Narrative and photographs by Mohul Bhowmick

Young lamas, or monks, appearing for their annual examinations in the monsatry of Simtokha Dzong, Thimphu.

Bhutan, 2024

The sun sets far too quickly for my liking in Phuentsoling. There is little to no entertainment to speak of that is worth its name. The town, by and large, presents itself in its entirety and goes to bed by the time my friend, S, and I crisscross our way to our hotel uphill. It does not help that we enter Bhutanese soil on its National Day, celebrated to mark the coronation of their first king Ugyen Wangchuk in 1907, and find most places of public convenience closed.

The stark contrast that the Indian border town of Jaigaon offers to its Bhutanese counterpart Phuentsoling is remarkable. The lack of men — and their wherewithal — on crossing the north-eastern frontier is welcome, as is the steep upkeep that the Himalayan kingdom pushes upon its citizens.

*

The Phuentsoling-Thimphu highway has improved by leaps and bounds since Queen Mother Ashi Dorji Wangmo Wangchuck made her initial foray into the hills of Kalimpong from the village of Nobgang in the 70s. I try my best to spot a mule — or its track — but am left disappointed by the presence of a modern-day state-of-the-art business college in Gedu[1] instead.

The lower reaches of the Himalayas that surround us to the east act as forbidding barriers into the hidden crevices of the hidden kingdom we are attempting to climb in a motor vehicle, the likes of which were first seen in this country in the 1980s. The light — of which I had been so painfully deprived in Phuentsoling — seeps in with zeal I have seldom seen in the plains of the Deccan, and the lifeblood that flows inside me is roused enough to taste the incandescent flavours of kewa datsi[2]with red rice. And before I know it, a lifelong love affair has begun with this enticing dish.

*

We are welcomed into Bhutan proper only after arriving in Thimphu the next day, or so it seems. The capital city of this virgin kingdom has evolved significantly from Pico Iyer’s assumptions in 1989 that all of it could be explored over the course of an afternoon. That the Druk Hotel in which the legendary essayist stayed remains steadfast beyond the clocktower that shows no change of hands is a testament to the art of stillness that the Bhutanese so pride themselves upon; at 11 AM on a weekday at a laundromat not far from the main street hangs a signboard proclaiming, ‘closed for lunch.’ Iyer is not too far off the mark even thirty-five years later.

That the people smile easily takes me by surprise; I have seldom known a populace so unburdened by the weight of living that they have overtaken all their consternations and settled finally upon the art of being. Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuk, Bhutan’s present king, finds himself immortalised in pictures across every restaurant, hotel and store across the country.

The fervour seems, to me, all the more in Thimphu, where the local masses try to outdo their neighbours in anticipation of the gentle 44-year-old stepping out of the Tashicho Dzong grounds (his palace) to inspect these pictures and possibly reward their owners for their loyalty. I suspect this ardour stems as much from devotion to their ‘living God’ as to the fear of missing out or merely keeping up with the Joneses — or Wangchucks. Some modern predicaments seem to have crept into Druk after all.

It is not without these frailties that one’s mornings in Thimphu are strewed. Gather and scatter, as the bard Vikram Seth[3] was wont to have mentioned, applies less to the hounding of the dogs mid-street all night than to the karaoke bars that pride themselves on staying open when the rest of the world sleeps.

Had Nehru not arrived in Paro from Nathu La in 1958 on the back of a yak, this journey would have seemed almost romantic to that of the least fatalistic of Indian prime ministers. It is not known whether the venerable freedom fighter from Allahabad shared any of his midnight oil burning advice with the Bhutanese during his state visit; it appears for certain that the karaoke bars sprung up like mushrooms much later and took his guiding directions to heart.

*

If it is not the baying of the foolhardy dogs, it is the crowing of the late-night suppliers at the fifty shops selling similar products on the Thimphu main street that keeps me — and my journalistic tendencies — awake. Onitsuka Tiger [4]rubs shoulders with Adidas Samba[5] with a glee that one forsakes in favour of the warmth that a bowl of tofu thukpa [6]offers; before long, a handsome policeman in his impeccable uniform including a heartening jacket and betel-stained teeth joins me for a cup of tea. He has just finished his duty of acting as the traffic signal in a city that has no traffic signals.

With the precision best described as that of mimicking an archer — of whose credulity there is a lot in Bhutan — my newfound friend diverts the few cars that choose to make the hike into Thimphu’s central business district on this cold night. He tells me about how gently the tea goes with the thukpa I have with me, all while seated on the plank of a wooden crate left behind by the Adidas doppelgangers.

A plate of momos — beef for him, and cabbage for me — soon arrives from Kinley Tsering, a lady who sells home-cooked food at night after tending to her household all day to augment the family income. In a horror mixed with incomprehension of protocol, my friend in livery whips out his wallet to pay; I am stunned by an act I have never seen uniform-clad men do in the past. The temperature plunges to minus six degrees Celsius as I walk back with the numbing, tear-inducing breeze on my face. I feel exhilarated.

*

The Paro airport is considered to be one of the most dangerous places in the world to land in.

Paro[7], imperious, meek and all-abiding, comes too soon and whisks away any perceptible delight that one feels at having escaped the wrath that Thimphu denotes upon those who cannot see. The dzong, located several miles outside of town, is the only real attraction besides the museum on the way down; modern tourists — and locals besides — tend to find enjoyment in climbing up the steep hillocks to gain a view of a Druk Airplane taking flight from what is considered to be among the most dangerous airports in the world. Back on the main strip that connects this valley to Chuyul in the north, dinner consists of dried ema (Bhutanese chilli), vegetables and rice, with accompaniments of dumplings.

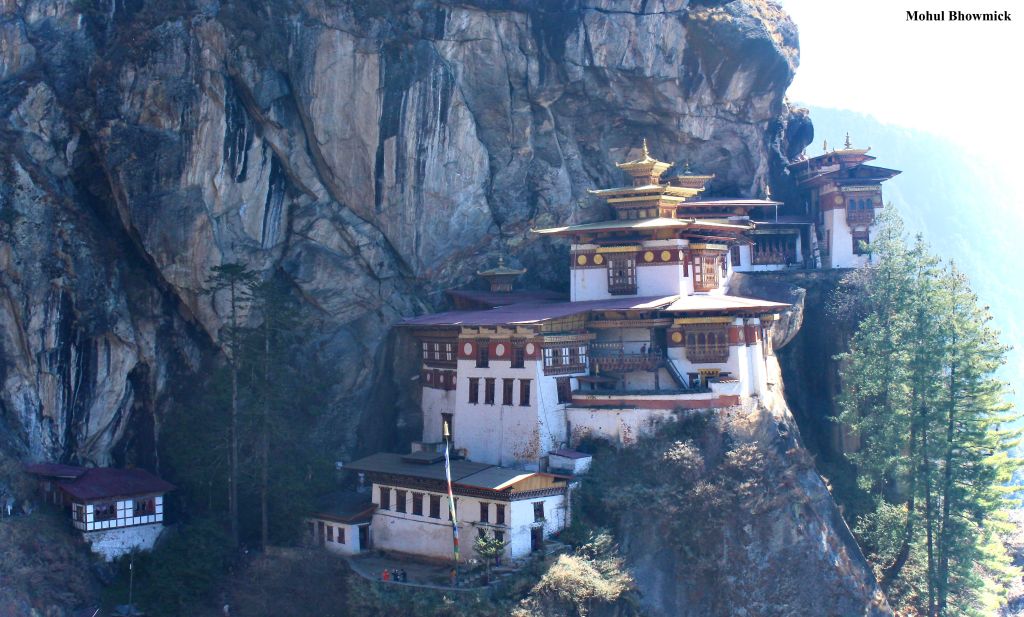

The Taktsang Lakhang[8] stands upright on the shoulder of a cliff the next day; I am perplexed as to how I could be so close as to see the finer details of its inner sanctum in my mind yet far enough to appreciate the impossible angle at which it is perched. The monastery, which had dominated so many of my dreams about Bhutan in the past, is often referred to as the ‘Tiger’s Nest’ by the West. It takes its name from a spot allegedly visited by the Indian guru, Padmasambhava[9], on the back of a mythical flying tiger in the eighth century to flay a demoness who was tormenting the locals of the area.

The climb is demanding, but the panoramic views of the valley to the east make it seem less so. The ardour of the fellow pilgrim is contagious enough for me to push past the mental barriers I have erected for myself without even trying, and before I know it, we are at the halfway point where the government has been kind enough to let an eatery ply its trade. The Local Train’s Vaaqif[10] accompanies us as Taktsang appears all the more closer, and all the more dangerous.

The ascent, dusty and translucent though it is due to the lack of rain for several months, troubles me with its penchant for nonchalance. I loathe to fall into the reverie that takes me over every minute while glimpsing at a branch of the hundred-year-old rhododendron that has stood firm while men have grappled past their anxieties. I awaken soon enough with the realisation that my worries and physical ailments may seem impotent to the staunch Buddhist who makes the six-kilometre hike to the monastery by prostrating himself full-length, getting up and repeating the feat till he gets to the top a week after he has begun.

The top is still way off from where one reaches the monastery proper. Perched dangerously on the edge of this cliff, the monastery virtually hangs into oblivion attracting gusts of wind, who somehow choose not to play to the gallery. Yet, it has survived for centuries, and if faith were one’s sole determinator, it shall survive for several more. The inside has temples dedicated to Padmasambhava in his various forms: astounded, wrathful and compassionate.

Propitiating the gods — and as an extension, their other halves, the demons — is commonplace in Bhutan, and the same holds for ParoTaktsang. While the inordinate thangkas[11] and artefacts collected over the years provide the inner sanctum sanctorum of the monastery with its sheen, it is the historical hostility that the local deities have displayed towards demons that make it eerily attractive. Indeed, folk tales observe that several local, protective deities were demons won over by the Buddhist dharma when Padmasambhava arrived on the back of his mythical tiger.

And so it is that I find myself in the dark, indistinct crevices of the cliff on which the monastery proper is located but beneath which is the original Tiger’s Nest which the Bhutanese claim to have a pug mark of Padmasambhava’s beast. The descent into the darkness, almost as if plunging into the unknown, requires one to be on his back and flatten himself along the rocks to reach the acute angle where the pug mark is located.

A lonely candle blows in this unventilated corner of the cliff, and only a sliver of light to the east remains to remind me of the vast world outside, that which I have forsaken to witness this tiny fraction of hope at Taktsang. This hope flutters unabated, almost as if without any beginning or end, and for a moment, I am suspended in the brilliant sunshine overlooking a valley fit for the heroic landscapes I so fervently pursue. Might this be the only time when I forsake my attachment to life in search of a glorious future, real or imagined?

There is no end to the ruminations that I have while being assailed by the light that peeps in almost as if it is too shy to ask for permission. The way out may be more difficult than the way in — as in life — but how do I respond to the call I have heard inside, the one that compels me to sing the songs of my fathers in the temples of my gods?

The thought strikes with a speed I had not known I possessed until I see the boulder above me swerve in its position in a quarter of a millisecond; with an equal lack of precision and comfort, I come out of the cave, for all the world a dishevelled a youth with an abrasive attitude towards the world, but in my own estimation, a changed man. I did not need new eyes, but merely a new way of seeing.

*

The magnificent Punakha dzong is surrounded by the river Mo Chhu.

The dzong[12] of Punakha is a magnificent object of interest to lovers of history and architecture alike; straddled on an oasis that one must reach after crossing the timid-looking Mo Chhu River, it looms large into the thoughtful sunshine all the while immersed in a meditative calm that only its altitude has any makings of. Like all dzongs in Bhutan, the one in Punakha too is much more impressive from the outside. Tall, gaunt and imperial in its outlook, it acts more as a presence of the godly authority that the king and abbot enjoy in Bhutanese society, the former only matched in his regal bearing by the latter.

Even more impressive, if the word is right, is the suspension bridge that takes one across the river Po Chhu (the male consort of Mo Chhu) behind the dzong. There is little to look at but the other end as one sways with the wind — and the breeze is far too strong for my liking even at three in the afternoon here — while praying to the Gods, both Indian and Bhutanese, that the bridge does not give way and deposit me into the freezing waters of the river about three vertical kilometres below. The 160-metres bridge span seems more than a mile to me; awake finally at the reality of life slipping away from my grasp in the blink of an eye, I experience the innards of a fear that I thought I had buried deep inside myself.

For the entire time that I cross the bridge — and return — for there is nothing to see on the other side but an eatery that sells delightful ice cream, this fear flares in a bid to reignite my passions for a world I had once deeply cared for and strongly felt like changing. For all the lack of consideration that I display, either in terms of material or intangible riches, there is little that stays on par with this kind of fear, the one that reminds me at every step that I am virtually playing with my fate, and that everything I have with me, most perceptibly my heartbeat, could drown in a second if the heavens so choose. A strong gust of wind and I can finally sense what Matthiessen[13] meant when he wrote:

‘This is a fine chance to let go, to win my life by losing it…’

I am driven back to life when a local teenager rides across the heavily swaying bridge and into the sun — with the mildly flowering dandelions emitting a heady scent ideal for such gallant terrains, on his bicycle — too young to care about life’s intricacies, yet old enough to realise that everything one wants is on the other side of fear.

It is in such heroic landscapes that I change my stance towards the heavens; where I drink the water from the stream gurgling past the Po Chhu and gulp in the air that promises a revival of a dream seen long ago. Such dreams deserve their rightful places in a world shorn of temerity in a way that human emotions can seldom fathom. And yet the dandelions, by now competing with the rhododendrons that shall have to wait till spring, promise a tomorrow that may not get swayed by this incredible afternoon breeze.

*

When I wake up a month later in the arid plains of the Deccan, unsure if such dreams are still worth chasing — or life still worth living — I remember that the dandelions would soon be in bloom in the hidden kingdom I so arduously seek within myself.

The gently flowing Paro Chhu river makes one lie down beside it and do nothing.

[1] In Bhutan

[2] A dish made of potatoes and cheese

[3] From Summer Requiem, a book of poems by Vikram Seth

[4] A Japanese fashion brand

[5] A shoe brand

[6] A Tibetan noodle soup

[7] Historic town in Bhutan

[8] Monastery in Paro

[9] Buddhist mystic of the 8th century CE

[10] Song by pop group, Local Train

[11] Buddhist art on cotton

[12] Fort

[13] Peter Mattheissen (1927-2014) novelist, naturalist and CIA Agent

Mohul Bhowmick is a national-level cricketer, poet, sports journalist, essayist and travel writer from Hyderabad, India. He has published four collections of poems and one travelogue so far. More of his work can be discovered on his website: www.mohulbhowmick.com.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International