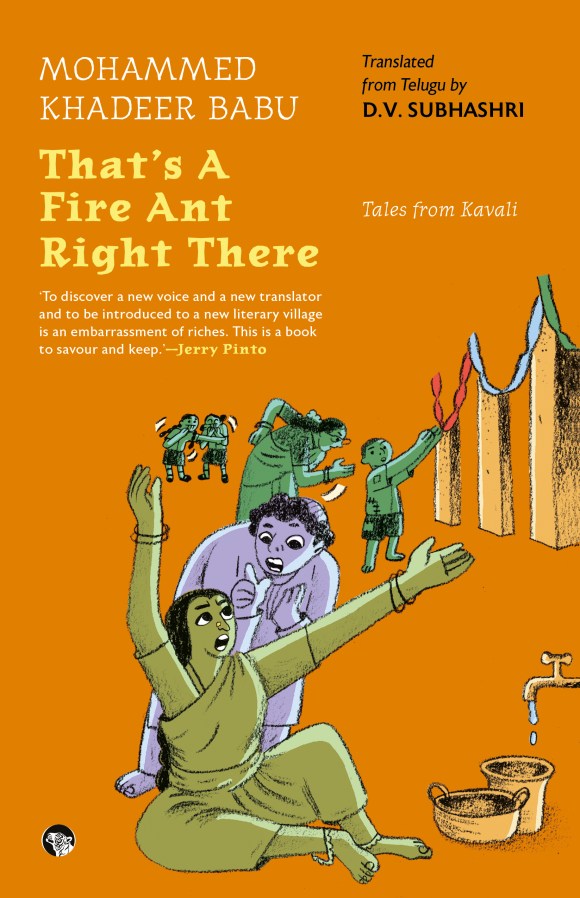

Title: That’s A Fire Ant Right There! Tales from Kavali

Author: Mohammed Khadeer Babu

Translator: D.V. Subhashri

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

True-blue Palavenkareddy!

It’s only now when he’s running a Palav Center in front of Kavali Court that he’s able to see twenty-six rupees in his hand for every plate he sells, but there was a time in our childhood when Palavenkareddy too was down on his luck!

Palavenkareddy (Palav + Venkareddy) was my father’s best friend. He was also the one who got him married.

When my grandfather Mastan Sayibu was considering giving my mother’s hand in marriage to my father, it seems he went straight to Palavenkareddy to enquire about my father’s ‘conduct’.

‘Don’t worry about that boy, saami! He’s 24-carat gold. You can get them hitched with your eyes shut!’ Palavenkareddy reassured my grandpa and lifted a load off his mind.

Although seven-eight years older than my father, Palavenkareddy, always dressed in white, appeared much younger, with his toned muscles (he was a wrestler once, I might add), shining skin and dyed hair.

At the time of nikah, as my mother was still a young fourteen-year-old, Palavenkareddy used to address her as ‘ammayi’ or ‘girl’, and continued to call her that even after marriage. Whatever his feelings for my father, he definitely favoured my mother and had more affection for her.

If Sankranti was here, Palavenkareddy wouldn’t be far behind. He’d show up with a large steel carrier full of ariselu, manuboolu, laddulu and hand it to my mother saying, ‘Here you go, girl.’ Then he would take my father, my brother and me to his house, fill our leaf-plates full of sweet payasam and treat us to a full festival meal. (This is also the time to reveal yet another truth. Until recently, whenever my mother had to go to a wedding or any other function, she would borrow Palavenkareddy’s wife’s or daughter-in-law’s jewellery as if she had every right to do so.)

I don’t really know if he was into farming or not, but as kids we always saw she-buffaloes tied up at their house. His wife would wake up early and toil hard, tending to the buffaloes all day. Seemingly in an effort to reduce her drudgery, he dabbled in various businesses, but being a man of truth, failed to make money in any of them. Finally, he hit the jackpot when he opened the Palav Centre. And since then, his surname changed from Remala to Palav and he came to be known as Palavenkareddy to everyone in our town.

During our childhood, he owned a cloth store near the Ongole bus stand. Barely a metre would sell each day at the shop, but Palavenkareddy and his elder son could always be seen dutifully minding the store.

Now why I’ve been telling you this long story about Palavenkareddy is because when the month of Ramzan arrived we were forced to draw on his services—thanks to my mother’s pestering.

‘All the ladies in the street are going to Gademsetty Subbarao’s shop and getting themselves whatever clothes they want. Why don’t you also toss me a hundred or two? I’ll go get the children some new clothes.’ My mother had been badgering my father ever since Ramzan had begun.

My father responded with neither ‘aan’ nor ‘oon’. Ultimately, she decided that this was not the medicine for my father’s attitude and cleverly started instigating my grandma.

‘Rey abbaya! How heartless can you get! Even if we adults don’t buy anything, how can you not get a few pieces of cloth for the children? When other children in the street roam around wearing new clothes, won’t ours feel bad?’ poked my grandma.

Who knows what came over him, but he replied, ‘Send the older one and the second one to the shop in the evening. If I happen to get money by then, I’ll buy them some, alright,’ and left for work.

When evening came, with high hopes my mother dressed us up—not just me and my brother but also our sister—and sent us to our electrical shop on Railway Road.

And my father? What did he do? When we reached there, he was sitting at the table with a deadpan face and hands over his head. The moment he saw us, he stood up and said, ‘Not today. Go home,’ then picked up my little sister and prepared to lock the shop.

We were crestfallen. My brother was on the verge of tears.

That is exactly when, like Gods appearing out of nowhere, Palavenkareddy appeared before us. On seeing us, he laughed, ‘Endayyo? What’s up here? All the little Nawabs have descended together.’

My father too laughed and told him the matter. ‘What, Karim Sayiba? The children have come for their festival clothes and you’re taking them back empty-handed? Didn’t you think of my shop? Come, come, let’s go,’ Palavenkareddy urged him.

‘Not now, Enkareddy. We’ll see when I have the money,’ said my father reluctantly.

‘Do you ask for money when you do electric work in my house? Then why would I demand money for the children’s clothes?’ he insisted, herding us along. And so, together we all went to Palavenkareddy’s cloth shop near Ongole bus stand.

‘Karim Sayiba! It’s not as if you’re going to buy clothes again anytime soon, so might as well pick a sturdy fabric that will last a few days,’ he said, opening a wooden almirah and pulling out a tough-looking piece of blue cloth from the swathes of fabric inside.

‘Guarantee cloth. No question of tearing at all,’ he said.

Whenever my father hears the word ‘guarantee’, he forgets everything else and says, ‘Yes, give that one’, and so, he said the same to Palavenkareddy as well.

That was that! Before we knew it, in five minutes Palavenkareddy had cut the cloth and all of us had given our measurements to the tailor Sayibu beside the shop, who promptly soaked the cloth in an iron bucket.

(Excerpted from That’s A Fire Ant Right There! Tales from Kavali by Mohammed Khadeer Babu, translated by D.V. Subhashri. Published by Speaking Tiger Books)

ABOUT THE BOOK: Captured in the innocent voice of a young boy, Mohammed Khadeer Babu’s Chaplinesque-style of portraying misery through humour shines a sweeping light on Muslim lives in coastal Andhra. Populated with strong women, cheeky scamps, virtuous dawdlers and scrupulous teachers, his witty storytelling in the Nellore dialect is a riveting portrayal of the daily struggles of adapting to a majoritarian world in small-town India. Belying the nostalgic memories of childhood are scathing observations of the education system, child labour, social barriers, and casteist attitudes. Yet, the stories also resound with a clear message of friendship, especially among Hindus and Muslims, making this book essential reading in today’s fraught times, to remind ourselves of our inherited legacy of communal harmony—which makes it possible for the young narrator to say, ‘I’ve never regretted even once that I didn’t learn Urdu or that I don’t know Arabic, or that I have never even touched the Quran in these languages, only in Telugu.’

D.V. Subhashri’s unique translation, which retains all the richness of the original, quaint expressions and sounds et al, brings a smile to our faces, while showing us why the book made Khadeer Babu a household name in the Telugu community. This first English translation of his work opens up a new world for us.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Mohammed Khadeer Babu is a senior journalist and award-winning writer in Telugu with short stories, anthologies, non-fiction books and movies to his credit. A two-time Katha awardee, his stories have won various prizes at the state and national level and earned him the Government of Andhra Pradesh Achievement Award in 2023.

ABOUT THE TRANSLATOR: D.V. Subhashri is a multilingual writer and translator based out of Bangalore. Her stories and translations have appeared in various online magazines and her children’s books have won awards in Telugu and English. She is currently translating two books from Telugu and Kannada.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL