Ogof

Twm Siôn Cati

Cave

is the place

the outlaw graced

with his face

and the remainder of

his ruffianly presence when

he was hiding

from the drab forces of Law

and Order.

Ogof is the Welsh word for Cave,

a word never heard

over the border in England,

and Twm Siôn Cati

is hardly known outside his native

land. I understand

why: he is obscure and there’s no

use being in great

haste to fashion poems about him.

He was a Robin Hood character, I

guess you can say.

If you trudge the wrong way on the

road between

Rhandirmwyn and Soar y Mynydd

you might even

end up as his involuntary guest and

be forced to relax on his stone sofa

while staring down

the barrel of his old flintlock pistol.

He might whistle

through his teeth a merry tune,

but no melodies later

than the 17th Century.

Twm Siôn Cati

never listened to the music

of Erik Satie

or Debussy or Shostakovich.

How could he?

and how can you expect him to

be familiar with their melodies

if it’s true he lived

so long ago in a damp cave?

You have slipped

back through time

and that’s the reason

if not the rhyme

for the mess you find yourself in

now: wave farewell

to modern comforts,

be resigned to a tougher life and

I think you’ll find

solace in the challenge.

Unlike Robin Hood,

Twm Siôn Cati never did

and never would

rob the rich to give to the poor.

He robbed the rich

and the poor as well to give

to himself,

but needless to say,

on any given day he preferred

wealthy victims.

Enjoy

your stay in

Ogof

Twm Siôn Cati

Cave.

Be brave: the scenery is

wonderful,

there are blackberries in

early autumn,

the colourful rocks,

odd as socks

glisten in the rain.

You ought to remain sane

if you accept

your fate: no pain, no gain:

no coin to toss,

no loss.

Twm Siôn Cati has adopted

you as his heir,

you must prepare to follow

in his footsteps

and become a troglodyte,

a night bandit plaguing

the heights of

the region: he planned it this

way all along.

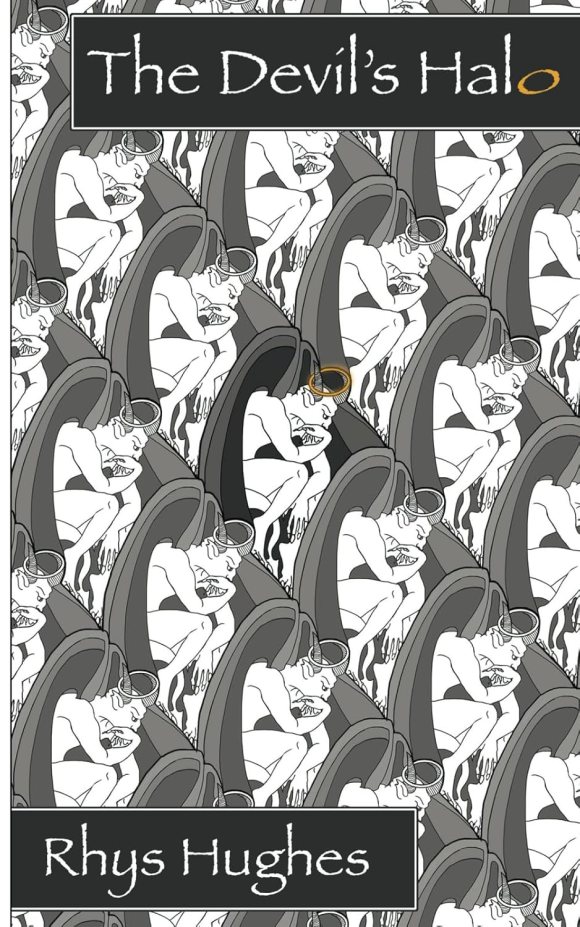

Rhys Hughes has lived in many countries. He graduated as an engineer but currently works as a tutor of mathematics. Since his first book was published in 1995 he has had fifty other books published and his work has been translated into ten languages.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International