Editorial

‘How do you rebuild a life when all that remains is dust?’… Click here to read.

Translations

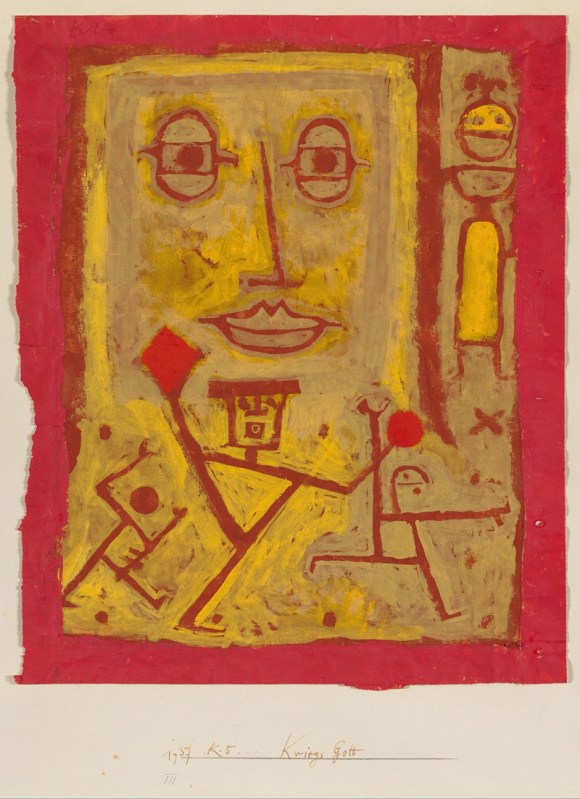

The Great War is Over and A Nobody by Jibanananda Das have been translated from Bengali by Professor Fakrul Alam. Click here to read.

Sukanta Bhattacharya’s poem, Therefore, has been translated from Bengali by Kiriti Sengupta. Click here to read.

Five poems by Soubhagyabanta Maharana have been translated from Odia by Snehaprava Das. Click here to read.

Animate Debris, a poem by Sangita Swechcha has been translated from Nepali by Saudamini Chalise. Click here to read.

Lost Poem, a poem by Ihlwha Choi has been translated from Korean by the poet himself. Click here to read.

Sonar Tori (Golden Boat), a poem by Tagore, has been translated from Bengali by Mitali Chakravarty. Click here to read.

Poetry

Click on the names to read the poems

Allan Lake, Shobha Tharoor Srinivasan, Ron Pickett, Ananya Sarkar, George Freek, Bibhuti Narayan Biswal, Jim Bellamy, Pramod Rastogi, Vern Fein, Saranyan BV, Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Juairia Hossain, Gautham Pradeep, Jenny Middleton, Mandavi Choudhary, Rhys Hughes

Musings/Slices from Life

Where Should We Go After the Last Frontiers?

Ahamad Rayees writes from a village in Kashmir which homed refugees and still faced bombing. Click here to read.

Vela Noble takes us for a stroll to the seaside at Adelaide. Click here to read.

Farouk Gulsara muses on hope. Click here to read.

Merdith Stephens writes from the Australian Outback with photographs from Alan Nobel. Click here to read.

Musings of a Copywriter

In Driving with Devraj, Devraj Singh Kalsi writes of his driving lessons. Click here to read.

Notes from Japan

In The Tent, Suzanne Kamata visits crimes and safety. Click here to read.

Essays

Public Intellectuals Walked, So Influencers Could Run

Lopamudra Nayak explores changing trends. Click here to read.

Where No One Wins or Loses a War…From Lucknow with Love

Prithvijeet Sinha takes us to a palace of a European begum in Lucknow. Click here to read.

Bhaskar’s Corner

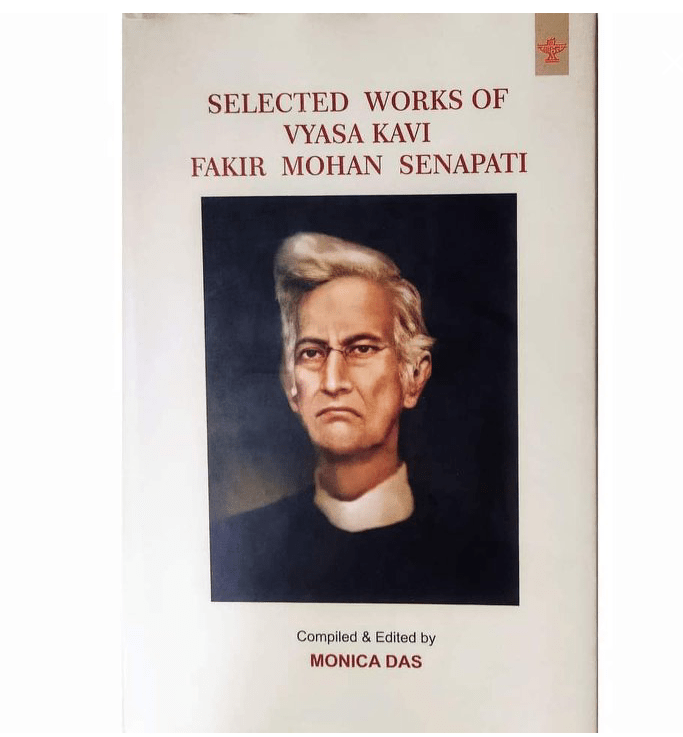

In Can Odia Literature Connect Traditional Narratives with Contemporary Ones, Bhaskar Parichha discusses the said issue. Click here to read.

Feature

The story of Hawakal Publishers, based on a face-to-face tête-à-tête, and an online conversation with founder Bitan Chakraborty with his responses in Bengali translated by Kiriti Sengupta. Click here to read.

Stories

The Year the Fireflies Didn’t Come Back

Leishilembi Terem gives a poignant story set in conflict-ridden Manipur. Click here to read.

Jeena R. Papaadi writes of the vagaries of human relationships. Click here to read.

Naramsetti Umamaheswararao relates a value based story in a small hamlet of southern India. Click here to read.

Book Excerpts

An excerpt from Wendy Doniger’s The Cave of Echoes: Stories about Gods, Animals and Other Strangers. Click here to read.

An excerpt from Mohua Chinappa’s Thorns in My Quilt: Letters from a Daughter to Her Father. Click here to read.

Book Reviews

Somdatta Mandal reviews Madhurima Vidyarthi’s Job Charnock and the Potter’s Boy. Click here to read.

Rakhi Dalal reviews Dhruba Hazarika’s The Shoot: Stories. Click here to read.

Satya Narayan Misra reviews Bakhtiyar K Dadabhoy’s Honest John – A Life of John Matthai. Click here to read.

Bhaskar Parichha reviews David C Engerman’s Apostles of Development: Six Economists and the World They Made. Click here to read.

.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International