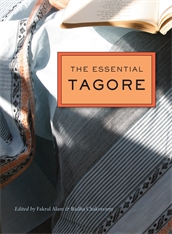

Anasuya Bhar explores the history of the National Anthem of India, composed by Tagore in Bengali and translated only by the poet himself and by Aruna Chakravarti. Both the translations are featured here.

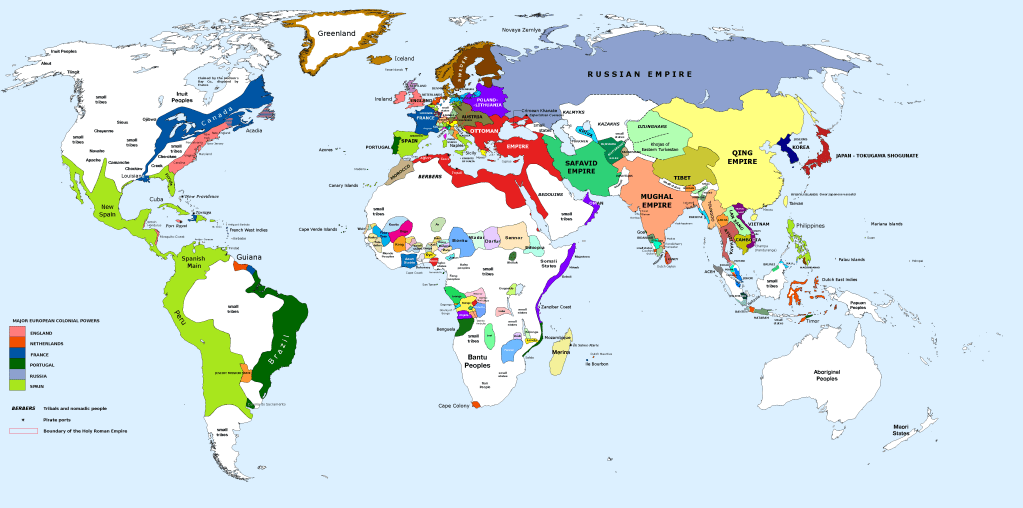

The national anthem and the national song of India are both parts of a post-colonial narrative and did not originate prior to the British colonisation of the country, which happened effectively, from the middle of the eighteenth century. India has been broadly classified as a civilisation and a cultural phenomenon, rather than a race or a territorial presence prior to the British colonisation.

India has remained an idea ever since the ancient times, perhaps even prior to the advent of the Classical Graeco-Roman civilisation of the west. The historicisation of India’s past has been a much debatable issue, with European historians representing India from their perspective. Much damage was done, for instance, by James Mill’s The History of British India (1817), which rubbished the country as thoroughly debased and wanting the civilisational touch of the European west. The reality of India, or more correctly Bharat, inhered in the local and regional historical specificities, its literature, culture, myths and legends. The historical perspective of our inhabitants was that of the Puranic history whose chronology, order and narrativity depended on a time scale different from the idea of time in the western rationale for chronology. In other words, the European west’s rationale consequent of the enlightenment, and the enlightened concept of history, was a later addition to the Indian consciousness.

The concept of a distinct nation, and as an individual entity in the consciousness of a socio-political presence in the history of the world, was also, a comparatively belated concept in our country. In fact, it was not earlier than the Mughals that the country was conceptualised as a unified entity from the North to the South, from the East to the West. The Indian sub-continent is strategically guarded by the geographical presence of the Himalayan range, the Indian ocean, the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea. Hence, the territorial boundaries which become crucial in determining the political borders of the European or the American west are not of much consequence over here. The borders that are present in the former continents are a result of political aggression and imperialism. The borders that ensued in the Indian subcontinent and eventually created Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Burma, Bangladesh and also Sri Lanka, are, however, a result of the European and, particularly, British intervention.

The consciousness of India’s nationalism was, as mentioned in the beginning, a later one and quite clearly a colonial aftermath. Among the first to mention the lack of an indigenous history was Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay (1838 – 94), the celebrated novelist and intellectual of nineteenth century Bengal, who himself attempted to write, through his various essays, a historical consciousness for his country. The writer of our national song ‘Bande Mataram’ (in Anandamath, 1882), Bankimchandra was also the first to think of a ‘jatiyo’ or a nationalist consciousness, and attempted to take a fresh look at the puranic history based on myths and legends. He rewrote the narrative of Krishna, and also looked afresh at the fundamentals of the Hindu religion.

The nationalist consciousness was given a fresh lease through the several attempts for promoting indigenous products and enterprises by the Tagores of Jorasanko in Kolkata. The Hindu Mela (Hindu fair), begun since the mid-1860s by Dwijendranath Tagore (1840 – 1926) was among the first to strike concepts of an indigenous nationhood, by giving impetus through homespun fabrics, cultivation of rural handicrafts and traditional food items like pickles or ‘bori’, such that a space could be created independent of the parameters used by the colonial masters. Rabindranath (1861 – 1941) also refers to several attempts of his elder brother Jyotirindranath (1849 – 1925), in creating the matchstick factory or even striking a competition in the ship trade with their English counterparts in the waters of Bengal in his autobiographical Jibansmriti (My Reminiscences, 1911). He also mentions the latter’s attempt at designing a national dress for the country, trying to fuse various drapes of traditional clothing. This is again very interesting because, a distinctive sartorial appearance would help in identifying the Indian from the European, even externally. The sari as we wear it now, was first conceptualised by Jnanadanandini Devi (1850 – 1941) of the Tagore household. She gave the Indian women a dignified attire by fusing the styles of Parsis and Gujaratis, and also by improvising on the styles of the European gown to give us the blouse-jacket. The unification of various styles automatically veered towards a oneness in the same territorial boundaries and the nationalistic consciousness came first through cultural means.

The Tagores of Bengal were also among the first, after Rammohan Roy (1772 – 1833), to venture beyond their homes. Dwarakanath (1794 -1846), grandfather of Rabindranath, not only stayed in England for a substantial period of time, but also endeared himself to Queen Victoria as the ‘Prince’. Debendranath (1817 – 1905), his son, was in the habit of touring the Himalayas extensively, and even took his youngest son Rabi along with him. Satyendranath (1842 – 1923), another of his sons, was the first Indian to qualify in the Indian Civil Service; he too, extensively toured several parts of India and abroad. Rabindranath was a frequent traveller from a very early age. The women of the Tagore household, beginning with Jnanadanandini Devi also moved out of their antarmahal (inner quarters) and into the other parts of their country and even the world. Indira, Mrinalini, Sarala, Pratima along with Jnanada were frequent travellers both within and outside the country. Hence, the country and the ideology of India as a nation were familiar concepts to the members of this remarkable family from Bengal. Of course, there were other influential households in nineteenth century Bengal, but none so extensively influential.

The formation of the Indian National Congress (INC) in 1885, marked the culmination of several isolated and scattered attempts at nurturing a nationalist consciousness. I have, however, given a few instances from Bengal. I am sure similar attempts were made in other states as well. Even in the formation of the INC, we see the pivotal role played by Janakinath Ghosal (1840 – 1913), husband of the well-known litterateur Swarnakumari Devi (1855 – 1932), elder sister of Rabindranath. According to the memoirs of his elder daughter Hiranmayee, Janakinath was a key presence at the time of the formation of the Congress. Later, Sarala (1872 – 1945), their younger daughter, not only became a part of the Congress, but was also among the foremost figures in Bengal to enthuse young men into the national struggle through cultivation of physical fitness programs. Sarala also worked closely with Swami Vivekananda and Sister Nivedita in some of their philanthropic programs.

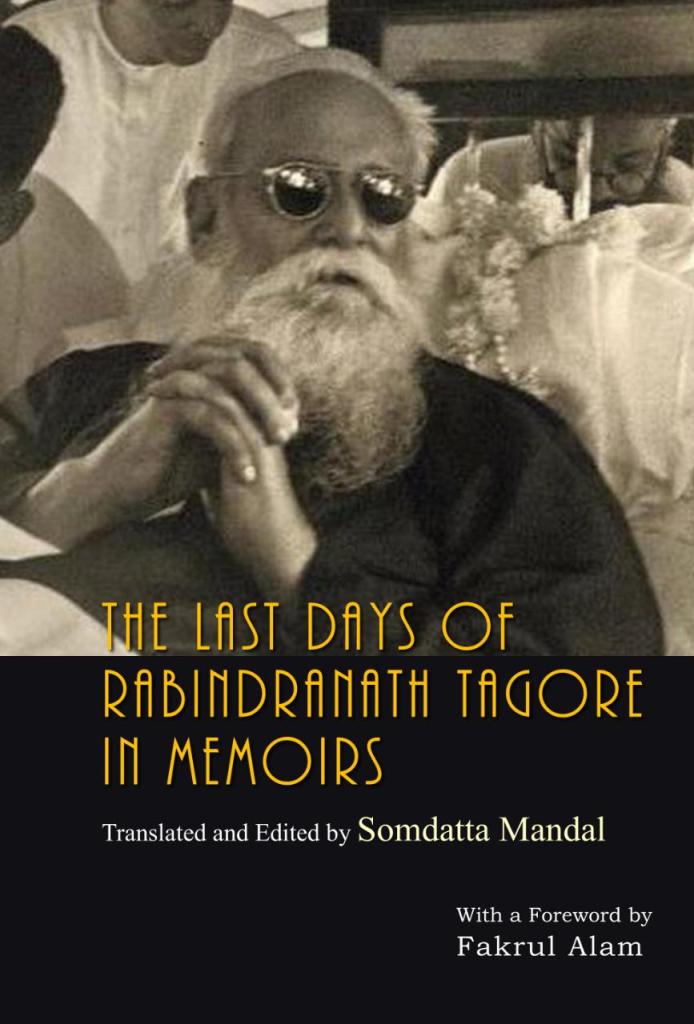

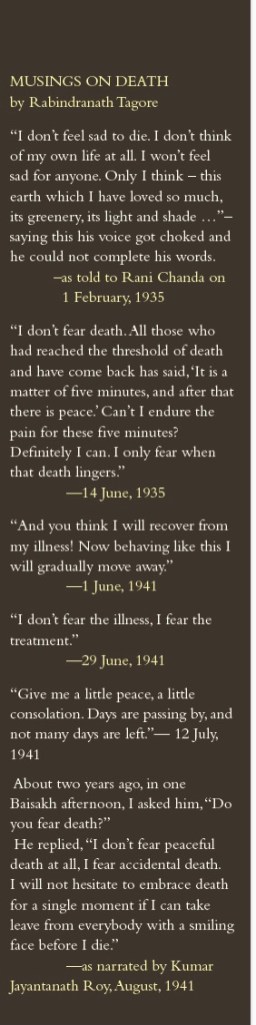

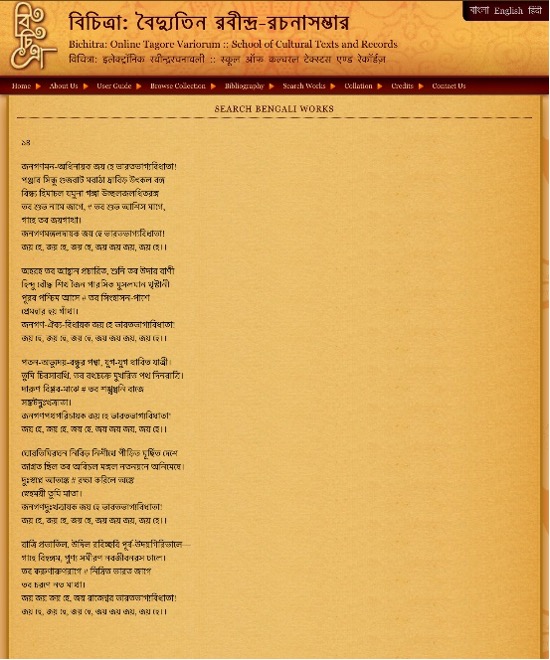

Jana Gana Mana, now venerated as our National Anthem, was most possibly first composed as a hymn, by Rabindranath Tagore. This hymn was first recited on the second day of the annual session of the Indian National Congress on 27th December 1911, by none other than Rabindranath himself. This was followed by a second performance of it in January 1912, in the annual event of the ‘Adi Brahmo Samaj’ or the Brahmo Congregation, and then it was published, for the first time in the January edition of the Tattwabodhini Patrika, which was the official journal of the ‘Adi Brahmo Samaj’, with the title ‘Bharata Bhagya Bidhata’ or ‘the determinant of Bharat’s destiny’. The journal was, at that time, edited by Rabindranath himself. The original song, composed in Bengali, has five stanzas. The Anthem makes use of only the first of the five and usually covers an average time of 52 seconds when sung. The original language has been retained, although its intonation is Devanagiri.

The song is a hymn to the all-pervasive, almighty, and the maker of the country’s destiny, the power of whom presides over her natural boundaries of the Himalayas and other mountains and the rivers, and where resides individuals of all races, cultures and religions. It has been the benefactor, through thick and thin, assimilating the good with the bad, and when the country has been lying destitute in trouble and pain, has extended its hand in empathetic wonder. The sun of Bharat’s destiny will rise again and the pall of darkness shall be drowned in the light of a new dawn – a new beginning and a new hope. Rabindranath did not live to see this dawn, but his visions were realised and honoured by the makers of the Constitution of the Republic of India.

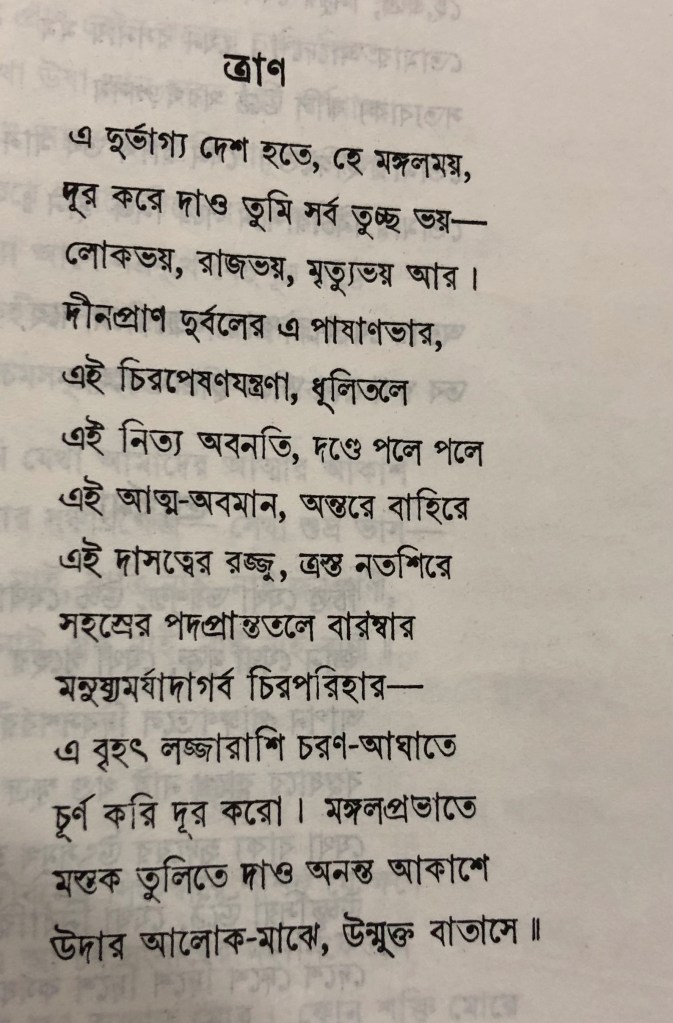

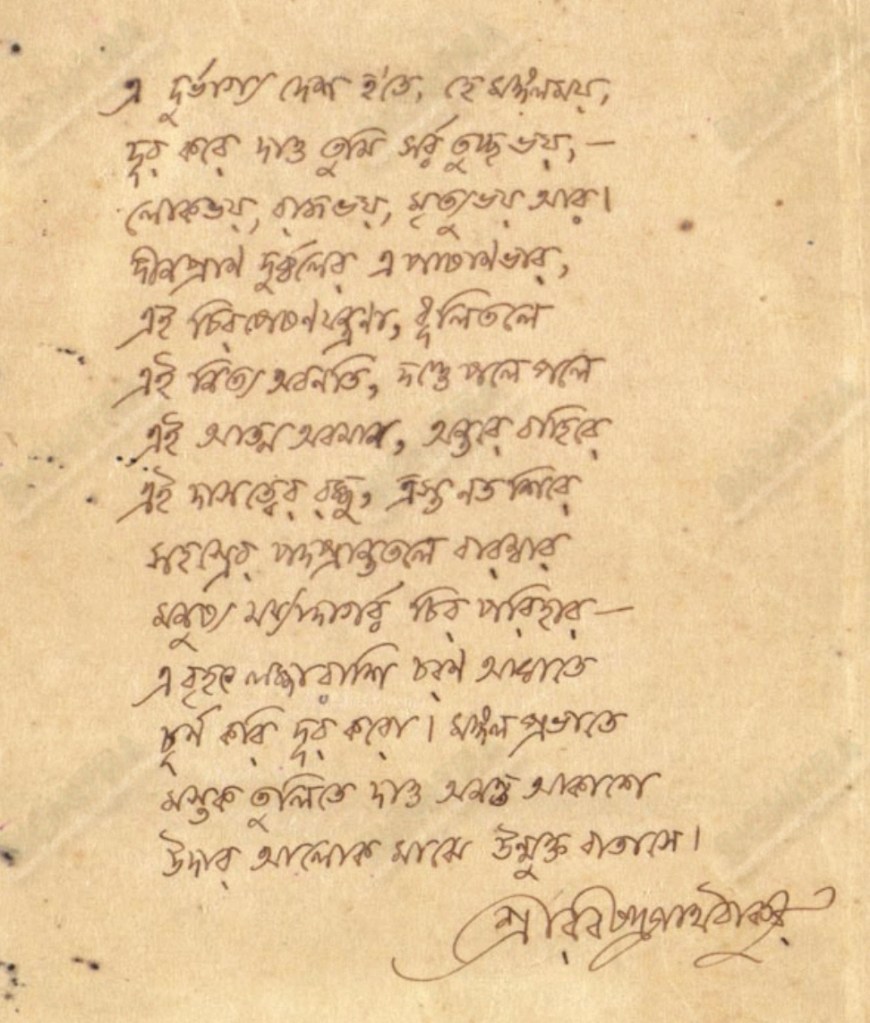

The hymn that originated in the poet’s fiftieth year, perhaps had its germs planted in him through his entire life as the beginning of this essay tries to elaborate. It was only time and the political needs of the country that expedited its utterance in the year 1911. The poet’s vision found embodiment in other and similar creations as well. His Gitanjali (1912) contains the well-known poem, ‘Where the mind is without fear’ (XXXV) –

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high Where knowledge is free Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls Where words come out from the depth of truth Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action — Into that heaven of freedom, my Father let my country awake.

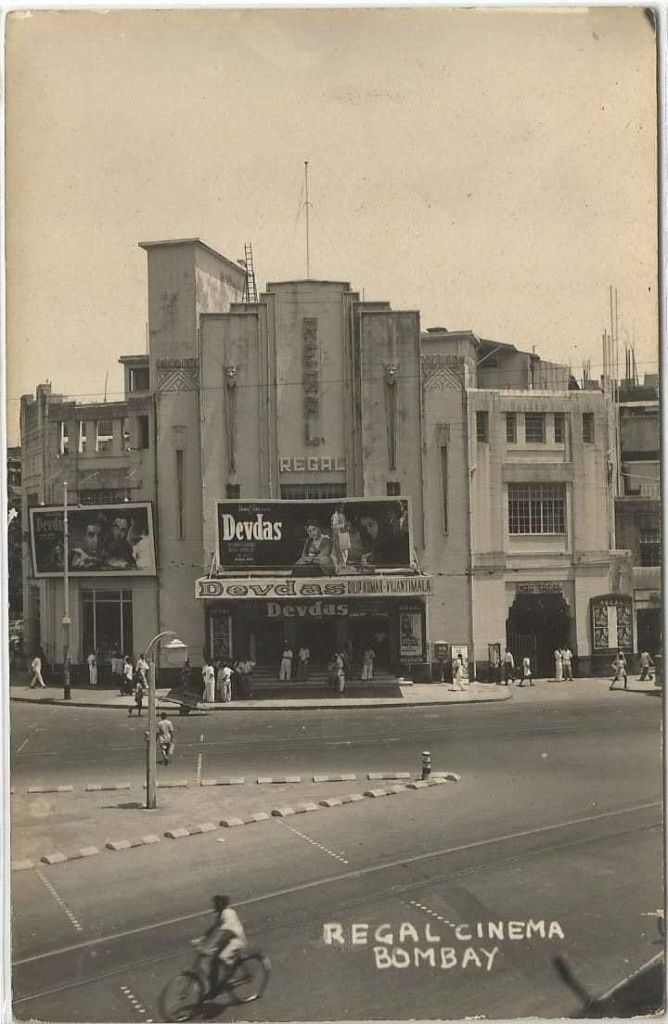

The year in which he composed and first presented Jana Gana Mana, that is 1911, was in many ways a very crucial year in his personal history. As mentioned earlier it was his fiftieth birth-year, and he was gradually beginning to be acknowledged for his poetic greatness in his own land. The following year, that is 1912, he would go to England, with some of his own translations into English, and which would, introduce him to the world as a major poet, among other poets. 1911, was also the year which marked the coronation of King George V and the transfer of the British capital from Calcutta to Delhi. In fact, Rabindranath’s hymn was initially mistaken to be sung in honour of the new Emperor of the British dominions, but was later clarified to be otherwise, and was acknowledged to be a ‘prayer’ for his own native land and independent of such intentions.

The period that we are considering is also a very significant one in Rabindranath’s own consciousness of the nation and his concept of nationalism. In 1910, he published his novel Gora where he underlined the irony inherent in religious exclusivity and bigotry. His protagonist, a staunch votary of Hindu values and virtues, ironically emerges to be an Irish foundling reared in a Hindu home. Through him Rabindranath proves the efficacy of such conservative religious bigotry. His song ‘Bharata Bhagya Bidhata’ pledges to go beyond external divisions of religion and politics, and endorses the value of humanity; nor does it discount the importance of the west, but believes in the fruitful coming together of the best of all worlds. His school at Santiniketan, later to be identified as Visva-Bharati, exemplifies this coming together of the best of all the worlds. In 1919, he delivered a series of lectures on nationalism, which came together in a single volume called Nationalism, and further endorsed his beliefs in finding the nation through culture, history and habits rather than through and in territorial, narrow parochial walls. In Ghare Baire (The Home and the World, 1916), published around the same time, he offers us a critique of the Swadeshi Movement that dominated colonial politics in the first decade of the twentieth century in Bengal. He subtly interweaves a tale of the ‘personal’ with the ‘political’ in the triangular narrative structure of Bimala, Nikhil and Sandip, only to expose the petty hypocrisies that inhere within the grand narratives of ‘nationalism’, ‘patriotism’ and even ‘swadeshi’ at the cost of the common good and humanity at large.

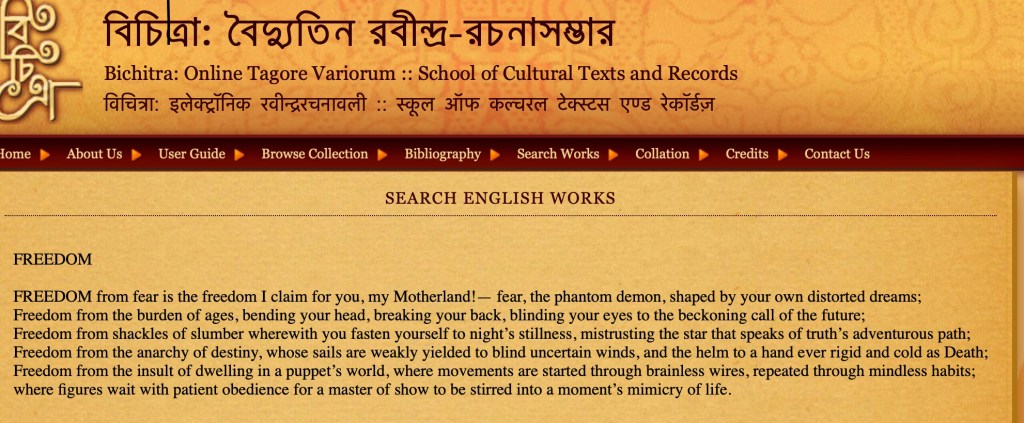

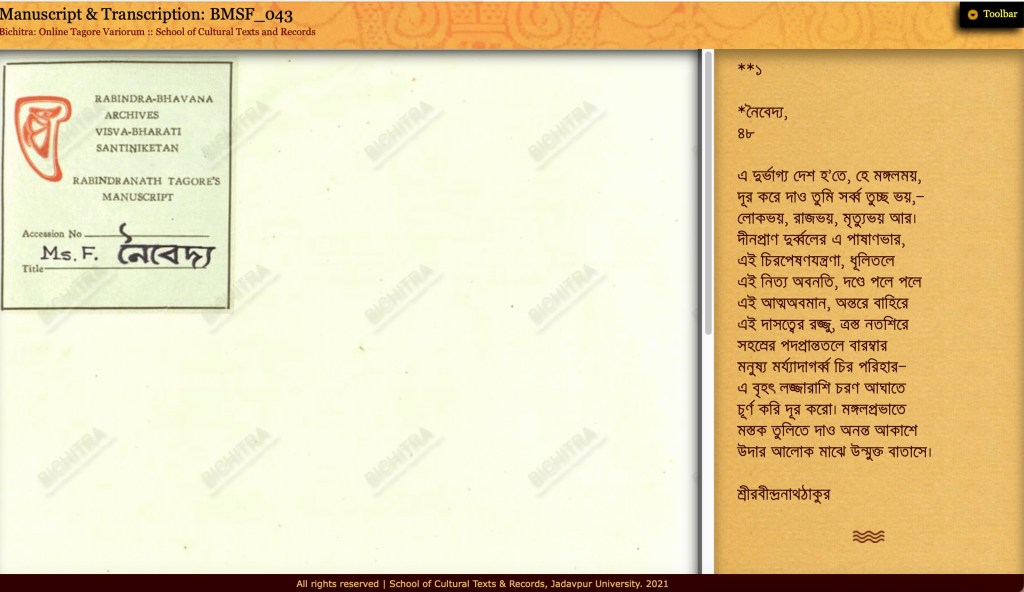

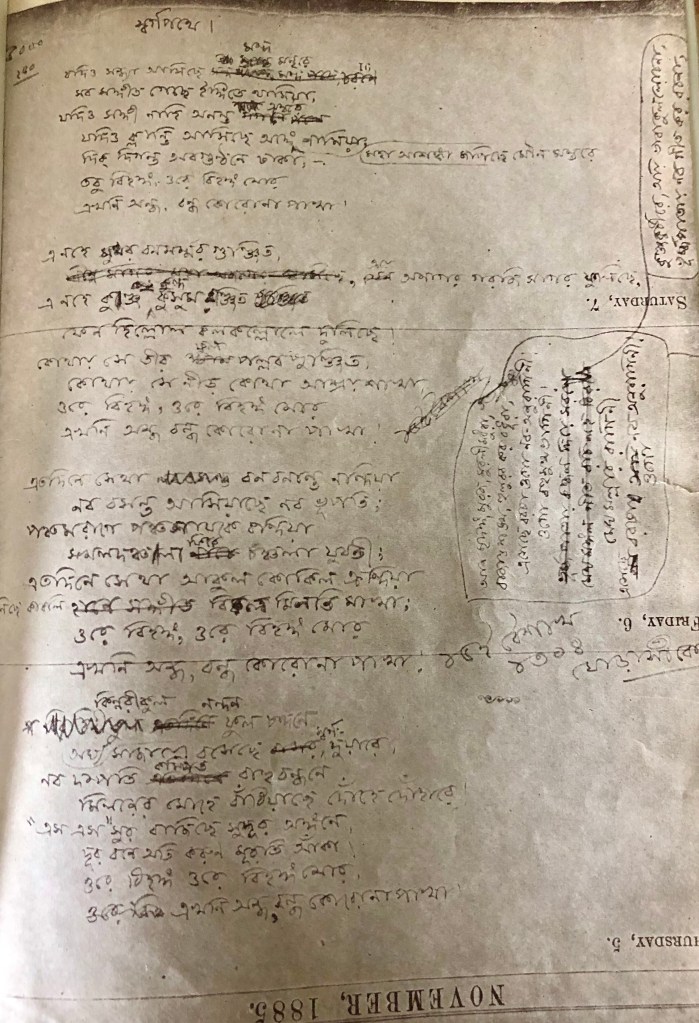

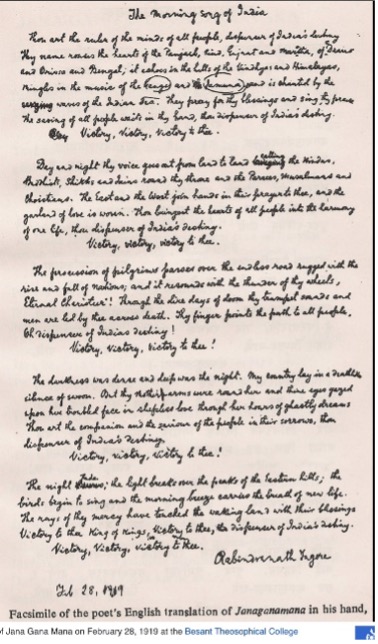

Jana Gana Mana was sung by Sarala Devi Chaudhuri, Rabindranath’s niece and daughter of Janakinath, in 1912, and who had distinguished herself as one of the earliest women nationalists of the country. The song was, then, performed in front of veteran Congress leaders. Outside Bengal, the song was perhaps performed for the first time by Rabindranath in the annual session of Besant Theosophical College in Madanapalle, Andhra Pradesh, on 28th February 1919. The Vice-Principal of the college, Margaret Cousins, was so enthralled by the song that she asked the poet to translate it for her. This Tagore did, and the translation is called ‘The Morning Song of India’. A facsimile image of the same is shown here.

‘Jana Gana Mana’ has been translated into English by noted writer, academic and translator, Aruna Chakravarti. She is perhaps the only person to accomplish this beside the poet himself. The following is the translation made by her, along with the English transliteration of the Bengali original (Songs of Tagore, Niyogi Books):

Leader of the masses. Lord of the minds of men. Arbiter of India’s destiny. Hail to you! All hail! Your name resounds through her sea and land waking countless sleeping souls from Punjab, Sindh, Gurarat, Maratha to Dravid, Utkal, Banga. Her mighty mountains—Himachal, Vindhya, her rivers—Yamuna, Ganga, the blue green sea with which she is girdled; her waves, her peaks, her rippling air seek your blessing, carry your echoes. Oh boundless good! Oh merciful! Hail to you! All hail! At the sound of your call the people assemble from myriad streams of life. Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, Jain. Christian, Parsee and Sikh. East and West stand by your throne hands held in amity, weaving a wreath of fraternal love; of empathy, unity. Oh you who bring us all together! Hail to you! All hail! Nations rise and nations fall on the perilous path of history. And you Eternal Charioteer guide the world’s destiny. Through day, through night, your wheels are heard renting the air with sound, dispelling terror, banishing pain; blowing the conch of peace. Oh true arbiter of India’s fate! Hail to you! All hail! In the deep dark of a turbulent night, when our swooning, suffering land lifted her eyes to your face in hope, she saw your unwavering gaze raining blessings, alight with love, banishing evil dreams. Like a loving mother you held out your arms and changed her destiny. Oh you who wipe out the pain of the masses! Hail to you! All hail! A new day dawns; a new sun rises from the mountains of the east. Song birds trill; new sap of life is borne on the holy breeze. India awakes from aeons of slumber to the strains of your lofty song. Head bowed to your feet oh King of kings! Hail to you! All hail! (Republished with permission from Songs of Tagore, Niyogi Books)

Outside of the country, the song was also performed as the ‘national anthem’ of independent India, under the leadership of Subhas Chandra Bose on the occasion of the founding meeting of the German Indian Society on the 11th of September 1942, in Hamburg, Germany. The Indian Constituent Assembly allowed the performance of Jana Gana Mana on the midnight of 14th August 1947, marking the close of the historical session in the Parliament. It was on the 24th of January, 1950 that only the first stanza of the song was accepted as the National Anthem of independent India. The paeans of a land millennia old, perhaps heading the dawn of all human civilisation alone, is sung through glory to the world over, till date, bearing the torch of an all tolerant, enduring land, by the name of Bharat. Perhaps we still need to be in quest of its philosophy of oneness.

Dr. Anasuya Bhar is Associate Professor of English and Dean of Postgraduate Studies, at St. Paul’s Cathedral Mission College Kolkata, India. She has many publications, both academic and creative, to her credit.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL