If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?

'Ode to the West Wind', Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 -1822)

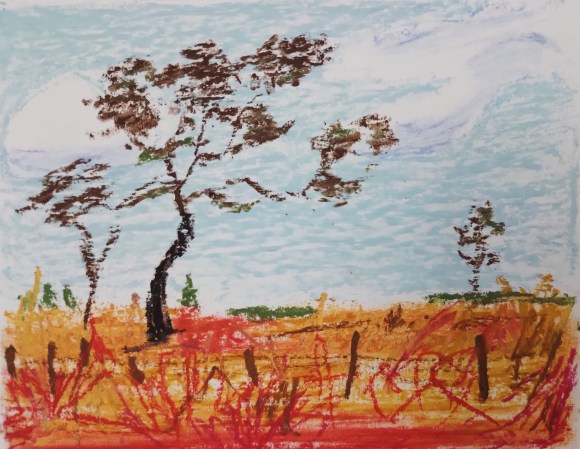

The idea of spring heralds hope even when it’s deep winter. The colours of spring bring variety along with an assurance of contentment and peace. While wars and climate disasters rage around the world, peace can be found in places like the cloistered walls of Sistine Chapel where conflicts exist only in art. Sometimes, we get a glimpse of peace within ourselves as we gaze at the snowy splendour of Himalayas and sometimes, in smaller things… like a vernal flower or the smile of a young child. Inner peace can at times lead to great art forms as can conflicts where people react with the power of words or visual art. But perhaps, what is most important is the moment of quietness that helps us get in touch with that inner voice giving out words that can change lives. Can written words inspire change?

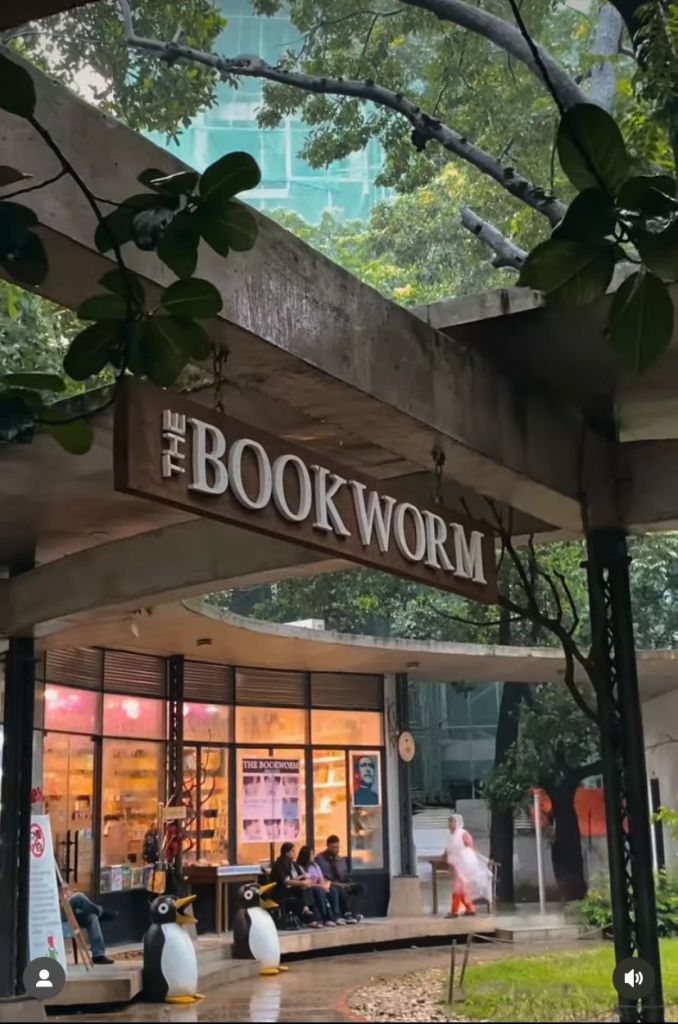

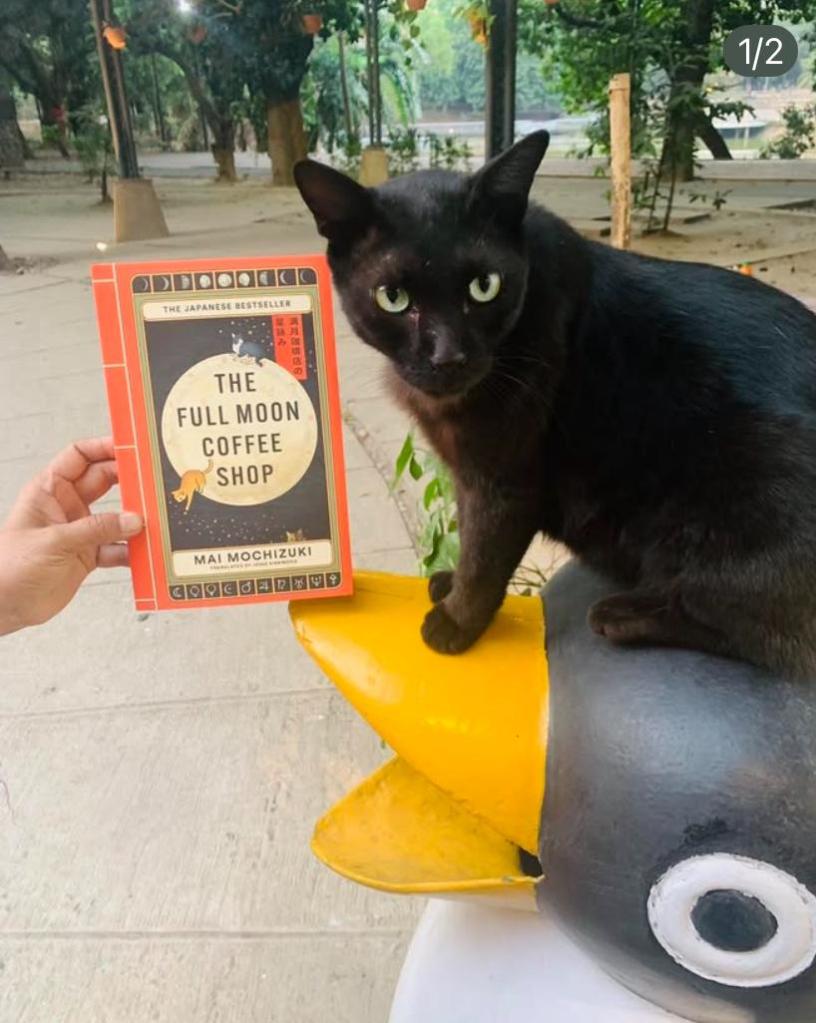

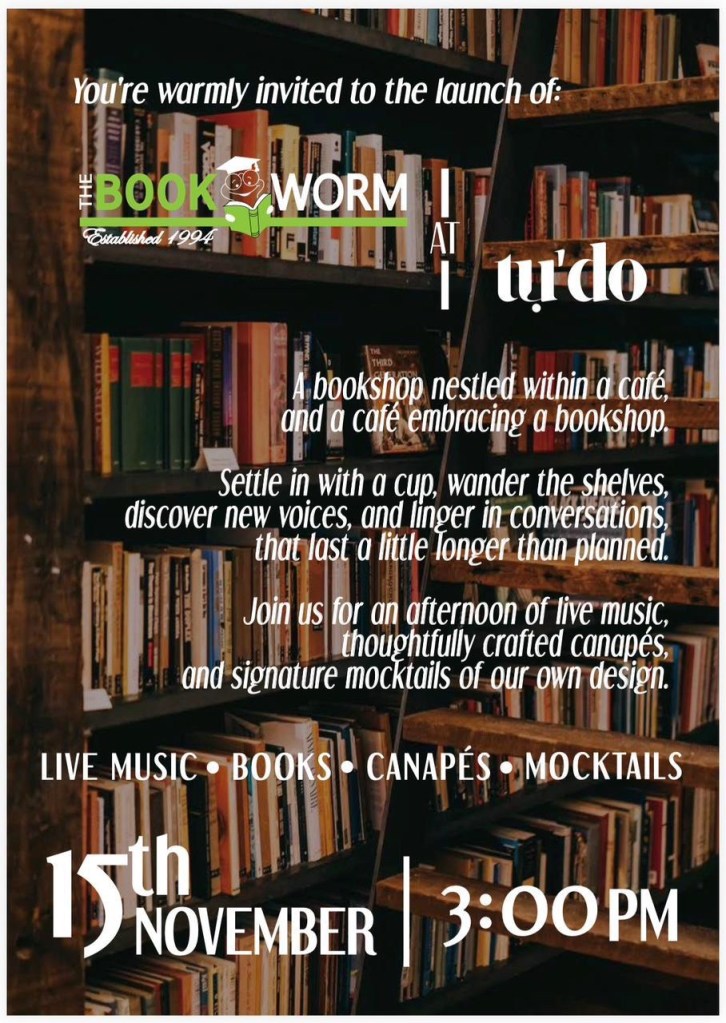

Our featured bookstore’s owner from Bangladesh, Amina Rahman, thinks it can. Rahman of Bookworm, has a unique perspective for she claims, “A lot of people mistake success with earning huge profits… I get fulfilment out of other things –- community health and happiness and… just interaction.” She provides books from across the world and more while trying to create an oasis of quietude in the busy city of Dhaka. It was wonderful listening to her views — they sounded almost utopian… and perhaps, therefore, so much more in synch with the ideas we host in these pages.

Our content this month are like the colours of the rainbow — varied and from many countries. They ring out in different colours and tones, capturing the multiplicity of human existence. The translations start with Professor Fakrul Alam’s transcreation of Nazrul’s Bengali lyrics in quest of the intangible. Isa Kamari translates four of his own Malay poems on spiritual quest, while from Balochi, Fazal Baloch bring us Munir Momin’s esoteric verses in English. Snehprava Das’s translation of Rohini K.Mukherjee poetry from Odia and S.Ramakrishnan’s story translated from Tamil by B.Chandramouli also have the same transcendental notes. Tagore’s playful poem on winter (Sheeth) mingles a bit for spring, the season welcomed by all creatures great and small.

John Valentine brings us poetry that transcends to the realms of Buddha, while Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Ron Pickett and Saranyan BV use avians in varied ways… each associating the birds with their own lores. George Freek gives us poignant poetry using autumn while Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal expresses different yearnings that beset him in the season. Snehaprava Das and Usha Kishore write to express a sense of identity, though the latter clearly identifies herself as a migrant. Young Debadrita Paul writes poignant lines embracing the darkness of human existence. Joseph C. Ogbonna and Raiyan Rashky write cheeky lines, they say, on love. Mohit Saini interestingly protests patriarchal expectations that rituals of life impose on men. We have more variety in poetry from William Doreski, Rex Tan, Shivani Shrivastav and John Grey. Rhys Hughes in his column shares with us what he calls “A Poem Of Unsuccessful Excess” which includes, Ogden Nash, okras, Atilla the Hun, Ulysees, turmeric and many more spices and names knitting them into a unique ‘Hughesque’ narrative.

Our fiction travels from Argentina with Fabiana Elisa Martínez to light pieces by Deborah Blenkhorn and Priyanjana Pramanik, who shares a fun sketch of a nonagenarian grandma. Sreenath Nagireddy addresses migrant lores while Naramsetti Umamaheswararao gives a story set in a village in Andhra Pradesh.

We have non-fiction from around the world. Farouk Gulsara brings us an unusual perspective on festive eating while Odbayar Dorj celebrates festivals of learning in Mongolia. Satyarth Pandita introduces us to Emil Cioran, a twentieth century philosopher and Bhaskar Parichha pays a tribute to Professor Sarbeswar Das. Meredith Stephens talks of her first-hand experience of a boat wreck and Prithvijeet Sinha takes us to the tomb of Sadaat Ali Khan. Ahmad Rayees muses on the deaths and darkness in Kashmir that haunt him. Devraj Singh Kalsi brings in a sense of lightness with a soupçon of humour and dreams of being a fruit seller. Suzanne Kamata revisits a museum in Naoshima in Japan.

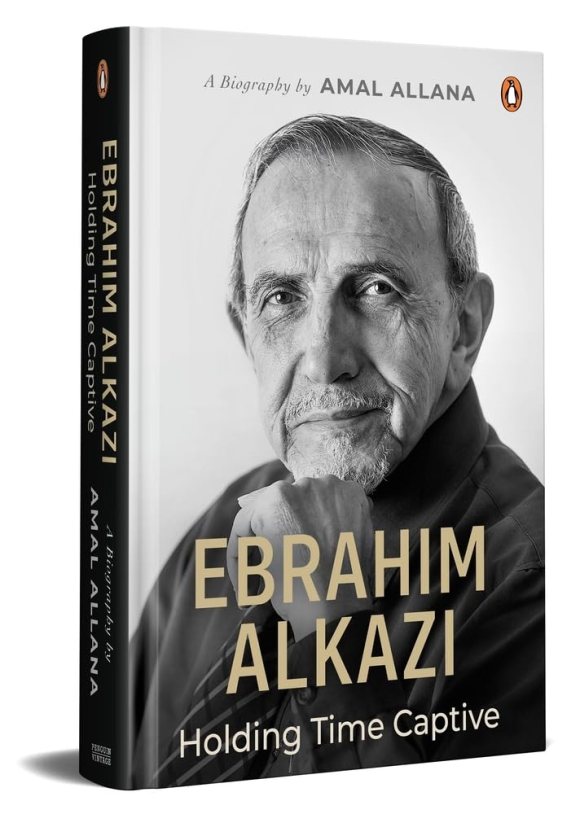

Our book excerpts are from Anuradha Kumar’s sequel to The Kidnapping of Mark Twain, Love and Crime in the Time of Plague: A Bombay Mystery and Wayne F Burke’s Theodore Dreiser – The Giant, a literary non-fiction. Our reviews homes Somdatta Mandal discussion on M.A.Aldrich’s Old Lhasa: A Biography while Satya Narayan Misra writes an in-depth piece on Amal Allana’s Ebrahim Alkazi: Holding Time Captive. Anita Balakrishnan weaves poetry into this section with her analysis of Silver Years: Senior Contemporary Indian Women’s Poetry edited by Sanjukta Dasgupta, Malashri Lal and Anita Nahal. And Parichha reviews Diya Gupta’s India in the Second World War: An Emotional History, a book that looks at the history of the life of common people during a war where soldiers were all paid to satiate political needs of powerbrokers — as is the case in any war. People who create the need for a war rarely fight in them while common people like us always hope for peace.

We have good news to share — Borderless Journal has had the privilege of being listed on Duotrope – which means more readers and writers for us. We are hugely grateful to all our readers and contributors without who we would not have a journal. Thanks to our wonderful team, especially Sohana Manzoor for her fabulous artwork.

Hope you have a wonderful month as we move towards the end of this year.

Looking forward to a new year and spring!

Mitali Chakravarty

CLICK HERE TO ACCESS THE CONTENTS FOR THE NOVMBER 2025 ISSUE.

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.