By Satyarth Pandita

It was the summer of 2019. The hostels were empty. Vacation had begun, and most students had already left for their hometowns. I was to leave the next day. While packing, I suddenly remembered The House of the Dead by Dostoevsky, which I had lent to a senior months ago.

I walked to his nearly abandoned hostel block and knocked on his half-open door. The room was dark—uncannily dark for the middle of the day. Thick curtains strangled the sunlight, casting the room into a premature night. There he lay on the bed, flat on his back, a laptop balanced on his belly. He handed me my book and resumed the video he had been watching—with monastic focus—from the fifty-sixth minute. It was footage of a man slowly cutting down a giant tree with an axe. He had been watching it, second by second, without skipping. He didn’t pause even when I left.

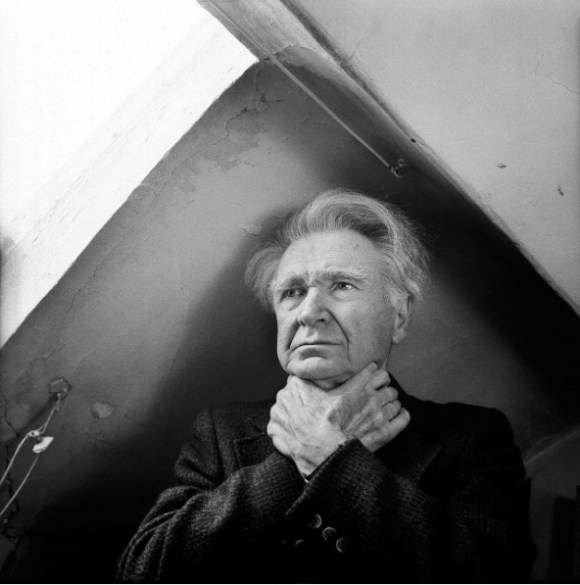

That was the man who introduced me to Emil Cioran.

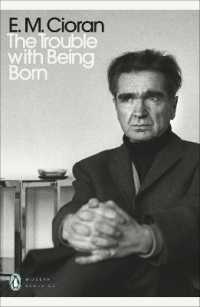

It was not until much later that I finally read him. The Trouble with Being Born opens at three o’clock in the morning with Cioran contemplating the futility of existence:

“Three in the morning. I realize this second, then this one, then the next: I draw up the balance sheet for each minute. And why all this? Because I was born. It is a special type of sleeplessness that produces the indictment of birth.”

The book proceeds as a collection of aphorisms circling around the nausea of existence and the idea of suicide as both temptation and reprieve.

Before I began to read his work, I tried to prepare myself by reading his biography and interviews. I wanted to understand the man behind the words, as if glimpsing his life might help me endure the weight of his thoughts. One such childhood story was telling. In an interview, Cioran confessed that when he was a child, one of his favourite pastimes was to play football with human skulls excavated by a gravedigger who was his friend. But little did he know at that time that what seemed like play was the seed of a lifelong fixation, depriving him of sleep, driving him to insomnia, in the hope of a long, never-ending slumber.

For Cioran, suicide was not a prescribed act but an ever-present possibility—a metaphysical escape hatch that bestowed dignity on existence. The mere awareness of this option granted him a strange form of freedom. The power of contemplating death, rather than executing it, was his way of wrestling with life’s meaninglessness. Suicide was philosophical, not prescriptive; a potential that loomed, yet never fully realised.

Yet one question persists: if Cioran saw life as an error and glorified suicide as the only coherent act, why did he never end his own life? His own words reveal the paradox:

“It is not worth the bother of killing yourself, since you always kill yourself too late.”

According to him, suicide comes too late to undo anything. The damage is already done. You’ve already suffered so much that ending it doesn’t fix anything—it merely ends an already exhausted life. By the time you do it, you’ve already endured the worst. You’ve already been broken, emptied, eroded by suffering. So, what’s the point? The act becomes redundant, even absurd.

At another moment, he offers a different angle, confessing his indecision:

“The energy and virulence of my taedium vitae continue to astound me. So much vigor in a disease so decrepit! To this paradox I owe my present incapacity to choose my final hour.”

Although Cioran ascribes his procrastination for suicide to his extreme weariness and boredom, yet, contrastingly, at another place, for him the power of ending one’s life is the greatest power.

“No autocrat wields a power comparable to that enjoyed by a poor devil planning to kill himself.”

This is the Cioranian condition: every insight undermined by its opposite, every aphorism shadowed by contradiction. He frames suicide as the ultimate sovereignty. The mere thought of being able to end one’s life surpasses the power of kings. And yet, he never exercised it. Instead, he transformed the possibility into philosophy, into aphorism, into art. His writing is not a system but an ongoing quarrel with himself. Instead of answering any particular question, his writings raise towers of new questions.

This tension, of circling but never arriving, defines his thought. He writes with precision, but his precision is not in building arguments―it is in dismantling them. Each aphorism is like a shard of glass: sharp, illuminating, but impossible to piece into a whole. Consider his reflection on sleeplessness:

“If there is so much discomfort and ambiguity in lucidity, it is because lucidity is the result of the poor use to which we have put our sleepless nights.”

Cioran knew the price of insomnia. To be awake at three in the morning is to be exiled from the world of the living, suspended in a state where thoughts spiral without conclusion. For him, insomnia was both torment and revelation. Perhaps, if Cioran had been able to sleep well, he might not have been trapped in this endless dialogue with futility. Instead, he lived in perpetual wakefulness, speaking to his own emptiness:

“No one has lived so close to his skeleton as I have lived to mine: from which results an endless dialogue and certain truths which I manage neither to accept nor to reject.”

“Once we appeal to our most intimate selves, once we begin to labor and to produce, we lay claim to gifts, we become unconscious of our own gaps. No one is in a position to admit that what comes out of his own depths might be worthless. ‘Self-knowledge’? A contradiction in terms.”

If, according to Cioran, true self-knowledge is not possible because we are too attached to our own depths and ego to judge ourselves truly, then there is no way he could have unearthed any truths about himself while living close to his emptiness (skeleton).

Cioran is, however, conscious of his contradictions. They were not accidents; they were his method. But are those contradictions a mirror of the thinkers he admired? In one of his aphorisms, he confesses:

“In the Orient, the oddest, the most idiosyncratic Western thinkers would never have been taken seriously, on account of their contradictions. This is precisely why we are interested in them. We prefer not a mind but the reversals, the biography of a mind, the incompatibilities and aberrations to be found there, in short those thinkers who, unable to conform to the rest of humanity and still less to themselves, cheat as much by whim as by fatality. Their distinctive sign? A touch of fakery in the tragic, a hint of dalliance even in the irremediable.”

Cioran points to that strange quality in writers like Nietzsche, Baudelaire or even himself-deeply tragic, but also stylistic, artful, and aware of the absurdities of their drama. For him, the appeal is not in the polished answers but in the drama of the doubt, in the visible struggle of a mind with itself.

Cioran is always in a perpetual state of perplexity. His thoughts are malleable. What is true for him today becomes obsolete tomorrow. And all this he has tried to betray through words. He knew his thoughts were mercurial, unstable. He confesses his extreme mental variability:

“I may change my opinion on the same subject, the same event, ten, twenty, thirty times in the course of a single day. And to think that each time, like the worst impostor, I dare utter the word “truth”!

Every time he pronounces a new opinion, he does so with the implicit suggestion that this one is right―that this is the truth. He accuses himself of a kind of fraud, i.e. knowing his judgments are volatile, yet he delivers them as if they were true.

Amidst all these contradictions and paradoxes, what, then, did Cioran truly long for? Because what he wishes for in one place, he rejects in the other. But there is one feeling, or a longing, that recurs throughout the book―a longing for a time before time, a time before creation. He speaks of it with yearning, as if for a paradise never lost yet never possessed.

“There was a time when time did not yet exist…. The rejection of birth is nothing but the nostalgia for this time before time.”

“O to have been born before man!”

This longing resonates the idea of what the Portuguese call saudade, a longing for something that never was or will never be attainable. Unlike nostalgia, which mourns a past that once existed, saudade is a longing for an unattainable ideal, a sense of melancholic absence that can only be evoked in poetry and art. This yearning captures the profound melancholy that saturates Cioran’s philosophy—a feeling that seeps like a grey mist into a distant blue sky. And yet he admits the impossibility of feeling it:

“It is impossible to feel that there was a time when we did not exist. Hence our attachment to the personage we were before being born.”

We cannot experience absence, so we cannot truly imagine our non-being before birth. In our memory and awareness, we’ve always been — we cannot step outside ourselves to picture a time when we were nothing. This is not a metaphysical claim, but a psychological one.

If Cioran were a simple nihilist, one who believed in nothing and cared for nothing, why would he write at all? Why invest thought and feeling into a world he found so painfully absurd? The answer lies in his profound sensitivity. Cioran was a nihilist who felt too much. He was wounded by life. Writing, for him, was both a compulsion and a failure. Cioran was a master of paradox. He despised life yet wrote nine books about it. He dismissed language as futile yet clung to words as his only tool. He longed for silence yet confessed:

“We write books because we are ashamed of not having been able to remain silent.”

Writing was a failure to keep still in the face of futility. Yet silence was a greater failure, an impossibility. Thus, he turned his torment into words. For him, each book was a kind of reprieve. Perhaps, his most telling aphorism is this:

“A book is postponed suicide.”

For him, writing a book symbolised a form of delayed self-destruction or self-sacrifice, where the author channels inner turmoil into the work and thus postpones an existential “death”.

On a similar note, he explains the need for language, the need for writing.

“The more injured you are by time, the more you seek to escape it. To write a faultless page, or only a sentence, raises you above becoming and its corruptions. You transcend death by the pursuit of the indestructible in speech, in the very symbol of nullity.”

Language itself, for Cioran, is paradoxical. It is both empty (words are mere signs, lacking substance) and the only tool we have to approach the eternal. So even while writing may seem futile or illusory, it’s also the only space where something indestructible can be momentarily glimpsed.

The Cioranian paradox yet again comes into the picture, where he proclaims:

“One must be mad or drunk,” the Abbe Sieyès said, to speak well in the known languages. One must be drunk or mad, I should add, to dare, still, to use words, anyword….”

In his earlier aphorisms, he advocates for the meaning or use of writing, but then in the following aphorisms, he expresses the futility of writing, or words, of language itself. To use language sincerely is itself madness. If words distort, then every attempt to write is a betrayal. And yet he could not stop writing. This was the paradox that sustained him.

In the book, Cioran traces this disposition back to his family:

“Every family has its own philosophy. One of my cousins, who died young, once wrote me: ‘It’s all the way it’s always been and probably always will be until there’s nothing left any more.’”

Whereas my mother ended the last note she ever sent me with this testamentary sentence: “Whatever people try to do, they’ll regret it sooner or later.

“Nor can I even boast of having acquired this vice of regret by my own setbacks. It precedes me, it participates in the patrimony of my tribe. What a legacy, such unfitness for illusion!”

Cioran interjects with irony: he can’t even take credit for being regret-prone as a result of his own failures. It’s not just personal experience that made him this way—regret runs deeper; it’s not biographical but ancestral.

Yet Cioran was not only drawn to grand despair. He had a peculiar love for the banal, the ordinary, and the infinitesimal things in our everyday life. Like Georges Perec’s concept of the “infraordinary”―the unnoticed texture of daily life―Cioran wrote:

“The intrinsic value of a book does not depend on the importance of its subject (else the theologians would prevail, and mightily), but on the manner of approaching the accidental and the insignificant, of mastering the infinitesimal. The essential has never required the least talent.”

“No true art without a strong dose of banality. The constant employment of the unaccustomed readily wearies us, nothing being more unendurable than the uniformity of the exceptional.”

For him, the ordinary was not a distraction from philosophy but its truest field.Emil Cioran was also deeply influenced by the Eastern philosophies of Hinduism and Buddhism. He often returned to the idea of renunciation and detachment:

“It is trifling to believe in what you do or in what others do. You should avoid simulacra and even ‘realities’; you should take up a position external to everything and everyone, drive off or grind down your appetites, live, according to a Hindu adage, with as few desires as a ‘solitary elephant’.”

“I am enraptured by Hindu philosophy, whose essential endeavor is to surmount the self; and everything I do, everything I think is only myself and the self’s humiliations.”

And yet, while he admired Buddha’s teachings on suffering, he could not detach himself from his own disappointments:

“My faculty for disappointment surpasses understanding. It is what lets me comprehend Buddha, but also what keeps me from following him.”

Cioran is the kind of person who is aware of his suffering, knows the cure, but won’t take the medicine because the illness has become who he is. For him, disappointment is instinctive, all-consuming and more intimate than thought itself. Since Buddha taught that life is marked with Dukha (suffering/disappointment), Cioran feels connected to Buddhist philosophy, but he cannot follow that path because to follow Buddha requires detachment, letting go of even disappointment, which Cioran cannot do.

Cioran also reflects on a peculiar way to cope with life’s anxieties. He says:

“In order to conquer panic or some tenacious anxiety, there is nothing like imagining your own burial. An effective method, readily available to all…”

This aphorism resonates directly with the Hindu practices, as especially embodied in Banaras (Varanasi), where the city itself is a living memento mori, where cremation fires at Manikarnika Ghat never extinguish, and death is not hidden away but displayed as part of life. In Varanasi, the pilgrims are encouraged to watch the burning pyres, not to indulge morbidity but to confront impermanence directly. But even here, he reminds us of the futility of origins:

“The emphasis on birth is no more than the craving for the insoluble carried to the point of insanity.”

He knows that obsessing over the question of birth, of life, is futile, insoluble and unanswerable. To take this obsession with origins, with life’s beginning, so seriously — to revere it, to found ideologies or hope on it — is, for Cioran, madness. It means you are so committed to wrestling with the unanswerable that you’ve abandoned sanity. It’s a form of spiritual masochism: continually turning to the one question — Why was I born? — that has no satisfying answer.

A man who spent all his life thinking about the tragedy of birth, the futility of life and the meaning of death confesses at one point in the book that he has known nothing new in all his later years that he knew when he was young. All his thinking, the sleepless nights, the anxiety and the dread have contributed nothing to further his knowledge. In his own words:

“What I know at sixty, I knew as well at twenty. Forty years of a long, superfluous, labour of verification.”

Despite all of Cioran’s nihilistic or dark thoughts, he granted failure a strange dignity:

“This is how we recognize the man who has tendencies toward an inner quest: he will set failure above any success, he will even seek it out, unconsciously of course. This is because failure, always essential, reveals us to ourselves, permits us to see ourselves as God sees us, whereas success distances us from what is most inward in ourselves and indeed in everything.”

“Failure, even repeated, always seems fresh; whereas success, multiplied, loses all interest, all attraction.”

In this sense, he inverts conventional wisdom: failure is not defeat but a revelation, a mirror of the self, stripped of illusion.

The Trouble with Being Born is not an easy read. The book is a constant rumination and meditation on the bliss of nonexistence, the deep nostalgia for a state before being, before consciousness, before identity. There is an uneasiness, an anxiety, a restlessness and an unknown dread that creeps in and grows with every sentence one reads. It has the potential to scratch the old wounds of one’s soul, which one has forgotten. Yet, if one reads and analyses the aphorisms from a distance with a particular perspective, it can also provoke laughter―the laughter of someone who has stared too long at the abyss and found it absurd.

Emil Cioran is like a chess master, and each of his aphorisms is a calculated move. For every aphorism that he mentions, he has already anticipated the reader’s move. He has anticipated every question, especially the most obvious one, why he did not kill himself and his reply is already there.

Reading Cioran is like walking into a fog. Every sentence brings a chill of recognition, but also a deeper uncertainty. He lived next to his emptiness, befriended it, argued with it, laughed at it—and wrote it down. He is frustrating. He contradicts himself. He writes aphorisms that sound like suicide notes, only to retract them with a smirk. But that is the trouble with Cioran. He lived. He wrote. He suffered. And somehow, he made it all sound beautiful.

And perhaps that’s the final paradox: the man most disillusioned with life gave us one of its most enduring voices.

After reading him, I’ve come to admire Cioran because, to me, he is like a mathematician devoted to solving the equation of life and death. Every variable, every permutation and combination, has passed through his mind; the possibilities now stand exposed on the blackboard, supporting and undermining one another in turn. The solution, if it exists, hovers just within sight—yet he chooses to work through it endlessly, not in pursuit of an answer, but in devotion to the act itself. He is a modern Sisyphus, who has not merely accepted his fate, but learned to love the rolling of the boulder, again and again, to the mountain’s top.

Satyarth Pandita is a PhD student at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru. He completed his dual degree, a Bachelor of Science and Master of Science in Biological Sciences (major) and Humanities and Social Sciences (minor), at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Bhopal (IISERB). His works have appeared in various newspapers and periodicals, including The Quint, Outlook India, The Wire, Madras Courier, Borderless, and Kitaab, among others.

Links to Satyarth’s published works, email address and social media handles can be found here.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International