It is a truth almost universally acknowledged that Jane Austen is a great writer. The world created by her in just six novels continues to regale generations of readers with tales of love, marriage and money, a sentiment which would be reiterated by substantial numbers of her fans all over the globe. We could well echo Evelyn Waugh on the comic writer P. G. Wodehouse: that his (Wodehouse’s) inimitable world could never grow stale….that he has made a world for us (readers) to live in and delight in…

Jane Austen(1775-1817) has acquired a kind of cult status in the last couple of centuries. Such is her reputation that it has helped birth a veritable Jane Austen industry, replete with museums, memorabilia and mementos. There have been numerous novels and films inspired by Pride and Prejudice and Emma and many films (and remakes and adaptations) based on her novels.

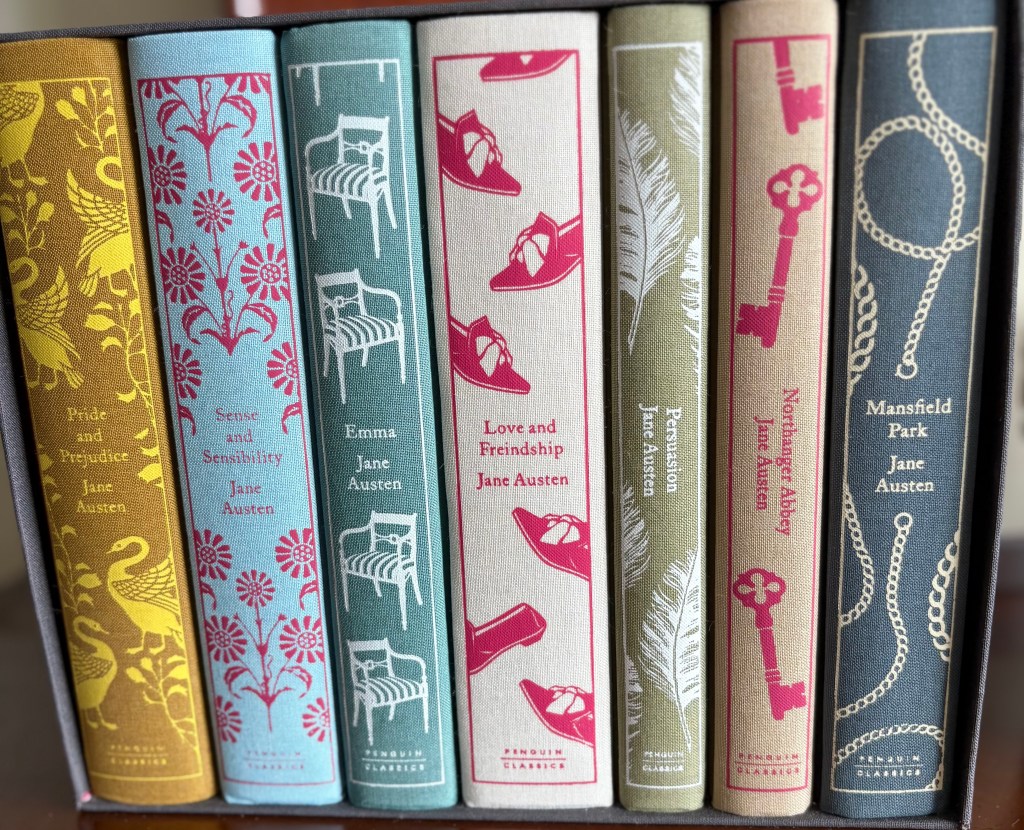

16 December 2025 marks her 250th birth anniversary. Many museums in the UK and the USA have showcased exhibits which give viewers delightful glimpses into her life and writing. Her novels, full of wit and satire, provide an insightful commentary on the social hierarchies, as well as the quirks and oddities of her milieu.Their plots and themes are woven around women and the necessity of marriage, money and the determining power of money.With considerable irony and subtlety, she turns the mirror on how manners are a function of morality and good sense and not just a matter of appearances. Rarely didactic or preachy(with Mansfield Park as the only exception), her novels convey in perfectly nuanced and measured prose, how difficult and crucial it is for women to find the right spouse and space.

As the youngest daughter of a poor clergyman, mostly educated at home, Jane Austen was well aware of the value of an independent income and a home of their own. After the death of her father, she, her sister Cassandra and mother, rather like the Dashwood women in her novel Sense and Sensibility, had to move around as they were dependant on the financial support of her brothers, especially her wealthy brother, Edward. The pain of this unequal fortune and frequent shifts, which Jane and her sister Cassandra may have experienced, is expressed by Elinor and Marianne in the novel where they have to practice small economies and learn to scale their expectations according to their situation.

Austen led a largely sheltered and sequestered existence, surrounded by her family, bound to family duties which “might have been the more expected of a dependent spinster aunt such as she was.”[1] Many intelligent women, like Charlotte Lucas, Elizabeth Bennett’s friend in Pride and Prejudice are shown to accept inferior matches to escape from spinsterhood and the expectations of their natal families. The absence of livelihood opportunities for women in her day and the lack of any income of her own would have proved irksome to Austen and provided her with a further impetus to “write her way into some money,” as she wrote in a letter to her brother, Captain Francis Austen, in July 1813. Further, in another letter to her niece Fanny Knight, she writes that “single women have the propensity to be poor which is one very strong inducement for women to marry.”

Her novels often do not always reveal the full measure of Jane Austen’s remarkable achievement: how she, constrained by genteel poverty, “the lack of a room of her own”, and writing materials which had to be put away often to attend to obligatory family commitments, wrote her novels based on such close observation of, and acute insight into contemporary life. Her eye for detail is such that it invites frequent references to her own words: “A little bit of ivory, two inches wide, on which I work with a brush so fine as to produce little effect after much labour.” This modest disclaimer and “little effect” have, however, fascinated generations of readers and inspired hosts of writers.

That Jane Austen’s 250th anniversary is being celebrated and commemorated all over the English-speaking world perhaps comes as no surprise but it still leaves us with some questions. What is the relevance of her novels now? Are her novels relevant to present-day political realities, in addition to their astute observations on graded social hierarchies? Can we view her as a feminist? Does she merit inclusion and study in universities of the global south at a time when there is a strong drive to decolonise English, the language of the erstwhile colonial masters?

In her book Jane Austen: The Secret Radical, Helena Kelly writes of the subversive and radical potential and intent of Jane Austen’s novels. Kelly goes a step beyond Marilyn Butler’s 1987 Jane Austen and the War of Ideas that had suggested that Austen leaned on the conservative Burkean side when challenged by new-fangled Jacobinism with its ideas of equality and brotherhood, coming from France which disturbed hierarchies, ideas and values long held to be sacrosanct in traditional English society. Kelly suggests that far from being conservative, insulated from contemporary political concerns, Jane Austen held radical and possibly subversive views which she did not express openly but which are clearly configured in the world of her novels. In doing so, she made the novel a meaningful art-form and a vehicle for the expression of ideas around love, marriage and additionally also of debates on slavery, female education and emancipation.

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in the want of a wife.”[2] This famous ironic opening sentence of Austen’s has captured attention and elicited many critical commentaries. It’s a brilliant masterstroke where Austen underlines the mindset of young women and their anxious mothers on the lookout for eligible bachelors. Articulated like a truism, it seeks to facetiously universalise a partial truth. The omniscient authorial tone and tenor encompasses the dominant themes of Pride and Prejudice in the opening statement itself. Marriage, women’s responses, men’s reactions, social rank and wealth — all the principal subjects of Austen’s writing are near universal themes. In her novels, Austen communicates the constraints within which women function and the limited or literally the only ‘choice’ available to them. Having experienced financial instability and economic dependence, she had a clear understanding of the constraints experienced by women in early nineteenth-century England.

The happy ending that we see where Elizabeth Benett indeed becomes “mistress of Pemberley” symbolises the moment when some women, having acquired a certain status, become custodians of the home and the private sphere. Some feminist historians like Gerda Lerner, however, have pin-pointed this moment as one where the economic marginalisation of women is complete, in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, and they are pushed back from the public sphere.

Even as women were participating in print culture and taking their place as readers and writers, they were increasingly relegated to the private sphere. The tendency to relegate women to the private sphere and making them responsible for the entire range of domestic tasks of nurturing and care-giving and thereby sustaining the edifice of domestic life is something that persists even now. The fact is that women’s participation in the paid economy and public sphere has added to their ‘double’ burden in the 21st century.

Many critical voices have pointed out that Jane Austen’s writings do not directly mention the political situation, philosophical debates or religious discourses of the day centering on questions of social equality, justice, economic questions or the rights of man. Yet her fine crafted depiction of socio-economic relations, the dynamics of human relationships shaped and moulded by the struggle for wealth or power or status exposes the political reality, social hierarchy and the economic structure in society which shaped and informed all social transactions.

While the position of women may have improved in some spheres, there are still glaring gaps when it comes to women’s access to equality or justice. Changes in the last two centuries have gone beyond superficial tokenism. There are still miles to go in our march towards equality. It is in this larger context where there is a grudging acceptance or disavowal of women’s rights that the Jane Austen heroine’s negotiations with patriarchy remain relevant.

They demonstrate a mode of assertion, of agency in the face of inequality and in socially disadvantaged situations, which sustain an illusion of female empowerment and wish-fulfilment. It is this vision of romance, which, informed by a comic and somewhat ironical view of life, consolidates the exercise of female agency and makes the reading and re-reading of Jane Austen’s novels a rewarding and enriching experience. Her astute delineation of human delusion and human folly holds up a mirror to her society that often impels recognition on our part and remains forever relevant. Her perceptive analysis of the warp and weft of her society remains almost unmatched.

To recall Auden’s well-known lines on Jane Austen:

…yet he (Byron) cannot match the shock she (Austen) gives me;

Beside her, Joyce is as innocent as young grass. I feel truly uneasy, my mind unsettled,

Watching the English middle-class spinster

describe the power of money to attract love,

so plainly and soberly revealing

the economic foundations that sustain human society.

W.H.Auden’s lines on Jane Austen and the unlikely comparison with the prince of notoriety, Lord George Byron, never fails to instruct or entertain us. Such is the mark of great literature which leaves its imprint decades and centuries after its inception.

[1] Juthika Patankar, Wire, November 2025

[2] Pride and Prejudice

Meenakshi Malhotra is Professor of English Literature at Hansraj College, University of Delhi, and has been involved in teaching and curriculum development in several universities. She has edited two books on Women and Lifewriting, Representing the Self and Claiming the I, in addition to numerous published articles on gender, literature and feminist theory. Her most recent publication is The Gendered Body: Negotiation, Resistance, Struggle.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International