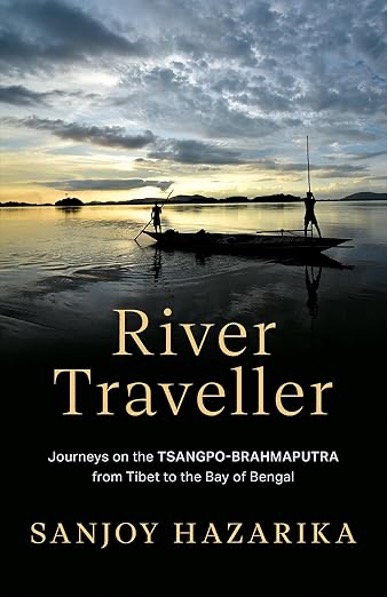

Book Review by Somdatta Mandal

Title: River Traveller: Journeys on the TSANPO-BRAHMAPUTRA from Tibet to the Bay of Bengal

Author: Sanjoy Hazarika

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

Sanjoy Hazarika, a former reporter for the New York Times, dons many hats, combining roles as researcher, columnist, mentor and practitioner. Over decades this veteran journalist has travelled extensively across the Northeast and its neighbourhood. His interests include developments in Myanmar, Bhutan, Tibet (PRC), Bangladesh and Nepal and he has produced over a dozen documentaries including on the Brahmaputra, dolphins, governance, conflict, and rights.

River Traveller tells the story of a great river, as powerful as it is mysterious. The Brahmaputra rises in Tibet, travels through three countries and, after travelling over 2,900 kms, flows into the Bay of Bengal. But the most interesting part is that this river is known by many names: Yarlung Tsangpo and Po Tsangpo in Tibet, Siang in Arunachal Pradesh, Brahmaputra in Assam, the Jamuna in Bangladesh, merging with the Ganga at Arichar Ghat, to form the vast Padma on its unending flow to the Bay of Bengal and its quest for union with the sea.

This book has come together over decades of travels on this braided river (including on the boat clinics that he launched in 2005 in Assam) where Hazarika had seen its beauty and faced its wrath, been stuck on sandbanks and swept out to sea. He listened to those who plied the boats, the pilots, drivers, fishermen and their families, the sick and the ailing, women and children, Buddhist and Hindu monks, Sikh and Muslim priests, officials, politicians, students and scientists. He has listened to poets, singers, writers and artists, and to businessfolk and daily wage earners, boat builders, contractors, tea planters and workers. The writer amalgamated all their stories which were a mix of sadness, a determination to survive, an acceptance of fate and joy. Therefore, his traveller’s tales span not just his own journeys but the stories of those who had gone before him. Like the river, the region and its neighbourhood “never cease to delight, surprise, inspire, sadden and confound.”

Of course, the most ostentatious reason for Hazarika’s travels is the filming of documentaries on the river at different points of time. His first travel was for the film A River’s Story, the Quest for the Brahmaputra that he scripted and produced with Jahnu Barua as the director, Sudheer Palsane as cinematographer, Sanjoy Roy and Jugal Debta as audiographers as well as many others. The thrust area was to study the stories of the river and its people, from its beginnings in the Tibetan Plateau to the end in the Bay of Bengal. It wasn’t about science and theory, or politics and the environment, or climate change, but about the river and its moods, and especially its people and their relationship with each other, through history and changing geography, culture, faith, peace and poverty.

In the second venture, Gautam Bora was director and cinematographer of Brahmaputra, a six-part series for Doordarshan, shot in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam. In his third venture, he was involved in the making of Children of the River, the Xihus of Assam, which was directed and filmed by Maulee Senapati and where he learned much about dolphins.

Divided into three parts, the book is as exhaustive a study on the river as can be imagined. The Brahmaputra is one of the world’s longest and widest rivers—sustaining entire civilizations and agrarian systems. It has fascinated cartographers, lured adventurers, attracted kings and dynasts, and has supported life and ways of living by its banks. Before beginning with the actual travel in Part One that includes his sojourns in Tibet and Arunachal Pradesh, Hazarika goes back to history of the thirteenth century when in about 1215 AD, the Tai-Ahom prince Siu-ka-pha left his native land now on the China-Myanmar border and undertook a long march before settling down in Charaideo, his capital, with its surrounding flat plains, rich red soil, streams and the vast Brahmaputra nearby. After that for centuries, traders, smugglers, fighters, fugitives, goods, cuisines, languages and ideas as well as religions and religious people have travelled in either direction on the Siu-ka-pha trail.

Hazarika begins his yatra in Tibet and narrates how the challenges relating to it were not new. He describes a Tibet that was trying to hold on to its cultural legacy in the face of Chinese rule and the land’s exploitation for its resources. He recounts stories of explorers, spymasters and mapmakers, especially a motley crowd of intrepid men in the service of the East India Company and the Survey of India, who discovered the route of the river especially when it’s source was hidden in the most inhospitable terrain on earth. They finally solved the puzzle of the vanishing river and established that the Brahmaputra and the Tsangpo were the same river.

In Arunachal Pradesh, Hazarika views the river from a helicopter and to him it resembled a great, brown meandering serpent, moving in huge loops, with many channels; at times, a stream or two which joined the flow backed down on themselves, creating elegant oxbow lakes. At Gelling, the first village on the Indian side, the turbulent Tsangpo churns its way through a narrow valley after a cascading drop from Tibet. Here for the first time the Tsangpo changes its name and is known as the Siang or Dibang for the next 200 kilometers before it enters Assam. At a place called Kobo, the Lohit meets the Dibang, Noa Dihing, Tengapani and Siang and develops the immense power that is mirrored in the Brahmaputra in full flow.

Part Two comprising of nine chapters focuses on Assam. After the earthquake of 1950, water ‘blockades’ happened not just on the Siang but also on several other rivers flowing into the Assam Valley and as a result the river changed its course, lifted the riverbed, flattened the banks and land, and braided it in many places far more than ever before. As a result, many towns like Rohmoria, Sadiya simply vanished after being embraced by flood waters, and places like Barpeta, Goalpara and Dhubri underwent demographic changes.

In separate chapters we learn about the tea gardens of Assam, the influence of Srimanta Sankaradeva and his satras[1], about the great river island Majuli, the singer Bhupen Hazarika, the presence of dolphins in the Brahmaputra, the thousands of islands known as the chars and saporis, which are permanent in their impermanence, where the Muslim residents are known as Miyas, the large number of migrants that inhabit the place, the sand bars and sandbanks that dot the riverscape from Upper Assam and how the collection of sand and its sale and distribution has changed the lives of many along the river to the point where it enters Bangladesh. He also gives us details about the ferry system, the boat clinics on the river that represent both a dream and a reality, as annually, nearly three lakh people are treated in these mobile structures.

The third part of the narrative obviously ends with four chapters on Bangladesh. We are told how to move from a slow riverine economy to a bustling one is quite challenging. This section includes fear of being hunted by pirates on an open sea, the faith in the navigators, ‘drivers’, pilots and other crew members who can read the mind of the river, the trip to the confluence of the Ganga and the Brahmaputra along with a Bangladeshi singer called Maqsoodul Haque or Mac. Both these rivers have different names in Bangladesh. The Ganga is the Padma while the Brahmaputra is the Jamuna. We are told about the story of the island known to Indians as New Moore Island and to the Bangladeshis as Sandwip island that appeared and disappeared, causing a diplomatic furore. The Brahmaputra’s role in shaping the destiny of low-lying Bangladesh is well-established and we are told of the connectedness of the people to the river, on either side of the human-made border. There are many places where the turbulent river refuses to accept human markers and controls and the border just remains an imaginary line snaking across shifting sands.

After reading about the multifarious experiences of Hazarika, it is needless to state that this book of non-fiction mesmerizes the readers to such a great extent that one hankers for more information. It is best to conclude the review by quoting from the poetic way Hazarika himself speaks at the end of the book about the interconnectedness that lies even in a grain of sand:

“I have traversed the river, shared my secrets with it and laid my fears and troubles to rest there. It too has spoken to me and has been kind and generous, in the midst of its vastness and power, to someone who could not swim.

“River Traveller is deeply personal and piloted by my life and learnings on the river, failings, shortcomings, understanding. It’s about shared stories, loves gained and lost, inspiration and sadness. Autobiographical in parts, it navigates history and crosses borders.

“Many travels beckon, for the river still calls.“

From extremism to environmental responsibility, politics to ethnography, River Traveller touches on a multitude of subjects, and is an enduring study of human life and natural history. It is a rich and memorable portrait of one of the mightiest rivers on our planet. The colour photographs that are included in the middle of the narrative add extra charm to the narration. A volume worth possessing and reading and rereading repeatedly.

[1] Specialised Vaishnavi monasteries in Assam serving as socio-religious, cultural and educational centres since the fifteenth century.

.

Somdatta Mandal, critic and translator, is a former Professor of English at Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, India.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International