The Armenian began pummelling me. The agents stopped him. Then I heard the door of the shop swing open. I caught a glimpse of four men dressed in white ; tiny, white skull-caps coiffed their bald heads. They forced me into a straitjacket and hurried me into an ambulance. I was given an injection and that is all I remember until now …

I awoke in a small room, an all ghost-white room: white walls, door, window bars, curtains, bed and bedsheets, writing table. The whiteness pricked my eyes. My arms were strapped to my sides ; they had straitjacketed me. I lay helplessly surrounded by all this monochromatic melodrama.

One day a man, dressed in white whisked into the room, threw me a cursory glance, laid a notebook and pen very carefully on the white, metal table then strode to the bedside. He undid the straps of the straitjacket, pointed to the notebook on the table, and left as quickly as he came, wordlessly.

I stretched my stiff limbs and sat at the table. I had no idea where I was, and no one to turn to: no family, no friends, no lawyers … no one. I stared down at the white, lineless, notebook pages. Yes, I knew what they wanted from me. Ah, Gustav, you are a slippery sod. Here you are at last slipping out of that phantasmagoria of so many faces and places. So many existences that never existed! Take note that Vigilius Notabene will expose the truth of the past. As to Javier Fuentes, he had no future. Gustav is the true wayfarer, the ever-questing pilgrim present, here and now.

So in a renewed state of extreme excitement I now record on those very white pages :

“I met Gustav Beekhof whilst travelling in North Africa…”

.

[1] A small bar or tavern where people eat, drink and listen to flamenco music if there is a guitarist and a singer present.

[2] ‘Shambles, disorder, mess’.

[3] American painter ‘1930- ).

[4] Dutch painter (1635-1681)

[5] Norwegian painter (1880-1928)

[6] To spit in the soup’.

[7] A technique that allows to paint over areas of a painting to enhance the tone of dark-coloured areas.

Paul Mirabile is a retired professor of philology now living in France. He has published mostly academic works centred on philology, history, pedagogy and religion. He has also published stories of his travels throughout Asia, where he spent thirty years.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International