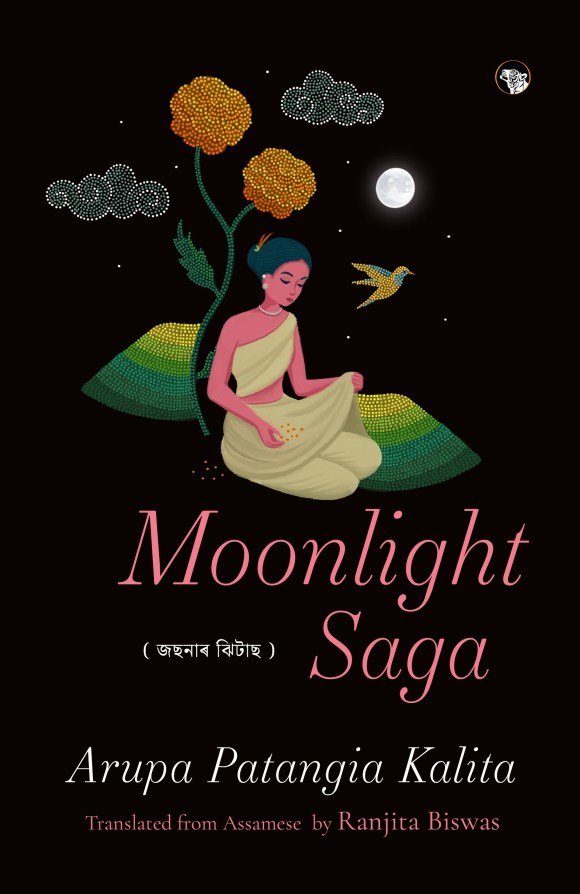

Title: Moonlight Saga

Author: Arupa Kalita Patangia

Translated from Assamese by Ranjita Biswas

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

Many, many years ago, even before time could be stamped with a number, our earth was absolutely empty. The utter silence depressed Singh Buga, the Adi devata—the First God. He could not live in peace in his heavenly abode. So Singh Buga decided to use his magical power to fill up the void with living things. But there was no soil on which they could be nurtured. Water, water, that’s all he saw everywhere. Yes, there was soil under the water, but who could bring it up from such depths? If only he could get some earth, even a small amount, he would fill it with trees and flowers, animals and other living beings. He thought and thought and then he created a leech, a crab and a tortoise. The leech was sent first to get some soil, but he failed in his mission. How could he go down to such great depths under the water? So, Singh Buga sent the crab. But for him too, the soil was too down below. At last, he sent the tortoise. The tortoise followed his Lord’s command and plunged in. He swam far into the depths, reached the bottom and touched the earth’s core. He smelled the earth, took a deep breath, rubbed some of the earth on his body, dug up some more that lay almost inert for eons under the cold water and carried it back for his Lord. Singh Buga was delighted and soon created all the things he desired. The earth that had lain lifeless underwater for thousands of years was touched by sunlight. Wind blew over it. It became full of life. The fertile land became green and spread to the horizon. Plants flowered, trees bowed down with the weight of ripe fruits. The earth was now full of colour. The God decided to create living beings. The calls of birds, animals and insects broke the silence. A pair of milk-white swans laid two eggs. From them Singh Buga created a pair of humans—a man and a woman. He was elated that men would now inhabit the earth. He let them live in a cave and waited with bated breath for news of a new arrival. But where was the news? He waited and waited, finally feeling crestfallen. The pair were very happy roaming around in the beautiful land, but they were ignorant about the mystery of creating life themselves. So, he made them drink laopaani—rice wine—to make their bodies throb with desire.

See that couple sitting morosely in a corner on the ferry? They are no older than the young couple Singh Buga had created out of two swan eggs. But this young couple exudes no sense of happiness. They belong to this burdensome earth; not for them the serenity of the pristine world that God Singh Buga had created. True, they worship him, but in their lives there is only pain and sorrow. Hunger and the torment of a painful existence has chased them every moment. Lack of peace and resentment towards their lot were their constant companions. Adi devata could intoxicate the young couple he had brought to life with liquor and generate in them a desire to create. But for this couple, even if God Singh Buga offered them the best drink, he would only lull them physically from the pain; he would be unable to awaken in them the ancient hunger of the body. Their minds were as dry as the drought-affected earth. On that famished land, only hot tears trickled down drop by drop. The hungry earth sucked in those tears instantly.

The girl, at the cusp of youth, looked utterly dejected. The long arduous journey had drained her energy. Her eyes shut, she rested her head on the shoulder of the equally exhausted young man sitting next to her. If she opened her eyes, the bright sunlight playing on the river’s surface dazzled her and made her head spin. She was too weak to move much.

Her name was Durgi. Durgi Bhumij. An expert sculptor seemed to have lovingly carved her figure. Her statuesque body had thinned down somewhat, but strangely, though wreaked by hunger and thirst, her light brown face had not lost its charm. She was, after all, Durgi—Durga mai, Goddess Durga. She was born during the autumn festival of Durga puja, when the throbbing madal drum was beating frenziedly outside their house. Her grandmother cut the umbilical cord, gave the baby a bath and placed her on her mother’s breast and said, ‘Durga mai has come to our house.’ The old woman named her Durgi in the likeness of the Shakti Goddess.

But now, her granny’s beloved Durga mai was facing terrible times. A devastating famine had crippled their land of red earth. Its canopy of forests of mahua, sal and teak were now filled with only heart-rending cries from hungry mouths, and death.

Durgi was at an age when she could digest even chips of stone. But there was nothing to eat. The fields lay dry. The white sahibs had taken away everything. There was no water in the river for them, no forests to pick fruits from. There was no work: no field to till, no forest to forage for potatoes and yams. Entering the forest for their age-old practice of hunting was banned. As was fishing in the river next to their village. All these now belonged to ‘others’. The only word that echoed through the land was: NOTHING…NOTHING. Nothing was left for them. Rice became as costly as gold.

There had been floods in the past, even droughts. But like a mother whose annoyance with a child does not last long, Mother Nature’s anger also did not carry on forever. The earth became indulgent again, green shoots showed up joyfully once more. But the kind of famine Durgi and her people were now facing was like coming up against a formidable hill they could not surmount…

(Extracted from Moonlight Saga by Arupa Kalita Patangia, translated from Assamese by Ranjita Biswas. Published by Speaking Tiger Books 2026.)

ABOUT THE BOOK

In the lush yet brutal landscape of colonial Assam unfolds a haunting chapter of history—the rise of the tea plantations and the human cost that sustained them. Drawn by promises of Assam desh—a land of dignity, abundance, and fair wages—Adivasi families from central India are packed onto overcrowded steamers and sent upriver, where hunger, disease and death shadow every step of their journey. Among them is Durgi, a young woman whose resilience endures even in despair. With her, she carries a small bundle of marigold seeds, a fragile memory of the land of red earth she has left behind. At her side is her husband, Dosaru, the rebellious archer, bound to her by love and the shared hope of building a life of their own. However, what awaits them at Atharighat Tea Estate is no promised land. Labourers are stripped, disinfected, confined to barracks, and driven into relentless work, while sickness, fear, and muted defiance simmer beneath the ordered rows of tea bushes.

Durgi’s life takes a complicated turn over the years—an intimate affair with Fraser, the white manager of the tea garden, results in the birth of three mixed race children. Their unequal relationship exposes another unspoken truth about plantation life—the generations of similar children, many of whom, abandoned by their white ancestors, still live in Assam’s tea gardens today.

Rooted in lived experience, Moonlight Saga gives voice to the forgotten men and women who built the empire’s ‘green gold’, bearing witness to their suffering, endurance, and fragile hopes—as the British Raj begins to crumble in the shadows of India’s Independence struggle.

Originally written in Assamese, the novel is a celebrated and much-discussed work in Assam, recognised for its unflinching portrayal of plantation life and its place in the region’s collective memory. Its translation into English opens up an essential regional story to a wider readership, ensuring that the sacrifices and struggles embedded in the tea gardens are not forgotten.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Arupa Kalita Patangia is one of the best-known Assamese writers of today. She has five novels, twelve short story collections, several novellas, books for children, and translations into Assamese to her credit. In 2014, she received the prestigious Sahitya Akademi Award for her book of short stories, Mariam Austin Othoba Hira Barua.

ABOUT THE TRANSLATOR

Ranjita Biswas is an independent journalist, fiction and travel writer, and translator. Ranjita has won the KATHA translation awards several times. She has also to her credit eight published works in translation.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL