I flow and fly

with the wind further

still; through time

and newborn worlds…

--‘Limits’ by Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal

In winters, birds migrate. They face no barriers. The sun also shines across fences without any hindrance. Long ago, the late Nirendranath Chakraborty (1924-2018) wrote about a boy, Amalkanti, who wanted to be sunshine. The real world held him back and he became a worker in a dark printing press. Dreams sometimes can come to nought for humanity has enough walls to keep out those who they feel do not ‘belong’ to their way of life or thought. Some even war, kill and violate to secure an exclusive existence. Despite the perpetuation of these fences, people are now forced to emigrate not only to find shelter from the violences of wars but also to find a refuge from climate disasters. These people — the refuge seekers— are referred to as refugees[1]. And yet, there are a few who find it in themselves to waft to new worlds, create with their ideas and redefine norms… for no reason except that they feel a sense of belonging to a culture to which they were not born. These people are often referred to as migrants.

At the close of this year, Keith Lyons brings us one such persona who has found a firm footing in New Zealand. Setting new trends and inspiring others is a writer called Harry Ricketts[2]. He has even shared a poem from his latest collection, Bonfires on the Ice. Ricketts’ poem moves from the personal to the universal as does the poetry of another migrant, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal, aspiring to a new, more accepting world. While Tulip Chowdhury — who also moved across oceans — prays for peace in a war torn, weather-worn world:

I plant new seeds of dreams

for a peaceful world of tomorrow.

--‘Hopes and Dreams’ by Tulip Chowdhury

We have more poems this month that while showcasing the vibrancy of thoughts bind with the commonality of felt emotions on a variety of issues from Laila Brahmbhatt, John Grey, Saba Zahoor, Diane Webster, Gautham Pradeep, Daniel Gene Barlekamp, Annwesa Abhipsa Pani, Cal Freeman, Smitha Vishwanath, John Swain, Nziku Ann and Anne Whitehouse. Ramzi Albert Rihani makes us sit up by inverting norms while Ryan Quinn Flangan with his distinctive style raises larger questions on the need for attitudinal changes while talking of car parks. Rhys Hughes sprinkles ‘Hughesque’ humour into poetry with traffic jams as he does with his funny spooky narrative around Christmas.

Fiction in this issue reverberates across the world with Marc Rosenberg bringing us a poignant telling centred around childhood, innocence and abuse. Sayan Sarkar gives a witty, captivating, climate-friendly narrative centred around trees. Naramsetti Umamaheswararao weaves a fable set in Southern India.

A story by Nasir Rahim Sohrabi from the dusty landscapes of Balochistan has found its way into our translations too with Fazal Baloch rendering it into English from Balochi. Isa Kamari translates his own Malay poems which echo themes of his powerful novels, A Song of the Wind (2007) and Tweet(2017), both centred around the making of Singapore. Snehaprava Das introduces Odia poems by Satrughna Pandab in English. While Professor Fakrul Alam renders one of Nazrul’s best-loved songs from Bengali to English, Tagore’s translated poem Jatri (Passenger) welcomes prospectives onboard a boat —almost an anti-thesis of his earlier poem ‘Sonar Tori’ (The Golden Boat) where the ferry woman rows off robbing her client.

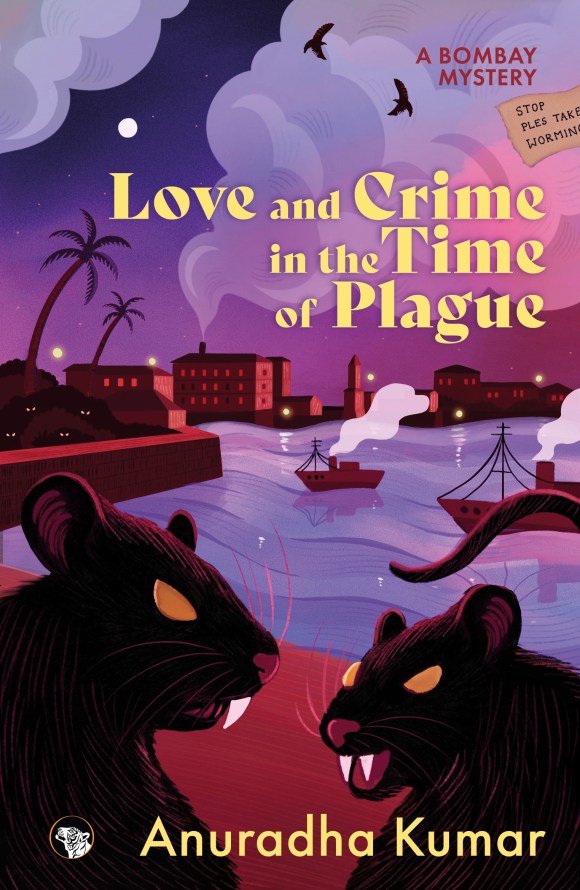

In reviews, we also have a poetry collection, This Could Be a Love Poem for You by Ranu Uniyal discussed by Gazala Khan. Bhaskar Parichha introduces a book that dwells on aging and mental health issues, Indira Das’s Last Song before Home, translated from Bengali by Bina Biswas. Rakhi Dalal has reviewed Anuradha Kumar’s Love and Crime in the Time of Plague:A Bombay Mystery, a historical mystery novel set in the Bombay of yore, a sequel to her earlier The Kidnapping of Mark Twain. Andreas Giesbert has woven in supernatural lore into this section by introducing Ariel Slick’s The Devil Take the Blues: A Southern Gothic Novel. In our excerpts too, we have ghostly lore with an extract from Ghosted: Delhi’s Haunted Monuments by Eric Chopra. The other excerpt is from Marzia Pasini’s Leonie’s Leap, a YA novel showcasing resilience.

We have plenty of non-fiction this time starting with a tribute to Jane Austen (1775-1817) by Meenakshi Malhotra. Austen turns 250 this year and continues relevant with remakes in not only films but also reimagined with books around her novels — especially Pride and Prejudice (which has even a zombie version). Bhaskar Parichha pays a tribute to writer Bibhuti Patnaik. Ravi Varmman K Kanniappan explores ancient Sangam Literature from Tamil Nadu and Ratnottama Sengupta revisits an art exhibition that draws bridges across time… an exploration she herself curated.

Suzanne Kamata takes us on a train journey through historical Japan and Meredith Stephens finds joy in visiting friends and living in a two-hundred-year-old house from the Edo period[3]. Mohul Bhowmick introduces a syncretic and cosmopolitan Bombay (now Mumbai). Gower Bhat gives his opinion on examination systems in Kashmir, which echoes issues faced across the world while Jun A. Alindogan raises concerns over Filipino norms.

Farouk Gulsara — with his dry humour — critiques the growing dependence on artificial intelligence (or the lack of it). Devraj Singh Kalsi again shares a spooky adventure in a funny vein.

We have a spray of colours from across almost all the continents in our pages this time. A bumper issue again — for which all of the contributors have our heartfelt thanks. Huge thanks to our fabulous team who pitch in to make a vibrant issue for all of us. A special thanks to Sohana Manzoor for the fabulous artwork. And as our readers continue to grow in numbers by leap and bounds, I would want to thank you all for visiting our content! Introduce your friends too if you like what you find and do remember to pause by this issue’s contents page.

Wish all of you happy reading through the holiday season!

Best wishes,

Mitali Chakravarty

CLICK HERE TO ACCESS THE CONTENTS FOR THE DECEMBER 2025 ISSUE.

[2] Harry Ricketts born and educated in England moved to New Zealand.

[3] Edo period in Japan (1603-1868)

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.