Let us imagine a world where wars have been outlawed and there is only peace. Is that even possible outside of John Lennon’s song? While John Gray, a modern-day thinker, propounds human nature cannot change despite technological advancements, one has to only imagine how a cave dweller would have told his family flying to the moon was an impossibility. And yet, it has been proven a reality and now, we are thinking living in outer space, though currently it is only the forte of a few elitists and astronomers. Maybe, it will become an accessible reality as shown in books by Isaac Asimov, Arthur C Clarke or shows like Star Trek and Star Wars. Perhaps, it’s only dreamers or ideators pursuing unreal hopes and urges who often become the change makers, the people that make humanity move forward. In Borderless, we merely gather your dreams and present them to the world. That is why we love to celebrate writers from across all languages and cultures with translations and writings that turn current norms topsy turvy. We feature a number of such ideators in this issue.

Nazrul in his times, would have been one such ideator, which is why we carry a song by him translated by Professor Fakrul Alam. And yet before him was Tagore — this time we carry a translation of an unusual poem about happiness. From current times, we present to you a poet — perhaps the greatest Malay writer in Singapore — Isa Kamari. He has translated his longing for changes into his poems. His novels and stories express the same longing as he shares in The Lost Mantras, his self-translated poems that explore adapting old to new. We will be bringing these out over a period of time. We also have poems by Hrushikesh Mallick translated from Odia by Snehprava Das and a poignant story by Sharaf Shad translated from Balochi by Fazal Baloch.

We have an evocative short play by Rhys Hughes, where gender roles are inverted in a most humorous way. It almost brings to mind Begum Rokeya’s Sultana’s Dream. Tongue-in-cheek humour in non-fiction is brought in by Devraj Singh Kalsi and Chetan Dutta Poduri. Farouk Gulsara and Meredith Stephens write in a light-hearted vein about their interactions with animal friends. G. Venkatesh brings in serious strains with his musings on sustainability. Jun A. Alindogan slips into profundities while talking of “progress” in Philippines. Young Randriamamonjisoa Sylvie Valencia gives a heartfelt account of her journey from Madagascar to Japan. Ratnottama Sengupta travels across space and time to recount her experiences in a festival recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Suzanne Kamata brings a light touch again when she writes about robots serving in restaurants in Japan, a change that would be only fiction even in Asimov’s times, less than a hundred years ago!

Pijus Ash — are we to believe or not believe his strange, spooky encounter in Holland? And we definitely don’t have to believe what skeletons do in Hughes’ limericks, even if their antics make us laugh! Poetry brings on more spooks from Saranyan BV and frightening environmental focus on the aftermath of flooding by Snehaprava Das. We have colours of poetry from all over the world with John Valentine, John Swain, Ahmad Al-Khatat, Stephen Druce, Jyotish Chalil Gopinath, Jenny Middleton, Maria Alam, Ron Pickett, Tanjila Ontu, Jim Bellamy, Pramod Rastogi, John Grey, Laila Brahmbhatt, John Zedolik and Joseph K.Wells.

Fiction yields a fable from Naramsetti Umamaheswararao. Devraj Singh Kalsi takes us into the world of advertising and glamour and Paul Mirabile writes of a sleeper who likes to sleep on benches in parks out of choice! We also have an excerpt from Mohammed Khadeer Babu’s stories, That’s A Fire Ant Right There! Tales from Kavali , translated from Telugu by D.V. Subhashri. The other excerpt is from Swati Pal’s poetry collection, Forever Yours. Pal has in an online interview discussed bereavement and healing through poetry for her stunning poems pretty much do that.

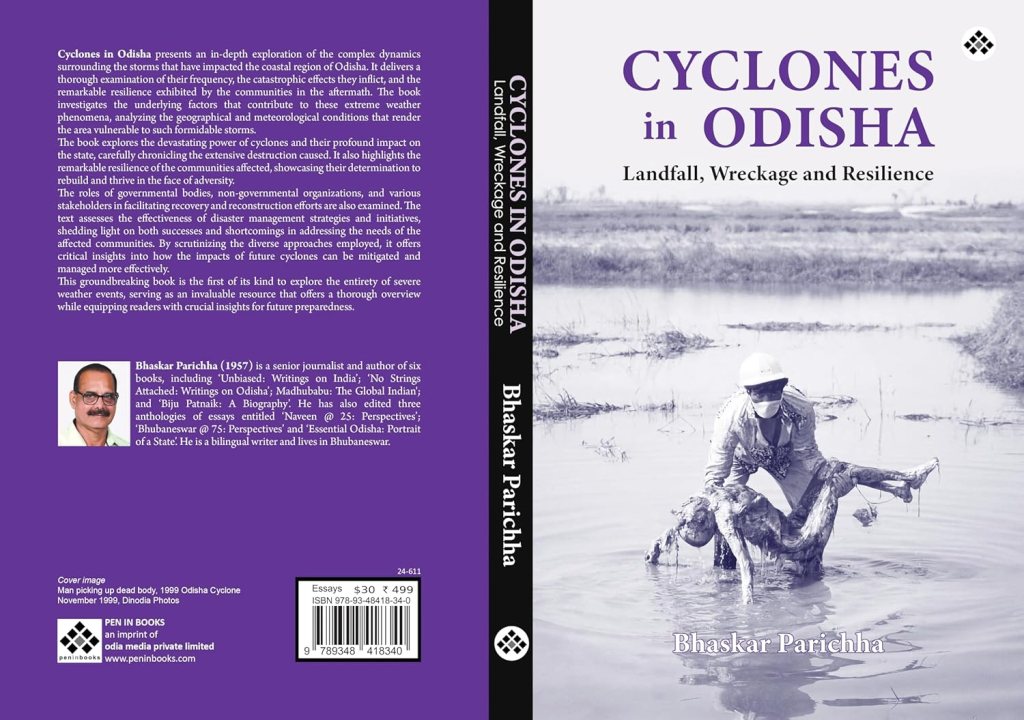

Book reviews homes an indepth introduction by Somdatta Mandal to Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp: Selected Stories, translated from Kannada by Deepa Bhasthi. We have a discussion by Meenakshi Malhotra on Contours of Him: Poems, edited and introduced by Malaysian academic, Malachi Edwin Vethamani, in which she concludes, “that if femininity is a construct, so is masculinity.” Overriding human constructs are journeys made by migrants. Rupak Shreshta has introduced us to immigrant Sangita Swechcha’s Rose’s Odyssey: Tales of Love and Loss, translated from Nepali by Jayant Sharma. Bhaskar Parichha winds up this section with his exploration of Kalpana Karunakaran’s A Woman of No Consequence: Memory, Letters and Resistance in Madras. He tells us: “A Woman of No Consequence restores dignity to what is often dismissed as ordinary. It chronicles the spiritual and intellectual evolution of a woman who sought transcendence within the rhythms of domestic life, turning the everyday into a site of resistance and renewal.” Again, by the sound of it a book that redefines the idea that housework is mundane and gives dignity to women and the task at hand.

We wind up the October issue hoping for changes that will lead to a happier existence, helping us all connect with the commonality of emotions, overriding borders that hurt humanity, other species and the Earth.

Huge thanks to our fabulous team, especially Sohana Manzoor for her inimitable artwork. We would all love to congratulate Hughes for his plays that ran houseful in Swansea. And heartfelt thanks to all our wonderful contributors, without who this issue would not have been possible, and to our readers, who make it worth our while, to write and publish.

Have a wonderful month!

Mitali Chakravarty

CLICK HERE TO ACCESS THE CONTENTS FOR THE OCTOBER 2025 ISSUE

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.