By Candice Louisa Daquin

Heortology (the study of festivals) has expanded beyond its initial Christian focus to embrace all festivals and their enduring appeal and necessity in our human culture. Festivals remind us to celebrate, and celebration is a positive experience. The very idea of festivals is ancient. No existing history book is old enough to document when the first festival took place or what its origins were, but it’s a safe bet they had some kind of worship element attached. Modern festivals often also land on old pagan holidays, whilst others are more obvious in their origins. Many who attend festivals have no idea of their origins but go for entirely celebratory reasons. We have learned a lot about the history of varied festivals but another question to consider is: Why are humans drawn to festivals and what do they provide us?

Imagine the ancient world. As much as we think we know now, they knew a tremendous amount also, considering their lack of modern resources. This may well be down to the ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ paradigm. Or that we severely underestimate our ancient ancestors, in our egocentric belief the modern world knows best. Just as we underestimate the knowledge of animals and their abilities to survive. Perhaps we could even say, we have lost the art of survival and wouldn’t know how to, if our computers were offline and our cars did not work and the supermarkets were empty.

What we do know, is the ancients were able to amass a great deal of knowledge, despite seemingly not having easy access like we do today, with our modern telescopes and technology. They had to understand mathematics and science at the very core, to establish theorems on the universe and our place in it. Whilst many were later corrected, it is surprising how many ancient scientists, mathematicians and philosophers, got it right. Almost against all odds. It is fair then to say, we dismiss the richness of the ancient world, and imagine everyone lived ignorant lives, which was not the case. When ignorance did reign, it did so deliberately, with the quashing of knowledge by various religious groups, and resulting periods of ‘dark ages’.

The ancient world was in touch with what it means to be human. Being human isn’t knowing how to work your iPhone or microwave. It’s not having a huge house, with a swimming pool and driving a Lexus. Nor is it eternal youth, fame and glory. Being human is about surviving — just as it is with any animal. When we then add an awareness of our own being, which it is argued, not all animals understand, then we become the modern human we recognise today. A being who has the choice, the ability to reflect and learn, and a tendency to seek beyond themselves. In seeking beyond oneself, we find an innate or shaped desire for ‘more’ and that ‘more’ has often come in the guise of a God-head or spirituality of some kind.

Whether we believe humans are prone to worshipping gods or being spiritual, because Gods actually exists or we just have a propensity to create them, is immaterial. The outcome is the same. The God gene hypothesis proposes that human spirituality is influenced by heredity and that a specific gene, called vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), predisposes humans towards spiritual or mystic experiences, perhaps that is what is at work? In essence a transmitter in our brain that makes it more likely we will believe in God (and could explain why some people do so fervently, whilst others do not). Or perhaps we may find meaning in believing in a spirituality beyond the temporal world. But what we do know is, as long as humans evolved from their primate ancestors, they have formed meaning around some kind of spiritual observance and festivals were tied to this worship.

Why do we do this? We are born part of something (a family) but are also separate (an individual). Perhaps festivals and what they represent, is the coming together of all things: Nature. The seasons. Marking time (birth and death). Marking passages (fertility, menstruation, maturity, marriage, children, dying). These are the cornerstones of meaning, with or without God. I say without God, because for many, their notions of God are tied to nature, so it’s more the world around them than specific deities. For others, it’s the manifold destinies of humanity, or history of deities. But whatever the reason there is a sense of coming together in celebration of being alive, and acknowledging that life. A festival in that sense, irrespective of its actual purpose (the harvest, pagan holidays, etc.) is a ‘fest’ of life. Maybe this is why we can have such a happy time being part of it.

Growing up, neither of my parents liked festivals. They thought they were silly. I remember a street festival I went to as a child, for Fête du Travail (Labour Day) in France. I dressed up as princess and the frog (taking my toy Kermit with me) and felt an excitement like I had never felt before. The throngs of people and other children, the food, the smells, the magicians, the shows and the things to see. It was like walking through a market of treasures. I couldn’t understand why neither of my parents liked this; to me, it felt like a jewel had opened. But for some, festivities are synonymous with rituals and a degree of adherence to religion, even when it’s not. And rather than entering into the spirit of it and enjoying it, they feel what it represents is part of social control.

In France, like many countries, festivals abound. The national Fête du Citron (Menton Lemon Festival) draws crowds from around the world, as does the film screening: Festival de Cannes –near where I grew up — and Fête des Lumières (festival of lights, in Lyon). More traditional festivals include Défilé du 14 Juillet (Bastille Day). In the Middle Ages in France, on Midsummer’s Day, at the end of June, people would celebrate one last party (fête de la Saint-Jean or St. John’s Day). Bonfires would mark this longest day and young men would jump over the flames. This also happened on the first Sunday of Lent (le Dimanche de la Quadragésime), where fires are lit to dance around before carrying lit torches. Religion dominated many of the Autumn/Winter festivals historically.

In France, Christmas, is marked over twelve days with the Feast of the Innocents, the Feast of the Fools, New Year’s Eve and culminates in the Feast of the Kings with its traditional galette des Rois. Events include Candlemas (Chandeleur) with its candlelight process. Likewise, many Christian societies have some celebration connected to Easter (Pâques, in French)) or its Pagan roots. In France (and New Orleans in America) these include Shrove Tuesday (typically Mardi-Gras in America), marking the last feast day before Lent, and many others until Pentecost Sunday. My favorite ‘fest’ was Shrove Tuesday (also known as Fat Tuesday or Pancake Day, in other countries) because my grandma would make pancakes, despite our being Jewish. The notion was to eat before Christian Lent and a period of fasting, which has much in common with Muslim beliefs too (unsurprisingly since God is one in the Jewish, Christian and Muslim faiths). In America, they serve fish options every Friday for much the same reason.

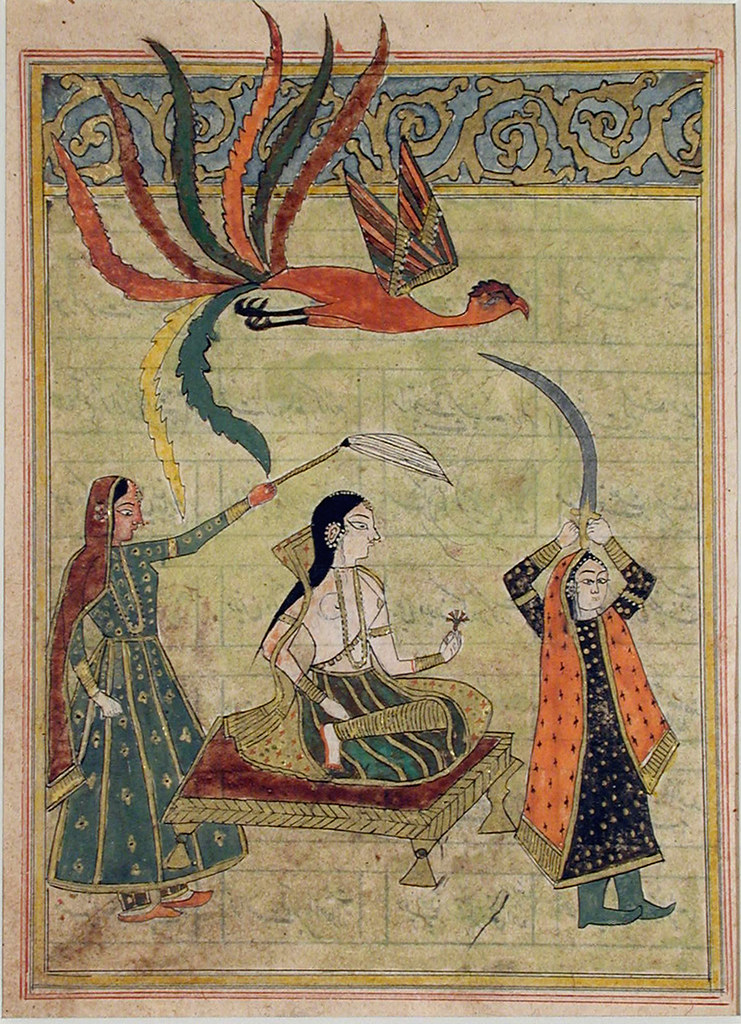

Far more impressive and immersive festivals occur in India, with Hinduism celebrating among the highest number of festival days in the world. Over 50 festivals are celebrated throughout India by people of different cultures and religions. These Indian festivals form an integral part of the rich heritage of the country. The ancient Hindu festival of Spring, colors and love known as Holi is one. “Holi is considered as one of the most revered and celebrated festivals of India and it is celebrated in almost every part of the country. It is also sometimes called as the ‘festival of love’ as on this day people get to unite together forgetting all resentments and all types of bad feeling towards each other.” Holi is celebrated on the last full moon in the lunar month of Phalgun, the 12th month in the Hindu calendar (which corresponds to February or March in the Gregorian calendar).

With social media, more of the world have been granted access to the visual beauty of Holi – “This ancient tradition marks the end of winter and honors the triumph of good over evil. Celebrants’ light bonfires, throw colourful powder called gulal, eat sweets, and dance to traditional folk music.” One of the most popular legends in Hindu mythology says the Holi festival marks Lord Vishnu’s triumph over King Hiranyakashyapu, who killed anyone who disobeyed him or worshipped other gods. With coloured powder thrown on people as part of the celebration, many countries now celebrate Holi just as Indians may celebrate Halloween or Día de Muertos. The crossover effect may seem to dismiss the individualistic cultural value and smack of appropriation but, in reality, it’s more a sign of respecting other cultures, learning about them, and celebrating with them.

Mexico, which I live near to now, celebrates over 500 festivals yearly and consequently is one of the most festive cultures in the world. In San Antonio, TX, where I currently live, we celebrate many of these fiestas, alongside American ones. The most popular being Día de Muertos, Día de la Virgen de Guadalupe, Cinco de Mayo and Día de la Candelaria, (like the French Candlemas, celebrated after Three Kings Day, which is a bigger holiday than Christmas in Mexico). The variables in cultures are fascinating. In San Antonio, we get a huge influx of Mexican tourists over Christmas because they aren’t home celebrating as they do so a few days later. We have a fiesta in San Antonio that is much like those in Mexico, due to our large Mexican population and it’s heartening to see the merging of the two.

As a child I celebrated the Jewish Pilgrim Festivals—Pesaḥ (Passover), Shavuot (Feast of Weeks, or Pentecost), and Sukkoth (Tabernacles)—and the High Holidays—Rosh Hashana (New Year) and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement). But I attended a school that celebrated all faiths so we also celebrated Ramadan, the Muslim sacred month of fasting, akin to Christian Lent. Growing up, my friends of all faiths, celebrated Eid-ul-Fitr or simply Eid which is among the religious festivals for the Muslim community, marking the end of Ramadan. This festival is celebrated on the day after seeing the night crescent moon with devotees offering prayers at mosques and then feasting with their near and dear ones.

We would also celebrate Kwanzaa, which is a worldwide celebration of African culture, running from December 26 to January 1, culminating in a communal feast called Karamu. Its creator was a major figure in the black power movement in America, “Maulana Karenga created Kwanzaa in 1966 during the aftermath of the Watts riots as a specifically African-American holiday. Karenga said his goal was to ‘give black people an alternative to the existing holiday of Christmas, and give black people an opportunity to celebrate themselves and their history, rather than simply imitate the practice of the dominant society.’”

Are we socially controlled when we attend festivals? Given we have a choice, I would say no. Someone who chooses to be part of something, isn’t signing up for life, they’re passing through. Since my childhood I have been lucky enough to have attended many festivals in many countries. For me it is a reaffirming experience, seeing people from all walks of life come together in happiness. I like nothing better than dressing up and meeting with others and walking through streets thronged with people. Be they carnivals, even political events, there is an energy that you rarely feel anywhere else.

The May Pole festival, believed to have started in Roman Britain around 2,000 years ago, when soldiers celebrated the arrival of spring by dancing around decorated trees thanking their goddess Flora, is an especially interesting festival because it is still practiced almost as in ancient times. The ribbons and floral garlands that adorned it represent feminine energy and the beauty of the ritual is enduringly something to behold.

Likewise, another event ‘Guy Fawkes Night’ is steeped in ritual and British history, with much symbolism in the burning of straw dummies that are meant to represent Guy Fawkes thrown onto bonfires. However, the act of throwing a dummy on the fire to represent a person, has also been done since the 13th century to drive away evil spirits. What most people seem to take away from Guy Fawkes Night are the abundant fireworks in a beautiful night sky, alongside children and families holding sparklers and eating horse chestnuts in the cold, wrapped up in mittens. It’s a ritual that is beloved and a chance to ‘be festive’ even if it’s not a specific festival. As much as anything, it marks time, another year, another November, and gives wonderful memories. If we didn’t mark time or have those memories, we’d still have others, but there is an ease with festivals because they do it for us, unconsciously.

Young collegiates often attend festivals that involve dancing and sometimes drugs. Again, this is not a modern occurrence but has been going on for years, as rites of entering adulthood. The desire of the young to get out and meet others and dance and enjoy life, is primeval, and possibly a part of who we are as humans, marking a potent stage in our lives. Recently I went to a birthday party at a night club. I observed the diverse throngs of party goers and reveled in that abundant diversity. In just one night I saw: Pakistani women in saris, Japanese girls in anime costumes with ears, a pagan woman with huge, curled bull horns and floor length leather dress, Jamaican families in neon shorts and t-shirts, transgender wearing spandex dresses and big wigs, Hispanic Westsider’s filled with tattoos, and gold necklaces, Lesbian and gay couples holding hands. Old couples in sensible church clothes including one old black man with a pork pie hat and a waist coat.

I thought of all the diversity that had attended this club to dance the night away. All ages, all genders and backgrounds and ethnicities, and I thought how wonderful it was that one place could hold them all. In many ways this is the essence of a festival, especially nowadays where anyone can attend most festivals. Years previous, they were segregated by subject. Only those followers of that subject usually attended and you could be harmed if you tried to attend and were an outsider. The advantage we have today is we are more accepting of outsiders and when you attend festivals today, you see a wide range of people. Maybe this is the best opportunity we have to put down our differences and celebrate our similarities.

When I lived in Canada, I loved the homage paid to different seasons in varied outdoor festivals, where shaking off the lethargy of Winter, Canadians would celebrate with fairgrounds, amusements, shows and food among other things. It was like a period of renewal. Likewise, during my time in England, the Notting Hill Carnival, celebrated the Afro Caribbean culture, so essential and entrenched in English culture, with gorgeous street displays and floats, as well as some of the best music around. The idea of welcoming everyone into the fold, helps to remove any tensions between cultures and promote a feeling of unity, whilst not denying the unique properties of those cultures and ensuring they are promoted in their adopted countries. It may be idealistic and not entirely accurate, but it’s a better step than ignoring those myriad cultures exist.

As Halloween and Día de Muertos is fast approaching, I am thinking of how many of my neighbours attend these parties, despite some of them being from very conservative churches. Just last year, we all sat outside in the green spaces and had a mini fireworks display. I sat next to my little 4-year-old neighbour and watched her face as the older kids, dressed in all sorts of costumes, shrieked at the fireworks, and ran around with neon bangles, throwing glow powder at each other. I saw how inculcated we are, since childhood, but despite this I truly believe festivities are in our hearts, even if we weren’t introduced to them at an early age. Children mark their growing up by the events of their lives and it’s not just their birthday they celebrate but the touchstones of their respective culture and nowadays, many other cultures.

My Egyptian grandfather used to tell me about the Nile festival which celebrated the flooding of the river and the replenishing of life in Egypt. Without the Nile, Egypt couldn’t exist, and the ancients knew this. They employed methods to enhance the flooding and gave thanks for it. Gratitude like this can be found in many celebrations, including the American Thanksgiving (although this is a double-edged sword, given the history of genocide of the Native Americans by European pilgrims and invaders) and Harvest throughout the world. A celebration of life through food with music, is at the core of the human ability to endure and overcome hardship. More recently many of us celebrated healthcare workers by singing out of our windows and putting messages of thanks in our windows. We do this because it symbolizes essential parts of our lives, without which we would suffer.

Owing to its melting pot past, Egypt celebrates the Coptic Orthodox Christmas, the more ancient Abu Simbel Sun Festival that is akin to the Egyptian Sun God Ra (who in turn was one inspiration for the Christian God many years later), Sham Ennessim, the national festival marking the beginning of spring, as it originates from the ancient Egyptian Shemu festival, Ramadan and the Muslim Eid al-Adha (honoring the willingness of Ibrahim (Abraham) to sacrifice his son Ismail (Ishmael) as an act of obedience to Allah’s command). As a Jew, my grandfather’s family celebrated Passover, the festival celebrating the Jews Exodus from Egypt, despite our family still living there! Nowadays it is no longer safe to live in Egypt as a Jew but the memory of all people’s experiences is preserved through ancient festivals and events, marking our shared history.

Before the advent of mass-produced entertainment, festivals were also a highlight in any village or town, because they were entertainment. Traveling theatres and shows for children, even book sellers and traders of items not commonly found locally, could be bartered or purchased at such events and it was almost a spilling out from the market square economy that kept such villages alive. Perhaps evolving from our natural tendency to barter for things we want, we evolved to invite others from outside to come for specific events to gain greater reach. With this trading and bartering, came the accoutrements such as eating, drinking, dancing. Not only did this increase diversity and knowledge of foods and drinks from other locales, but brought people who may otherwise not meet, together into a camaraderie.

Sharing stories is also part of festivals, by way of theatre, or more improvised scenarios. It is at our heart to pass on oral knowledge and we haven’t lost that desire. We may do this now via YouTube more than face to face (which is a shame), but the desire to get out and talk directly, is innate, as evidenced by how many people have done just that since Covid 19 restrictions are eased. Religion, folklore, ritual and a desire for escapism, alongside our desire to celebrate things or others (saints, gods, seasons, harvest) are all reasons why festivals endure. Just like children will instinctively dance when music is played, maybe it is our innate nature to enjoy festivals because they foster inter-relationships we all crave to some degree. We may be diverse and believe different things, but we can also come together and respect the perspectives of others. Never more so than through our shared love of celebration.

.

Candice Louisa Daquin is a Psychotherapist and Editor, having worked in Europe, Canada and the USA. Daquins own work is also published widely, she has written five books of poetry, the last published by Finishing Line Press called Pinch the Lock. Her website is www thefeatheredsleep.com

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.