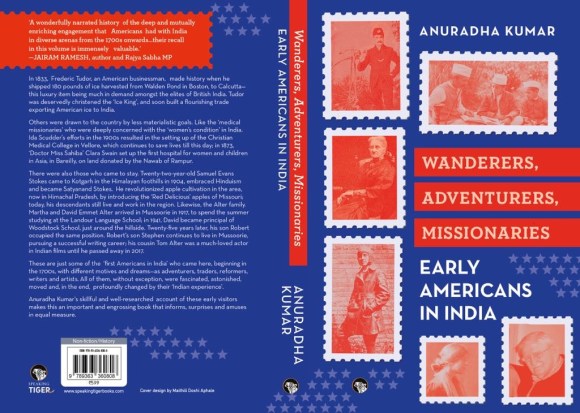

A review of Anuradha Kumar’s Wanderers, Adventurers, Missionaries: Early Americans in India (Speaking Tiger Books) and an interview with the author

Migrants and wanderers — what could be the differences between them? Perhaps, we can try to comprehend the nuances. Seemingly, wanderers flit from place to place — sometimes, assimilating bits of each of these cultures into their blood — often returning to their own point of origin. Migrants move countries and set up home in the country they opt to call home as did the family the famous Indian actor, Tom Alter (1950-2017).

Anuradha Kumar’s Wanderers, Adventurers, Missionaries: Early Americans in India captures the lives and adventures of thirty such individuals or families — including the Alter family — that opted to explore the country from which the author herself wandered into Singapore and US. Born in India, Kumar now lives in New Jersey and writes. Awarded twice by the Commonwealth Foundation for her writing, she has eight novels to her credit. Why would she do a whole range of essays on wanderers and migrants from US to India? Is this book her attempt to build bridges between diverse cultures and seemingly diverse histories?

As Kumar contends in her succinct introduction, America and India in the 1700s were similar adventures for colonisers. In the Empire Podcast, William Dalrymple and Anita Anand do point out that the British East India company was impacted in the stance it had to colonisers in the Sub-continent after their experience of the American Revolution. And America and India were both British colonies. They also were favourites of colonisers from other European cultures. Just as India was the melting pot of diverse communities from many parts of the world — even mentioned by Marco Polo (1254-1324) in The Kingdom of India — America in the post-Christopher Columbus era (1451-1546) provided a similar experience for those who looked for a future different from what they had inherited. The first one Kumar listed is Nathaniel Higginson (1652-1708), a second-generation migrant from United Kingdom, who wandered in around the same time as British administrator Job Charnock (1630-1693) who dreamt Calcutta after landing near Sutanuti[1].

Kumar has bunched a number of biographies together in each chapter, highlighting the commonality of dates and ventures. The earliest ones, including Higginson, fall under ‘Fortune Seekers From New England’. The most interesting of these is Fedrick Tudor (1783-1864), the ice trader. Kumar writes: “In Calcutta, Dwarkanath Tagore, merchant and patron of the arts (Rabindranath Tagore’s grandfather), expressed an interest to involve himself in ice shipping, but Tudor’s monopoly stayed for some decades more. Tagore was part of the committee in Calcutta along with Kurbulai Mohammad, scion of a well-established landed family in Bengal, to regulate ice supply.”

Also associated with the Tagore family, was later immigrant Gertrude Emerson Sen (1890-1982, married to Boshi Sen). She tells us, “Tagore wrote Foreword to Gertrude Emerson’s Voiceless India, set in a remote Indian village and published in 1930. Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore called Emerson’s efforts, ‘authentic’.” She has moved on to quote Tagore: “The author did not choose the comfortable method of picking up information from behind lavish bureaucratic hospitality, under a revolving electric fan, and in an atmosphere of ready-made social opinions…She boldly took in on herself unaided to enter a region of our life, all but unexplored by Western tourists, which had one great advantage, in spite of its difficulties, that it offered no other path to the writer, but that of sharing the life of the people.’” Kumar writes of an Afro-American scholar, called Merze Tate who came about 1950-51 and was also fascinated by Santiniketan as were some others.

Another name that stuck out was Sam Higginbottom, who she described as “the Farmer Missionary” for he was exactly that and started an agricultural university in Allahabad. Around the same time as Tagore started Sriniketan (1922), Higginbottom was working on agricultural reforms in a different part of India. In fact, Uma Dasgupta mentions in A History of Sriniketan: Rabindranath Tagore’s Pioneering work in Rural Reconstruction that Lord Elimhurst, who helped set up the project, informed Tagore that “another Englishman” was doing work along similar lines. Though as Kumar has pointed out, Higginbottom was a British immigrant to US — an early American — and returned to Florida in 1944.

There is always the grey area where it’s difficult to tie down immigrants or wanderers to geographies. One such interesting case Kumar dwells on would be that of Nilla Cram Cook, who embraced Hinduism, becoming in-the process, ‘Nilla Nagini Devi’, as soon as she reached Kashmir with her young son, Sirius. She shuttled between Greece, America and India and embraced the arts, lived in Gandhi’s Wardha ashram and corresponding with him, went on protests and lived like a local. Her life mapped in India almost a hundred years ago, reads like that of a free spirit. At a point she was deported living in an abject state and without slippers. Kumar tells us: “Her work according to Sandra Mackey combined ‘remarkable cross-cultural experimentation’ and ‘dazzling entrepreneurship.’”

The author has written of artists, writers, salesmen, traders (there’s a founder/buyer of Tiffany’s), actors, Theosophists, linguists fascinated with Sanskrit, cyclists — one loved the Grand Trunk Road, yet another couple hated it — even a photographer and an indentured Afro-American labourer. Some are missionaries. Under ‘The Medical Missionaries: The Women’s Condition’, she has written of the founders of Vellore Hospital and the first Asian hospital for women and children. Some of them lived through the Revolt of 1857; some through India’s Independence Movement and with varied responses to the historical events they met with.

Kumar has dedicated the book to, “…all the wanderers in my family who left in search of new homes and forgot to write their stories…” Is this an attempt to record the lives of people as yet unrecorded or less recorded? For missing from her essays are famous names like Louis Fischer, Webb Miller — who were better known journalists associated with Gandhi and spent time with him. But there are names like Satyanand Stokes and Earl and Achsah Brewster, who also met Gandhi. Let’s ask the author to tell us more about her book.

What made you think of doing this book? How much time did you devote to it?

These initially began as essays for Scroll; short pieces about 1500-1600 words long. And the beginnings were very organic. I wrote about Edwin Lord Weeks sometime in 2015. But the later pieces, most of them, were part of a series.

I guess I am intrigued by people who cross borders, make new lives for themselves in different lands, and my editors—at Scroll and Speaking Tiger Books—were really very encouraging.

After I’d finished a series of pieces on early South Asians in America, I wanted to look at those who had made the journey in reverse, i.e., early Americans in India, and so the series came about, formally, from December 2021 onward. I began with Thomas Stevens, the adventuring cyclist and moved onto Gertrude Emerson Sen, and then the others. So, for about two years I read and looked up accounts, old newspapers, writings, everything I possibly could; I guess that must mean a considerable amount of research work. Which is always the best thing about a project like this, if I might put it that way.

What kind of research work? Did you read all the books these wanderers had written?

Yes, in effect I did. The books are really old, by which I mean, for example, Bartolomew Burges’ account of his travels in ‘Indostan’ written in the 1780s have been digitized and relatively easy to access. I found several books on Internet Archive, or via the interlibrary loan system that connects libraries in the US (public and university). I looked up old newspapers, old magazine articles – loc.gov, archive.org, newspapers.com, newspaperarchive.com, hathitrust.org and various other sites that preserve such old writings.

You do have a fiction on Mark Twain in India. But in this book, you do not have very well-known names like that of Twain. Why?

Not Twain, but I guess some of the others were well-known, many in their own lifetime. Satyanand Stokes’ name is an easily recognisable still especially in India, and equally familiar is Ida Scudder of the Vellore Medical College, and maybe a few others like Gertrude Sen, and Clara Swain too. I made a deliberate choice of selecting those who had spent a reasonable amount of time in India, at least a year (as in the case of Francis Marion Crawford, the writer, or a few months like the actor, Daniel Bandmann), and not those who were just visiting like Mark Twain or passing through. This made the whole endeavour very interesting. When one has spent some years in a foreign land, like our early Americans in India, one arguably comes to have a different, totally unique perspective. These early Americans who stayed on for a bit were more ‘accommodating’ and more perceptive about a few things, rather than supercilious and cursory.

And it helped that they left behind some written record. John Parker Boyd, the soldier who served the Nizam as well as Holkar in Indore in the early 1800s, left behind a couple of letters of complaint (when he didn’t get his promised reward from the East India Company) and even this sufficed to try and build a complete life.

How do these people thematically link up with each other? Do their lives run into each other at any point?

Yes, I placed them in categories thanks to an invaluable suggestion by Dr Ramachandra Guha, the historian. I’d emailed him and this advice helped give some shape to the book, else there would have been just chapters following each other. And their lives did overlap; several of them, especially from the 1860s onward, did work in the same field, though apart from the medical missionaries, I don’t think they ever met each other – distances were far harder to traverse then, I guess.

What is the purpose of your book? Would it have been a response to some book or event?

I was, and am, interested in people who leave the comforts of home to seek a new life elsewhere, even if only for some years. Travelling, some decades ago, was fraught with risk and uncertainty. I admire all those who did it, whether it was for the love of adventure, or a sense of mission. I wanted to get into their shoes and see how they felt and saw the world then.

Is this because you are a migrant yourself? How do you explain the dedication in your book?

I thought of my father, and his cousins, all of whom grew up in what was once undivided Bengal. Then it became East Pakistan one day and then Bangladesh. Suddenly, borders became lines they could never cross, and they found new borders everywhere, new divisions, and new homes to settle down in. They were forced to learn anew, to always look ahead, and understand the world differently.

When I read these accounts by early travellers, I sort of understood the sense of dislocation, desperation, and sheer determination my father, his cousins felt; maybe all those who leave their homes behind, unsure and uncertain, feel the same way.

You have done a number of non-fiction for children. And also, historical fiction as Aditi Kay. This is a non-fiction for adults or all age groups? Do you feel there is a difference between writing for kids and adults?

I’d think this is a book for someone who has a sense of history, of historical movements, and change, and time periods. A reader with this understanding will, I hope, appreciate this book.

About the latter half of your question, yes of course there is a difference. But a good reader enters the world the writer is creating, freely and fearlessly, and I am not sure if age decides that.

You have written both fiction and non-fiction. Which genre is more to your taste? Elaborate.

I love anything to do with history. Anything that involves research, digging into things, finding out about lives unfairly and unnecessarily forgotten. The past still speaks to us in many ways, and I like finding out these lost voices.

What is your next project? Do you have an upcoming book? Do give us a bit of a brief curtain raiser.

The second in the Maya Barton-Henry Baker series. In this one, Maya has more of a lead role than Henry. It’s set in Bombay in the winter of 1897, and the plague is making things scary and dangerous. In this time bicycles begin mysteriously vanishing… and this is only half the mystery!

We’ll look forward to reading a revival of the characters fromThe Kidnapping of Mark Twain: A Bombay Mystery. Thanks for your time and your wonderful books.

.

[1] Now part of Kolkata (Calcutta post 2001 ruling)

Click here to read an excerpt from Wanderers, Adventurers, Missionaries: Early Americans in India

(This review and online interview is by Mitali Chakravarty)

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International