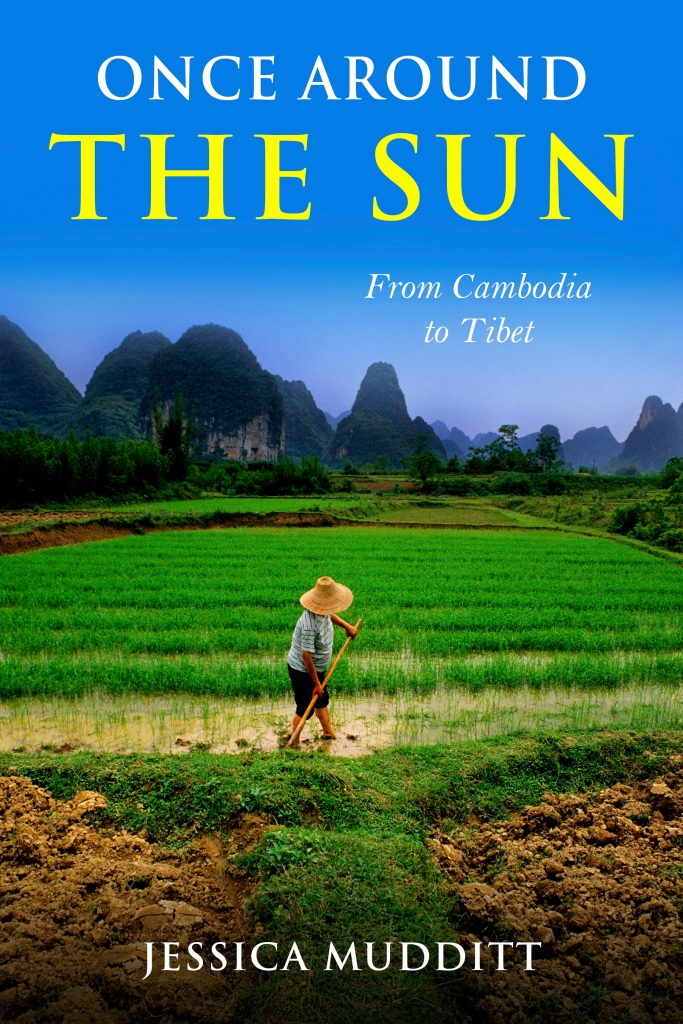

Title: Once Around the Sun: From Cambodia to Tibet

Author: Jessica Mudditt

Chapter 20 – In or out?

As I walked the streets of downtown Hohhot in search of a travel agency, I felt further than five hundred kilometres from Beijing. I was still in East Asia, but the capital city of Inner Mongolia had Central Asian influences too, such as the cumin seed flatbread I bought from a hawker with ruddy cheeks and a fur hat. I passed a Muslim restaurant with Arabic lettering on the front of its yellow-and-green facade, and many street signs and shops featured Mongolian script as well as Mandarin. With its loops, twirls and thick flourishes, Mongolian looked more similar to Arabic than Chinese. In actual fact, the top-down script is an adaptation of classical Uyghur, which is spoken in an area not far to the west.

The winds that blew in from the Russian border to the northeast were icy cold, so I was glad to soon be inside a travel agency. It was crammed with boxes of brochures and a thick film of dust covered the windowpanes. Hohhot is the main jumping-off point for tours of the grasslands, so I was able to get a ticket for a two-day tour that began the following morning.

I wasn’t enthusiastic about going on a tour because I preferred to move at my own pace, however there was no other way to access the grasslands. The upside was that I was guaranteed to sleep inside a ger, which is a circular tent insulated with felts. The Russian term of ‘yurt’ is better known. I had read that Inner Mongolia was a bit of a tourist trap for mainland Chinese tourists, but I was nonetheless excited to get a glimpse of the Land of the Weeping Camel.

I walked into a noodle shop and a customer almost dropped her chopsticks when she saw me. The girls at the cash register were giggling and covering their faces as I pointed at a flat noodle soup on a laminated menu affixed to the counter.

Foreign tourists must be thin on the ground in Hohhot, I thought as I carried my bowl over to a little table by the window.

Inner Mongolia was one of the few places that Lonely Planet almost discouraged people from visiting: ‘Just how much you can see of the Mongolian way of life in China is dubious.’ But I was still keen to see what I could.

I ate slowly, enjoying each fatty morsel of mutton. I was pretty good with chopsticks by that point – I’d never be a natural, but I didn’t drop any bits of mutton into the soup with a splash, as I used to in Vietnam.

Hohhot seemed a scruffy, rather bleak sort of city – or at least in the area where I was staying close to the train station. Street vendors stood cheek by jowl on one side of the road, calling out the prices of their wares. The opposite side was under construction and the one still in use was unpaved, which meant that two lanes of traffic had to navigate a narrow area of bumpy stones while avoiding massive potholes and piles of dirt. I saw a motorbike and a three-wheel truck almost collide.

I spent the next few hours wandering around the Inner Mongolia Museum, which has a staggering collection of 44,000 items. Some of the best fossils in the world have been discovered in Inner Mongolia because its frozen tundra preserves them so effectively. The standout exhibit for me was the mammoth. It had been discovered in a coal mine in 1984 and most of its skeleton was the original bones rather than replicas. I gazed up at the enormous creature and tried to imagine it roaming the earth over a million years ago. Mind-boggling.

I admired the black-and-white portraits of Mongolian tribesmen, and then took photos of a big bronze statue of Genghis Khan astride his galloping mount. The founding leader of the Mongol Empire was the arch-nemesis of China, and parts of the Great Wall had been built with the express purpose of keeping out his marauding armies. Genghis Khan must have rolled in his grave when China seized control of a large swathe of his territory in 1947.

What was once Mongolia proper became a Chinese province known as ‘Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region’. This long-winded name is an example of Orwellian double-speak. So-called ‘Inner Mongolia’ is part of China, whereas the independent country to the north is by inference ‘Outer Mongolia’. Nor is the Chinese region autonomous. The Chinese state has forced Mongolians to assimilate. Their nomadic lifestyle and Buddhist beliefs had been pretty much eradicated, and although speaking Mongolian wasn’t outlawed, learning the state language of Mandarin was non-negotiable.

On top of this, the government provided tax breaks and other financial incentives to China’s majority ethnic group, the Han Chinese, if they relocated to Inner Mongolia. Mongolians now account for just one in five people among a total population of 24 million. The same policies of ethnic ‘dilution’ exist in China’s four other ‘autonomous regions’, which include Tibet and Xinjiang, the home of the Uyghurs.

Shortly before I left the museum, I came to a plaque that described the official version of history, which was at odds with everything I’d read in my Lonely Planet.

‘Since the founding of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region fifty years ago, a great change has happened on the grasslands, which is both a great victory of the minority policy and the result of the splendid leadership of the Communist Party of China. The people of all nationalities on the grassland will never forget the kind-hearted concerns of the revolutionary leaders of both the old and new generations.’

I rolled my eyes, snapped a photo of the plaque for posterity, and continued walking.

* * *

I didn’t venture far from my hotel for dinner because I planned on having an early night. I chose a bustling restaurant with lots of families inside and was waiting for a waiter to come and start trying to guess my order when a group of men at the next table caught my eye. They seemed to be waving me over.

Me? I asked by pointing at myself.

Yes, they were nodding. Shi de.

I happily joined the group and introduced myself by saying that I was from ‘Aodàlìyǎ’. I think they were Han Chinese, as they didn’t look Mongolian. I whipped out my phrasebook and tried to say I had come from Beijing, but I was fairly certain they didn’t understand me.

Anyhow, no matter. Ten shot glasses were filled from a huge bottle of baijiu, and I was soon laughing as if I was with old friends. One of the slightly older guys used a set of tongs to place wafer-thin slices of fatty pork into the bubbling hotpot on the table, followed by shiitake mushrooms and leafy greens. As the impromptu guest of honour, my bowl was filled first once it was cooked – by which time I’d already had three shots.

The hotpot was fantastic, and I had to remind myself not to finish everything in my bowl. Bethan had told me that Chinese etiquette requires a small amount of food not to be eaten at each meal. This indicates that it was so satisfying that it wasn’t necessary to eat every last bite. As a kid, it was ingrained in me to finish everything on my plate. I loved food and was generally in the habit of licking my bowl clean, so I had to exercise a certain amount of restraint.

I had just rested my chopsticks across the top of my bowl to signal I was finished when I was invited to go sit on the wives’ table, which was across from the men’s. The women were very sweet and a couple of them seemed to be around my age. I once again tried to communicate using my phrasebook, but I was hopelessly drunk by then. I could hardly string a sentence together in English, let alone Mandarin. I was also beginning to feel queasy from the baijiu, so I gratefully accepted a cup of green tea from the porcelain teapot that came my way on the lazy Susan. After taking some photos together, I bid the two groups ‘zaijian’ (goodnight). I tried to contribute some yuan for the meal, but they wouldn’t hear of it. I curtsied as a stupid sort of thank-you, and then I was on my way.

* * *

More hard liquor awaited me the following day. A striking woman in a red brocade gown with long sleeves handed me a small glass of baijiu as I stepped off the minibus a bit before noon.

‘It’s a tradition,’ she said with a smile, while holding a tray full of shots.

I downed the baijiu with my backpack on and grinned as the backpacker behind me did the same. There were four foreign tourists on the tour, and about eight domestic ones. The liquor gave me an instant buzz, which I needed. I hadn’t slept well and woke up feeling lousy, so I’d kept to myself during the two-hour journey. Even though I should have been excited, I got grumpier and grumpier as the reality of being on a tour began to sink in. Plus, the landscape was not the verdant green steppes I’d been expecting. At this time of year, it was bone dry and dusty. It hadn’t occurred to me to check whether my visit coincided with the low season.

I began chatting to the other tourists. The guy who had the baijiu after me was Lars from Holland. There was also a couple from Germany. I could immediately tell they were pretty straitlaced. Their clothes looked very clean and functional, and the girl refused the baijiu.

The woman in red introduced herself as Li, our tour guide. Then she led us along a path lined with spinifex to a dozen gers. They faced each other in a circle, and off to the right was a much larger ger with the evil eye painted on its roof and Tibetan prayer flags fluttering in the fierce winds. There were no other buildings in sight and no trees.

Li told us to meet inside the big ger in fifteen minutes after we’d put our stuff in the smaller gers she proceeded to assign us. Lars and I would be spending the night in a ger with ‘82’ painted on its rusted red door. There certainly weren’t eighty gers, so the logic behind the numbering system wasn’t clear – but no matter. The German couple took the ger to the right of ours.

These were not portable tents for nomads. Each ger was mounted on a concrete base and I think the actual structure was made of concrete too, and merely wrapped in grey tarpaulins. The door was made of metal and at the top was a sort of chimney structure – perhaps for ventilation. Like igloos, the only opening was the door, and it was pitch-black inside. I located a dangling light switch as I entered.

‘Ah – I love it!’ I exclaimed.

It was a simple set-up, with single beds lining the perimeter and a low table in the middle of the room. Patterned sheets were draped from the concave ceiling. I chose the bed with a framed portrait of Genghis Khan above it. Lars put his backpack next to a bed on the other side. I was happy enough to share a ger with him. He gave off zero sleazy vibes.

‘I might just take a couple of those extra blankets,’ I said to Lars as I piled on a few extra floral quilts from another bed. The wind had an extra iciness to it out on the steppes and I shuddered to think what the temperature would drop to overnight. We zipped our jackets back up and headed out.

I wandered over to the toilet block, which was quite a distance from the gers. I made a mental note to drink as little as possible before getting into bed to avoid having to go in the night. Once I got closer to the toilets, I was glad they were so far away. The stench was unbelievable.

In the female section were two concrete stalls without doors. In the middle of the floor in each was a rectangular gap. I almost gagged. Just a few centimetres away from the concrete was an enormous pile of shit. I could make out bits of used toilet paper and sanitary pads and there were loads of flies buzzing around. Without running water or pipes, the excrement just sat there, day after day, building up. I would have turned and walked straight back out but I was busting for a wee. I held my breath so I wasn’t inhaling the smells. I wanted to close my eyes too, but I was terrified of falling in, so I had to look at what I was doing. I couldn’t get out of there fast enough.

‘Oh my god, Lars – the drop toilets are totally disgusting,’ I said after I met up with him in the big ger. ‘It’s just a pit of shit without running water.’

‘I know an American girl who fell into a drop toilet in China last year,’ he said.

‘No way,’ I said with a shudder.

‘Yeah. She said it was terrible. She was in a really poor village somewhere in central China and she went to the toilet at night. She couldn’t see that some of the wooden planks had gaps in them – and then one of them broke and she fell in. She was up to her neck in shit. She was screaming for people to come help her. Apparently, it took them half an hour to fish her out, and all the while she could feel creatures writhing around her body. She cut her trip short and had to get counselling when she got home.’

‘I bet she did,’ I said. ‘That’s the most disgusting thing I’ve ever heard in my life. The poor girl.’

Just then Li appeared and said we were heading outside to watch horse racing and traditional wrestling after some sweet biscuits and tea. We assembled around a fenced area where there were about thirty ponies tethered to poles. Some were lying down while still saddled.

‘Horses usually sleep while standing up, so these ponies must be knackered – pardon the pun,’ I joked to Lars.

Notwithstanding, they looked to be in reasonably good condition, with shiny coats and no protruding ribs. There were chestnuts, bays and dapple greys.

I heard the sound of hoofbeats and looked behind me. A group of men on horseback came thundering across the steppes. It was a magnificent sight, and any lingering resentment I had about being on a tour melted away.

One of the men rode ahead of the rest. He was wearing a cobalt-blue brocaded tunic and his wavy black hair came down past his ears. He was really good-looking. He approached Li with a smile, said something to her and dismounted with the ease of someone who had probably started riding horses before he learned to walk. Li and the man exchanged a few words – I definitely saw her blush – and then he got back on.

‘Gah!’ he yelled as he dug his heels into his horse’s sides.

The other horsemen followed after him with whoops, leaving a trail of dust in their wake. These Mongolian ponies were only about twelve or thirteen hands, but they sure were fast and could turn on a dime. I loved watching them carve up the dry earth.

Next a group of men on motorcycles appeared along the track. There were quite a lot of them – at least twenty. We formed a big circle, and the traditional wrestling began. I wasn’t sure what the rules were, but it was fairly self-explanatory: one man got another in a headlock and thumped him to the ground. The next man came along and fought the winner, and so on and so forth. The spectators egged on the fighters with what I assumed were good natured cat calls. Everyone was grinning. By the time the wrestling matches were over, the fighters were absolutely covered in dust and the sun was beginning to set. I’m sure it was all staged for our benefit, but it was good fun.

With the seamless orchestration of a tour that has been done a thousand times before, we gravitated to the big ger. Dinner was bubbling away in a large clay pot and it smelled pretty good. There was also a big vat of noodles with black sauce and the ubiquitous Chinese vegetables of thinly sliced carrot, bok choy, baby corn and onion. There was a bottle of baijiu on each table.

We were serenaded with traditional music while we ate. One of the instruments reminded me of the didgeridoo and there was also a violin. I had read that strands of horse mane are used to make violin strings. The male singer had a deep voice that was almost a warble, and it was hauntingly beautiful.

Five men and women emerged from behind a red curtain and began to dance. They wore long-sleeved, billowing satin tunics that were cinched at the waist with embroidered belts. One of the women had a tall hat made of white beads that dangled down to her waist. It must have been heavy. It was a high-energy display of kicks and splits and parts of it were reminiscent of Irish dancing. They twirled their billowing skirts like sufis. The Chinese tourists started clapping in time with the music and then we all joined in. Sure, it was a bit cheesy, but I was really enjoying myself. At the end of the concert, we had photos with the performers as they were still trying to catch their breath.

We were given torches to light our way back to our gers. It was absolutely freezing, so I wore all my clothes to bed. I snuggled into my blankets and pulled them right up to my chin, feeling grateful for the warmth of Bethan’s jumper.

Mercifully, I slept right through until morning and avoided a late-night visit to the shit pit.

When I wandered out of the ger the next morning, breakfast was being prepared nearby. The carcass of a freshly slaughtered sheep was hanging from the back of a trailer. A man was skinning it while the blood drained out of its neck into a big metal bowl. Its head was in a second bowl, while squares of wool were laid out flat to dry on a tarp. A toddler in a puffy orange jacket was playing in the dust while his mother worked away at skinning parts of the wool. What distressed me more than butchery up close was the live sheep that was watching on from the back of the trailer. He presumably knew he was next.

After a breakfast of ‘sheep stomach stew with assorted tendons’ (as Li described it) we headed out for a ride on the steppes. I couldn’t wait to ride a horse again. I’d spent most of my childhood obsessed with horses, and I was lucky enough to have one for a few years, until I got older and became more interested in hockey and parties.

I rode a stocky bay with a trimmed mane that bobbed up and down as it trotted along the path. I looked over its perky little ears. The saddle had an uncomfortable pommel that kept jabbing me in the stomach, but I loved being under the wide open sky. It was a pale blue with just a few wispy clouds. Sheep grazed and crows rested on clumps of rocky outcrops.

I winced at the Chinese guy ahead of me, who was bouncing out of time to the rhythm of his horse’s gait and landing with a heavy bump in the saddle; his oversized suit flapping in the wind and his feet poking out straight in the stirrups. Much easier on the eye was the guide two horses ahead of him. He was every inch the Mongolian cowboy. Dressed from head to toe in black, he wore a leather jacket, cowboy hat and scuffed black cowboy boots. He never took off his wraparound sunglasses and he spoke little. He smouldered like the heartthrob actor, Patrick Swayze.

We’d travelled several kilometres when we came to a building block that was the same greyish brown as the earth. Inside it had a cottage feel. We sat around a table covered with a frilly tablecloth and drank yak milk. As we did, Lars told me about his day trip to North Korea. While in South Korea for a couple of weeks, he had visited the demilitarised zone (better known as the ‘DMZ’), where a ceasefire was negotiated between the two Koreas in 1953. In a military building is what is known as the ‘demarcation line’ – and Lars had one foot in North Korea and another in South Korea. I hung on his every word.

Our conversation got me thinking about how cool it would be to go to North Korea. I was actually quite close to the border. When I got back to the ger, I retrieved my Lonely Planet out of my bag and thumbed to the section titled ‘Getting there and away’, which had instructions for every country that borders China.

‘Visas are difficult to arrange to North Korea and at the time of writing, it was virtually impossible for US and South Korean citizens. Those interested in travelling to North Korea from Beijing should get in touch with Koryo Tours, who can get you there (and back).’

I was pretty sure the cost would be prohibitive for my budget and decided to stick with my existing plan of cutting south-west towards Tibet. Maybe one day I’d get the chance to visit North Korea, but it wouldn’t be on this trip.

Once back in Hohhot, I boarded a train bound for Pingyao. As I watched the apartment blocks pass by in a blur, I thought with satisfaction about the past twenty-four hours. Any visit to Inner Mongolia is problematic, but I couldn’t fault the Chinese tour company. They had made every effort to keep us entertained. Mongolian culture was so new to me that I couldn’t even tell whether something was authentic or staged, but I had seen and done all the things I hoped to during my visit. And, sure, my time there was really brief. But I’d be forever grateful to have seen a part of the world I thought I’d only ever get to see in a documentary.

About the Book: While nursing a broken heart at the age of 25, Jessica Mudditt sets off from Melbourne for a year of solo backpacking through Asia. Her willingness to try almost anything quickly lands her in a scrape in Cambodia. With the nation’s tragic history continuing to play out in the form of widespread poverty, Jessica looks for ways to make a positive impact. She crosses overland into a remote part of Laos, where friendships form fast and jungle adventures await.

Vietnam is an intoxicating sensory overload, and the hedonism of the backpacking scene reaches new heights. Jessica is awed by the scale and beauty of China, but she has underestimated the language barrier and begins her time there feeling lost and lonely. In circumstances that take her by surprise, Jessica finds herself hiking to Mount Everest base camp in Tibet.

From a monks’ dormitory in Laos to the steppes of Inner Mongolia, join Jessica as she travels thousands of kilometres across some of the most beautiful and fascinating parts of the planet.

About the Author: Jessica Mudditt was born in Melbourne, Australia, and currently lives in Sydney. She spent ten years working as a journalist in London, Bangladesh and Myanmar, before returning home in 2016. Her articles have been published by Forbes, BBC, GQ and Marie Claire, among others. Once Around the Sun: From Cambodia to Tibet is a prequel to her earlier book, Our Home in Myanmar.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International