Ratnottama Sengupta writes she does not junk all the old Calendars and Diaries…

The dawn of every New Year brings with it the need for a new calendar and a couple of new diaries. So, wholesale markets in every major city on the map flourishes with these items in every shape and size. In the years of my growing up, a government organisation calendar, with only the dates and simply no illustration, was routine. Forget 12 images for as many months, even half that number was a rarity. This, even though in the previous decades Raja Ravi Varma’s [1] evocation of Saraswati, Shakuntala, Nala Damayanti or Lady with a Lemon, were coveted adornment for the walls. In certain instances, these images were individually dressed up with sequins and pearls too! Oleographs and mechanical reproductions had, by this time, won past hand paintings that once covered the mud-plastered walls with stories of Ram-Sita Vivaha[2], among others.

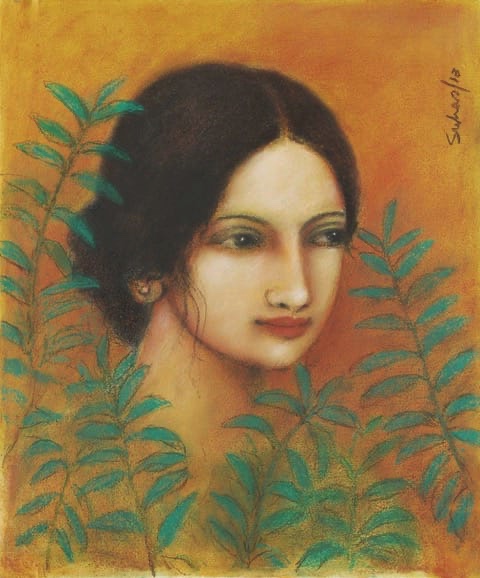

Since the turn of this century, which saw dealings in art skyrocket, galleries have made it a custom to bring out calendars on either a theme that’s tackled by a number of artists, or on works by one chosen artist. Simultaneously artists themselves became proactive in bringing out calendars sporting images of their own work. These are not driven so much with the need to publicise their creativity as to lend a personal touch to the annual give and take of ‘Season’s Greetings’.

I particularly cherish the textile scrolls published annually as calendar by my friend Subrata Bhowmik, one of India’s leading graphic designers. This ‘Design Guru’ has eighteen awards from the President for accomplishments in textiles, publications, advertisement, photography and craft communication. He was motivated to do these calendars in order to share what he learnt in Switzerland as also from his experience in the Calico Museum of Ahmedabad. And they spread a deep understanding of the contextual framework of design in the real world. I still cherish one such tapestry designed with Ajanta style beauties, though the year rang out seven years ago.

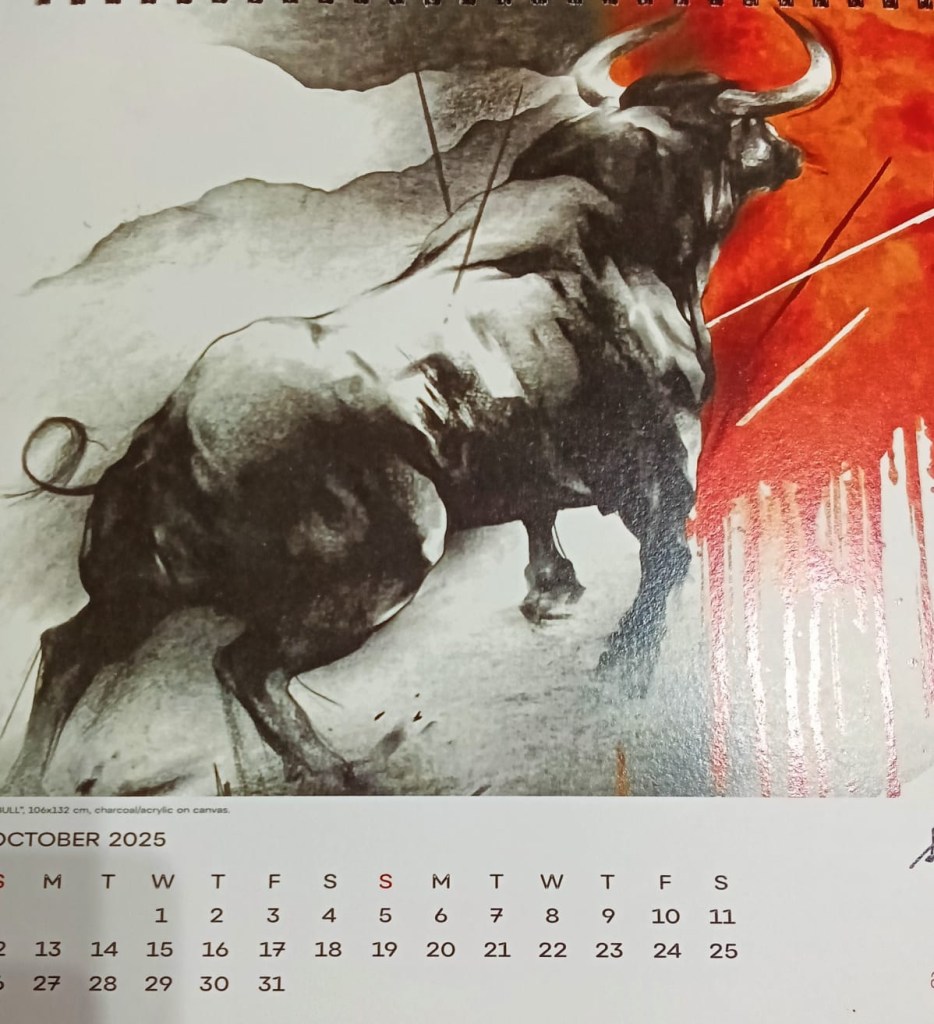

My friend Jayasree Burman’s desk calendar with detailed images of Laxmi Saraswati or Durga have, likewise, remained in my collection years past their expiry dates. Sohini Dhar used to regularly commemorate the memory of husband Ramlal Dhar with images of his landscape that shared pages with her own Bara Maasa, miniature style narration of the seasons. Ajay De’s limited-edition calendar published by Art and Soul gallery this January is in line with this custom.

The passion in Ajay’s charcoal paintings of bulls and the stamina of his stallions bring to mind the energy of Assam’s wild boars that Shyam Kanu Borthakur familiarised; the vitality of the horses Sunil Das studied in Kolkata’s stables; the vigour of Husain’s much auctioned equines; even the animation of Paris-based Shahabuddin’s abstractions. However, the amazing vibrancy of Ajay’s treatment of a black and white palette acquires a touch of magic, with a red dot here or a wash of yellow there. And when he places the charging bull against a wall dripping the salsa red of blood, I recall the vivacity of a ‘Bull Fight’ that I had a chance to witness in Southern France a quarter century ago – before its forceful evocation in Pedro Almodovar’s Talk To Her (2002).

*

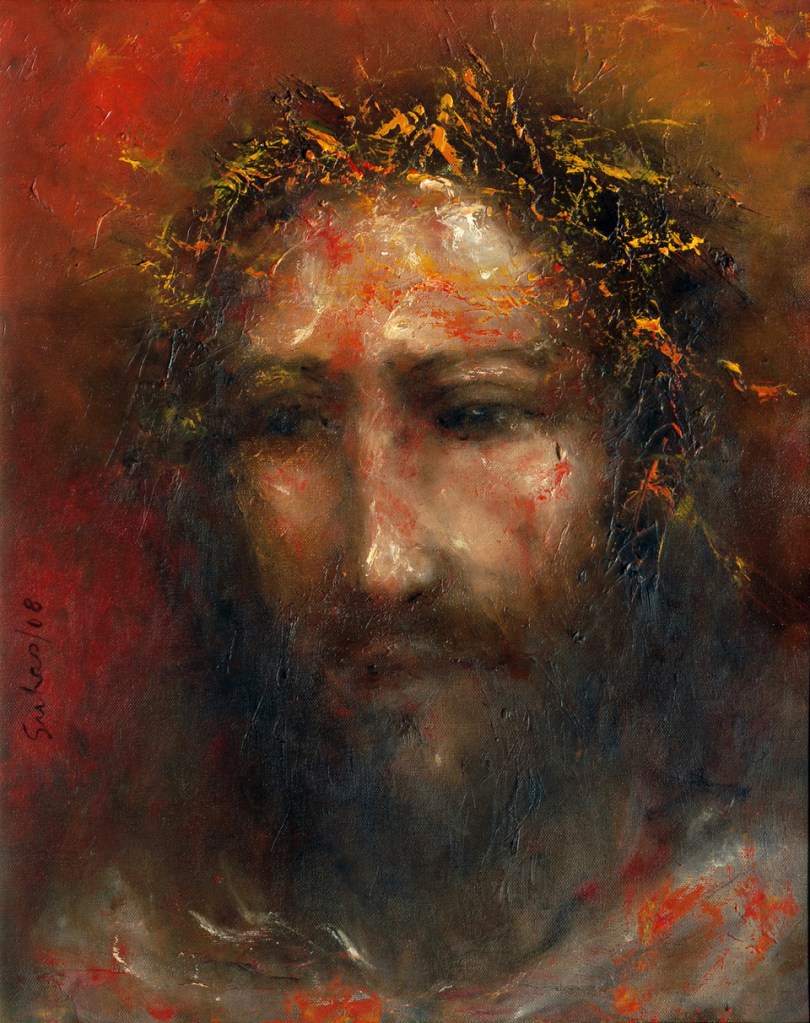

Prabal Chand Boral, as his name suggests, boasts kinship with Raichand Boral, a pioneer of Indian film music in 1940s. Not surprising that Prabal oftentimes breaks into songs on the terrace of his Kolkata home. Every Durga Puja finds him dancing with earthen dhunuchi[3]. And his diurnal routine finds him painting. Sketching. Outlining. Portraits. Flowers. Supernatural creatures. Illusive figures. Capricious forms. He creates videos to involve attentive viewers. And every year, out of his own pocket he brings out a wall calendar for private collection. “An artist craves to express himself in so many ways,” he told me last year when his calendar had sported six portraits in his signature style.

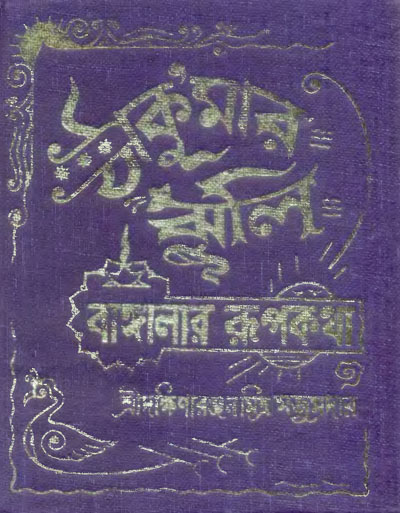

This year Prabal pays an ode to Thakurmar Jhuli (Grandma’s Satchel). Written in 1907 – year 1314 of Bengali calendar — by Dakshina Ranjan Mitra Majumdar this landmark in Bengal’s pre-Independence literature compiles stories that have been orally handed down from one generation to another in the villages and backwaters of undivided Bengal. This was in the manner of the Brothers Grimm who wrote and modified Germanic and Scandinavian tales that have been translated, like Hans Christian Andersen, into every language spoken in the world. In the process they embedded in the collective consciousness of the West lessons of virtue and resilience in the face of adversity.

Much like them Dakshina Ranjan had gone around mechanically recording the tales of Lalkamal Neelkamal, Buddhu Bhutum, Dalim Kumar and Byangoma Byangomi. When first published, Nobel Laureate Rabindranath had written the foreword because he felt that publication of these legends was a need of the hour in order to counter the sense that only the European rulers had fairies, elves and ogres, imaginary beings with magical powers, to entertain and educate their young. Educate? Yes, because the dark and scary beings, even when they did not metamorphose like the Frog Prince, were metaphors for a state where the victim, though less powerful, always overcame the tormentor. Not only children and young adults but grown-ups too liked the stories that broke down the boundaries of time and culture. They encouraged and even emboldened the readers to look for wonder in their own lives.

Prabal had long cherished the desire to reinterpret the illustrations by Dakshina Ranjan himself. He has brought this to fruition with a touch of his own imagination. The result might not be a fairy tale – read, decorative – but none can deny the originality of this calendar.

*

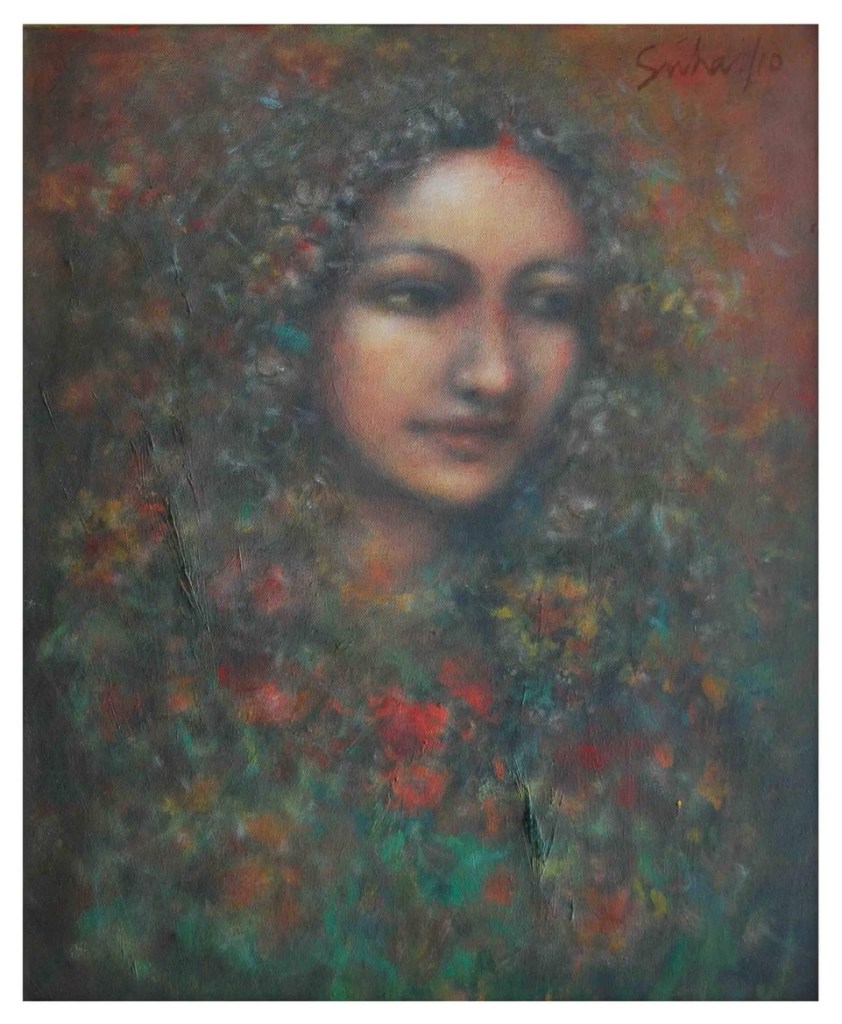

I have personally felt happy to write for a diary – rather, a notebook – that has been published by Nostalgia Colours, a Kolkata based gallery that holds an annual exhibition in other metros of India. A number of the 17 exhibited artists are no longer with us in existential terms. K G Subrmanian, Paritosh Sen, Suhas Roy, Sunil Das, Robin Mondal, Prakash Karmakar — they do not eat-drink-chat with us across the dining table as they once did. Or as Anjolie Ela Menon, Jogen Chowdhury, Ganesh Haloi, Subrata Gangopadhyay and Prabhakar Kolte still do. But their watercolours and gouaches, contes and temperas continue to bring us as much pleasure as when these majors of art signed off their canvases. Only our viewing now is tinged with a certain sadness at the thought that they will no longer add new dimensions to Indian contemporary art scene with their thoughts, their arguments and their palette.

This precisely is what heightens the joy of an undated notebook richly decorated with aesthetic reproductions of not six or twelve but 52 works of art.

A thing of beauty, be it a calendar, a diary or a notebook, is joy forever. Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906) can vouch for that.

.

[1] Raja Ravi Varma, an artist from the nineteenth century who mingled Indian and European styles

[2] Marriage

[3] Bengali incense burner

.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and write books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International