Story by Bitan Chakraborty, translated from Bengali by Kiriti Sengupta

The black smoke rises in a straight line. It will fade into the air as it reaches a certain altitude in the sky. The wind feels still today, causing a grey layer to form. Not long ago, Lali experienced recurrent bouts of excruciating pain, but now it refuses to subside. She tries to relax, her spine loosely resting against the wall of the leather factory. Lali shrinks again as her little baby stretches its limbs inside her womb. In the distance, her husband, Fatik, is tending to their domestic belongings in the dilapidated house. He is vigilant, working hard to safeguard their utility items. He won’t let anyone take away their hard-earned household goods. Fatik does not know what will be put into the fire. A few government-appointed people collect the crushed bamboo walls from the ghetto and add them to the flames. The more they burn, the more smoke rises. At a safe distance, a curious crowd observes the unfolding events.

Fatik packs goods in small quantities and takes them to Lali, who is resting under the shade. He quips, “I could have packed up sooner if I had someone to help. You’re in pain, huh? Hold on for a bit; we will board the train shortly.”

“Hey scoundrels, that’s mine. Keep it there, I’m telling you! Otherwise, I’ll put y’all in that fire.” Fatik rushes to their ruined house. It’s not a house anymore! An empty stretch reveals the impressions of bricks laid down for years. Fatik’s shanty looks the same — a square piece of land with torn plastic sheets and scattered, fragmented earthen roof tiles.

Lali continues to endure pain. Fatik appears exhausted; he is busy organising goods. There’s no point in disturbing him further with another complaint of discomfort. Lali remains silent and attempts to sketch the new place they will inhabit for the next few months or possibly years. No one will be a stranger there; they cannot afford the luxury of exploring exotic living. Fatik once told her, “Shashthida has affirmed that we can come back here once the air cools down.”

It’s easy to earn a living in the city, but finding a job is difficult in the countryside, where opportunities are scarce. Once the flyover is built, Fatik plans to return and set up a small eatery for the evenings. In a tone filled with love and care, Fatik tells Lali, “No one can resist the mutton curry you cook. All visitors will become regular customers at our shop.” Lali adds a touch of sass to her response, “I won’t. I’d rather teach you the recipe. You can then cook and feed them.” Gazing at the ceiling with wide eyes, Fatik remains lying in bed.

Lali does not believe in Fatik’s words that they will be able to come back here again. A few minutes ago, Hema came to see her, “My bad luck; I won’t get a chance to see your child. But you never know if I will meet you again somewhere else.”

“Won’t you come back here?” Lali asks.

“They will not allow us here again,” Hema replies. “The officials informed us that they were planning to build a marketplace below the flyover after its construction.”

Mum’s the word when Lali relays the news to Fatik. He murmurs, “But then Shashthida[1] has assured…”

“You can pursue a small shop in the proposed market,” Lali advises.

“I can’t say; they might ask for a cash lump sum as advance payment.” Fatik appears worried.

The pain shoots once again. Lali flings her legs aimlessly. The dusty floor reflects her movements. She remains silent. On the other side, Fatik gets into trouble with Dulu and his family. Dulu’s mother seems to have taken Lali’s rice pot. Lali raises her voice, “The pot is mine!” Unfortunately, her words go unheard.

2

Fatik knocks Lali with his bag, “Come on, the Hasnabad local is at platform eight. Walk along the straight direction.”

Lali has heard of the Sealdah railway station, but she has never been there. It is a large station with several platforms, numerous trains, and huge crowds. Passengers jostle against one another. With great caution, Fatik quickly walks across the platform to board the train and get into a compartment by any means necessary. There are likely a few travelling ticket examiners around, but during this time, they usually don’t enter the coach. Lali is unable to keep pace with Fatik and remains far behind him, but she compensates for the distance by tightly gripping one side of the gamcha[2] draped around his neck. Fatik collides with the commuters approaching from the other end, and a few passengers express their annoyance with a word or two of irritation. Fatik does not respond at all. Lali pulls her saree to cover her breast. She has no control over the saree girded around her head, which has now slipped onto her back.

The train will start in ten minutes. All coaches are full; not a single seat is vacant. Fatik quickly decides on a favourable compartment and boards the train with his wife. Lali cannot stand any longer, so she sits on the floor beside the door, her hands resting on her belly. Fatik arranges their bags around Lali. An elderly gentleman asks, “Where will you get off?”

“Barasat,” Fatik answers.

“What the hell are you doing here? Get inside the coach. Have you lost your mind or what? How can a sensible man board the train in such conditions?”

Fatik turns to his wife and whispers, “There aren’t any vacant seats. Do you still want to go inside?”

Lali refuses to move. The spasm has taken over her body and mind. She cannot stand up. She wants to stretch her legs to give her baby more space. However, the situation does not allow for that privilege. With each passing minute, more passengers crowd the coach, and the draft is cut off. In a dry voice, Lali calls out to her husband, “I cannot breathe. I need some air.”

“Wait a moment. The crowd should thin out after we pass two stations,” Fatik says.

As soon as the train departs, more than a handful of late passengers hurriedly board the coach. They will travel a long distance and want to get inside. The bags and goods piled around Lali create an obstacle to their movement. One of them raises his voice, “Is this a place to sit?” Another man from the crowd yells at Lali, “Stand up, I said!” Someone empathetically informs, “Try to understand; she is carrying.”

“Oh! This is horrible. Hey brother, you aren’t pregnant, are you? Better you stand up. More passengers will enter the coach at Bidhan Nagar and Dum Dum. They will smash you to death.”

Fatik gets anxious and follows the instructions. Lali shrinks in fear, feeling breathless. In her womb, she carries their only child, who waits to see the world — as if the baby complains, “I cannot stay in this small dark space anymore, Ma!” The passengers become frightened as Lali lets out a low moan of pain.

Fatik bends toward Lali as much as possible to ask, “I’m sure it’s terrible to bear any longer.”

“No air; it’s suffocating!” Lali sounds fragile.

“It won’t be long; I’ll take you to the hospital as soon as we reach there. Shashthida has shared the address.”

Lali’s facial muscles contort in extreme agony. Fatik isn’t sure whether she has heard him. Intoxicated, Fatik had seen her suffer from pain before; during those times, he did not feel her distress. Lali wept profusely. Fatik never intended to hurt her but lost control as he downed liquor. The very next day, Fatik committed to his wife, saying, “I won’t trouble you anymore. All I want is a son!”

With a hint of dejection in her eyes, Lali poked, “Right! So, he can run a liquor shop you longed for.”

“Shut up! I’ll make him a real gentleman,” Fatik readily addressed her concern.

3

Several travellers board the train as soon as it stops at the next stations. Lali, who somehow remains seated on the floor, gets pressed painfully against the legs. She feels worse than ever. Fatik seems restless and cautiously peeks out from behind the crowd to read the station names. At times, he turns to look at the goods around him. A few passengers become irritated, saying, “What’s wrong with you? Why don’t you stand still?”

“Be careful, dada! Take care of your pocket. You never know…Dasbabu lost three hundred bucks yesterday only.” Someone from the crowd airs the words of caution.

Fatik understands the meaning of such lines. He does not utter a word, for he knows if he begins an argument, they will forcibly push him out of the coach at the next station and beat him like hell. He requests the passenger beside him, “Dada, please let me know as we reach Barasat.”

“We are currently at Cantonment. Please be patient; it will take another thirty minutes or so to reach Barasat.”

4

Lali wants to scream. She feels thirsty. Amid the numerous legs visible to her, she cannot identify Fatik’s. Even when Lali looks up to see the faces, she is unable to locate her husband. The child in her womb revolts; it will not tolerate the torture to which the mother is subjected. The baby twirls, rapidly changing positions. Lali realises that her child is responding to the world — specifically, the passengers in the coach. The tiny tot wishes to emerge from confinement to greet them. Lali is afraid — will they treat the child as lovingly as their family?

Fatik bends down and says, “We will get off at the next station. Several others will disembark. I’ll first grab the bags, and then I’ll help you off the coach. Be careful.”

Lali gathers her courage and prepares for the exit. She moves her palm over her belly, saying, “A little more waiting, Baba[3]!”

The train halts at Barasat. Passengers disembark from the train like a vigorous flow of water. Fatik feels puzzled as the bags scatter. A few passengers are still getting off. Meanwhile, many commuters waiting to board the train begin to enter. Ignoring the chaos, Lali tries to stand but fails. Fatik quickly gathers their bags and helps them to ensure a swift exit. The passengers ready to disembark push him out of the coach. Fatik cannot withstand the force and is shoved away from the train. The coach has room for more passengers and fills up quickly. Lali crouches toward the gate and cries, “Help! I’ll get off; stop the train.” People leaning out of the coach warn her.

No one can hear Lali. Fatik rushes to the coach to grip the gate’s rod, but he fails every time he stretches his hand to grasp it. A guy leaning out of the coach holds it in such a way that Fatik cannot access the rod. He refuses to give up and keeps running alongside the train. The thick crowd challenges his swift movement. Amid several passengers inside the coach, Fatik sees his wife’s hands and the two pairs of bangles she wears. He reaches the far end of the platform.

Fatik breathes rapidly. He is exhausted and sweating profusely. He shivers while keeping his head lowered. A drop of sweat rolls down his forehead and falls onto the tip of his nose. Fatik can see the passengers hanging out of the coach, trying their best to get inside. Amid their relentless efforts, Lali’s hands disappear.

[1] Dada/Da: In Bengali, the elder/older brother is calledDada(Dain short).Dada or Daissuffixed to the first or last name when addressing an acquaintance, relative, or stranger during a conversation. Bengalis also suffix Babu to a name (first or last) to show respect.

[2] A traditional, thin cotton cloth (generally, a handloom product) of varyinglengths used in Bengali households to dry the body after bathing or wiping sweat. It is also used in several Hindu rituals.

[3] Baba is father. But parents often use this word affectionately to address their sons.

(Translated from the original Bengali by Kiriti Sengupta. First published in the EKL Review in December 2021)

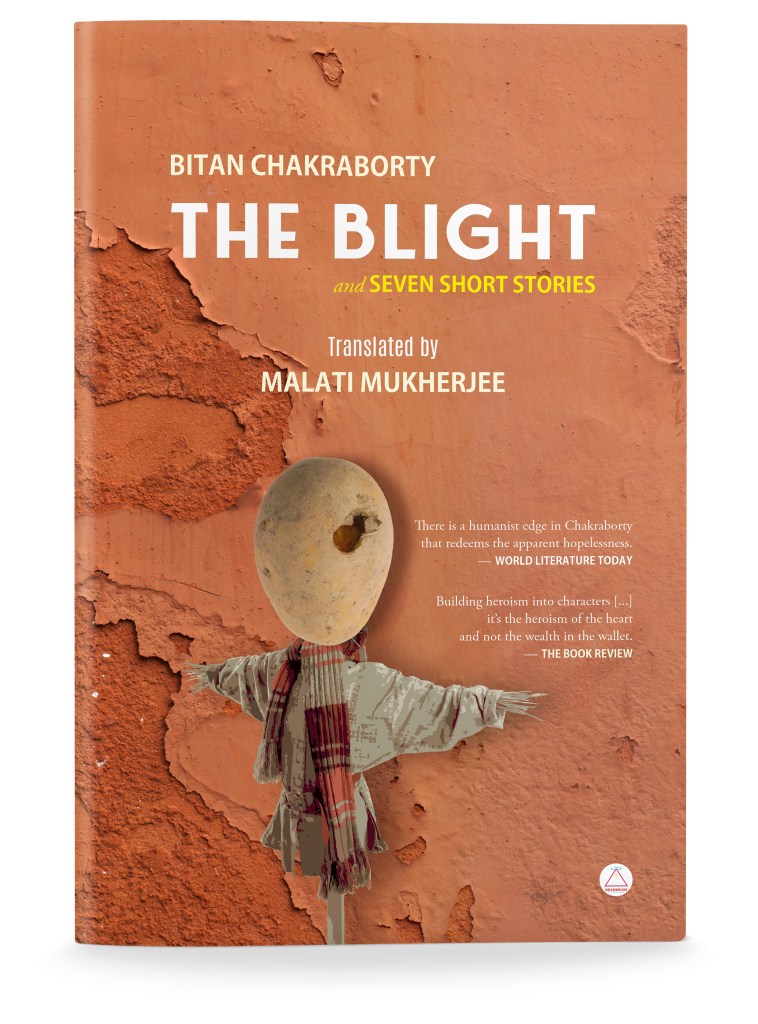

Bitan Chakraborty is essentially a storyteller. He has authored seven books of fiction and prose, translated two collections of poems, and edited a volume of essays. Bitan has received much critical acclaim in India and overseas. Bougainvillea and Other Stories, The Mark, Redundant and The Blight and Seven Short Stories are four full-length collections of his fiction that have been translated into English. He is considered one of the flag-bearers of Indian poetry in English, being the founder of Hawakal Publishers. When Bitan isn’t writing or editing, he is photographing around Rishikesh, Varanasi, Santiniketan, among other places. He has successfully participated in the 3-day-long Master Class on Photography led by the legendary Raghu Rai. Chakraborty lives in New Delhi with Jahan, a pet Beagle. More at

www.bitanchakraborty.com.

Kiriti Sengupta has had his poetry featured in various publications, including The Common, The Florida Review Online, Headway Quarterly, The Lake, Amethyst Review, Dreich, Otoliths, Outlook, and Madras Courier. He has authored fourteen books of poetry and prose, published two translation volumes, and edited nine anthologies. Sengupta serves as the chief editor of Ethos Literary Journal and leads the English division at Hawakal Publishers Private Limited, one of the top independent presses established by Bitan Chakraborty. He resides in New Delhi. Further information is available at www.kiritisengupta.com.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International