By Niaz Zaman

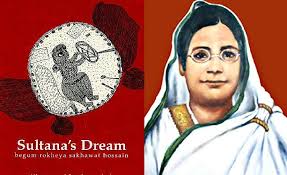

Recently, near Shamsun Nahar Hall, the second women’s hall of the University of Dhaka, a resident student defaced graffiti depicting Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein – popularly called Begum Rokeya. Black paint was used to smear her eyes and her mouth. Later, the student apologised for her action and promised to restore the image.

I do not know what upset the young woman. The picture is not offensive. The woman has her hair modestly covered. However, the manner of the defacing is troubling. The eyes have been painted over so that the woman cannot see; the mouth has been painted over so that the woman cannot speak. Why was the young woman denying the rights that Roquiah fought for, that the women of my generation demanded as their fundamental rights, and that the young women of today take for granted? Why was the young woman who defaced the picture denying the rights that the students against discrimination were claiming?

But, then to my surprise, I learned that this was not the only picture of Roquiah’s that had been defaced after August 5. In this other picture she had been given a beard and the derogatory word “magi[1]” written across it. What had Roquiah done to be dishonoured? What had made her controversial? Why was a young generation denying the changes that Roquiah had brought in young women’s lives by sheer perseverance and strength of will? On October 1, 1909, only four months after her husband’s death, Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein started a school in his name at Bhagalpur where she had been residing at the time. It was with great difficulty that she was able to persuade two families to send their daughters to her school. Of the five students, four were sisters.

Forced to leave Bhagalpur for personal reasons, she moved to Calcutta. However, she did not give up her dream and, two years later, on March 16, 1911, she re-started Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ School with eight students. At the time of her death on December 9, 1932, there were more than 100 girls studying at the school. Apart from teaching, the school encouraged girls to take part in sports and cultural activities. In recognition of her contribution to women’s education, the first women’s hall of the University of Dhaka was renamed “Ruqayyah Hall” in 1964.

More than a century has passed since Roquiah’s Sultana’s Dream was published in the Indian Ladies Magazine in 1905. In Bangladesh, in recent years, more than half of SSC graduates have been girls – who have also outperformed the boys. Though the female to male ratio goes down at the university level, women are working in different professions. Nevertheless, the danger to women that led to the institutionalisation of purdah and its extremes – which Roquiah questioned and decried for its often fatal results and which in Sultana’s Dream she reverses to put men in the “murdana” – still persists.

According to the UN, “Violence against women and girls remains one of the most prevalent and pervasive human rights violations in the world.” It is estimated that almost one in three women has been subjected to physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence, non-partner sexual violence, or both, at least once in her life. Numbers of women’s deaths in 2023 reveal that a woman was killed every 10 minutes.

Sadly, many of the killings are within the family, by husbands, brothers, fathers, mothers-in-law, and mothers – who have internalised the concept of honour and allow their daughters to be killed by those who should protect them. In early November, the murder of five-year-old Muntaha shocked the nation. We learned to our horror that her female tutor has been charged with the murder.

Neither education nor empowerment is proof against violence. What is the answer? Was Roqiuah wrong?

Had Roquiah been here today she would have been surprised to see so many young women wearing jeans but also hijabs – very different from the all-enveloping burqas of her times. Perhaps she would have been happy to see that the young women in the crowded streets were not afraid of the young men, and that, in August, when the traffic police were absent, they were confidently directing traffic. She would have been happy to see that the burqa had changed – as she had once suggested in an essay on the subject that it should.

However, she would have been shocked to see in recent months young men beating each other up with sticks – some even fatally. She had believed in education, believed that education was the answer to improving lives. She had striven to educate girls because she believed that it was education that would change their lives for the better. She would have been horrified to know that most of the young men beating each other up were students. She would perhaps have asked, Was I wrong? If education is not the answer, what is?

It is not enough then to educate women and to empower them. The tutor was educated and empowered. Perhaps what is important then is to realize as Roquiah did that one must have proper values. In “Educational Ideals for the Modern Indian Girl,” she stressed that India[2] must retain what is best about its traditions. Acquiring education did not mean that Indian women should discard their familial roles or forget their cultural values.

Though in this essay Roquiah emphasised traditional roles for women, she also believed that women had roles outside the family. Thus, in a letter to the Mussulman, dated December 6, 1921, she noted that four of the Muslim girls’ schools in Calcutta had headmistresses who had studied at Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ School.

Roquiah has been an icon for the generation of early feminists in East Pakistan/Bangladesh, many of whom like Shamsun Nahar Mahmud and Sufia Kamal were inspired by her and others like Nurunnahar Fyzenessa and Sultana Sarwat Ara who had studied at her school. She was one of the heroines for the generation of women activists of the mid-1970’s who made her call for emancipation their rallying cry. Women for Women, a research and study group, has a poster which quotes lines from Roquiah’s essay, “Subeh Sadek”: Buk thukiya bolo ma! Amra poshu noi. Bolo bhogini! Amra Asbab noi…Shokole shomobeshe bolo, amra manush. Proclaim confidently, daughter, we are not animals. Proclaim, sister, we are not inanimate objects… Proclaim it together, we are human beings.

Many people are frightened of the word feminism and believe it means a radicalism that would destroy society. But in reality, feminism is a call for equality and justice. Yes, Roquiah was a feminist, who saw the positive side of Islam and decried the absurdity and injustices of society. Roquiah would not have radically changed gender relationships but in both Sultana’s Dream and her novel Padmarag (1924), she suggests that women can have identities that are not dependent on their relationships to men. Yes, she was bound by her times, but the courage with which she lived her life – refusing to be shattered by personal tragedies and trying to make the world better for others – is still relevant today. As is the rationality that she stressed at all times.

[1] Insulting Bengali slang for woman

[2] India had not been partitioned to multiple entities when Roquiah lived.

Niaz Zaman is a retired academic, writer and translator.

(A version of this essay was published in the Daily Star, Bangladesh on December 9, 2024 under the title “How Significant Is Begum Rokeya Today?”)

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International