Salma A. Shafi writes from ground level at Noakhali

The Greater Noakhali region of Bangladesh is experiencing one of the most severe flood and water-logging crises in recent memory, driven by persistent heavy rainfall since mid-August 2024. The flood affected more than 5 million people, submerging houses, roads, and marketplaces, and leaving large portions of the region inundated. A total of 71 people, including women and children, lost their lives in the flood affected areas. With water levels reaching alarming heights, the disaster has raised significant concerns about vulnerability of the region for future flooding.

Almost every year floods occur in Bangladesh, but the intensity and magnitude vary from year to year. Their nature causes and extent of destruction gives them various definitions such as river flood, rainfall flood, flash flood, tidal flood, storm surge flood. The term manmade flood is a recent phenomenon attributed to encroachment on vital water channels, such as canals and wetlands sometimes for construction of roads and bridges and frequently for fish cultivation, hatcheries and shrimp farming.

Context of recent flood in Bangladesh

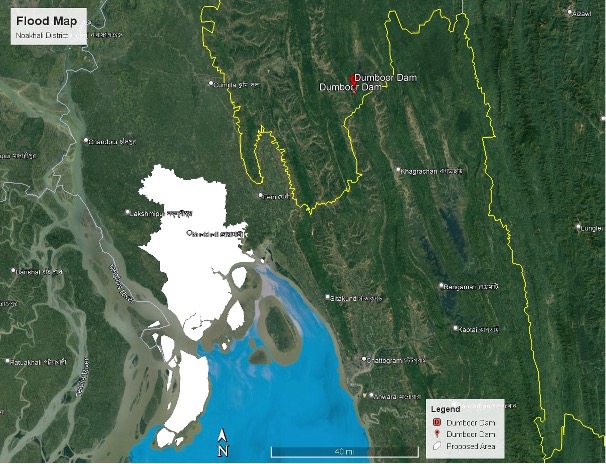

Since August 20, 2024, Bangladesh has been facing severe flooding triggered by continuous heavy rainfall and, according to the Bangladesh Ministry of External Affairs, water releases from Dumbur Dam, upstream in Tripura, India[1], a claim that is denied by the Indian government. Tripura also suffered severe floods and landslides[2] from this August. The flood impacted several districts in Bangladesh, including Feni, Noakhali, Comilla, Lakshmipur, Brahmanbaria, Cox’s Bazar, Khagrachhari, Chattogram, Habiganj, and Moulvibazar. By August 23, 2024, the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief reported that floods had affected 4.5 million people across 77 upazilas in 11 districts. Nearly 194,000 people, along with over 17,800 livestock sought refuge in 3,170 shelters as the crisis continued.

In addition to widespread displacement, the floods led to tragic fatalities, with deaths reported across multiple districts. Communication with key river stations, such as Muhuri[3] and Halda[4], were completely severed, hampering collection of vital data necessary for relief and rescue operations. The extensive flooding has caused significant damage to property, crops, and infrastructure, displacing thousands of families. The disruption to transportation and agriculture deepened the humanitarian crisis, demanding immediate action to mitigate long-term impacts of disaster on the affected communities.

The flood situation in Noakhali District worsened due to continuous heavy rainfall and rising water levels of the Muhuri River. The district Weather Office recorded 71 mm of rainfall within 24 hours, exacerbating the flooding. Approximately 2 million people were stranded as floodwaters submerged roads, agricultural fields, and fish ponds. Seven municipalities in the district went underwater, with widespread waterlogging affecting both rural and urban settlements.

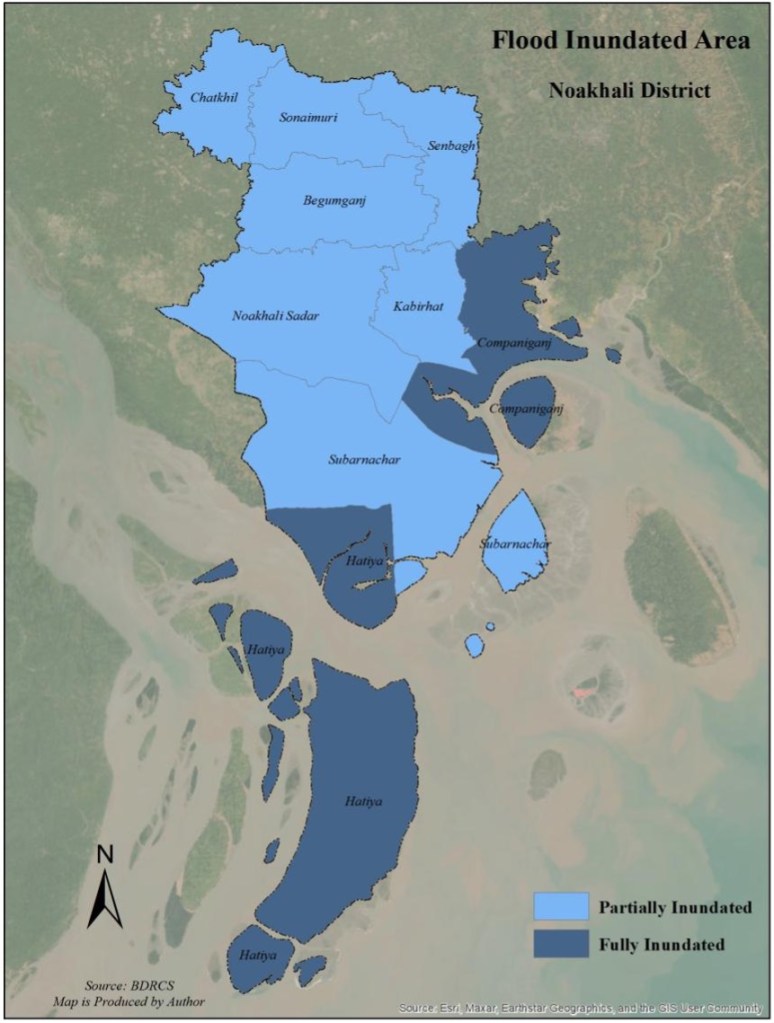

On September 1, 2024, the Noakhali Meteorological Office reported a staggering 174 mm of rainfall within a 12-hour period, causing widespread flooding and waterlogging across low-lying areas. The worst-affected upazilas include Noakhali, Senbagh, Sonaimuri, Chatkhil, Begumganj, Kabirhat, Companiganj, and Subarnachar, where over 2.1 million people were stranded. Additionally, more than 264,000 individuals sought refuge in emergency shelters and school buildings. The prolonged water-logging devastated local economy, particularly the agricultural sector, where vast areas of farmland, including Aman rice seedbeds and vegetable fields, were submerged, jeopardizing livelihoods of farmers and disrupting essential food production for a prolonged period.

With 90% of Noakhali district’s population impacted by this flash flood, the region faced critical humanitarian and environmental emergency. An analysis of the causes and consequences of flood and waterlogging in Greater Noakhali reveals an interplay of meteorological, infrastructural, and environmental factors coupled with geographic location of Bangladesh and the geo morphology of the river systems of the region. Bangladesh and India share 54 rivers of which the Teesta, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Meghna forming the GBM basin are the most important. This river basin is one of the largest hydrological regions in the world and stretches across five countries Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India and Nepal. This basin area is home to 47 percent of the Indian population and 80 percent of the Bangladeshi population. Food security, water supply, energy and environment of both countries are dependent on the water resource of the rivers.

Uncertainty and Challenges in Flood situation

During the monsoon periods development of a low-pressure system over northern Bangladesh can bring very heavy to extremely heavy rainfall in Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura posing great threat to flood-prone areas in Bangladesh. These overlapping weather patterns and regional dynamics create highly uncertain and dangerous situation, making it difficult to coordinate an effective response and leave millions of people vulnerable to worsening flood conditions.

Flooding in Noakhali region resulted from heavy rainfall and floods in western Tripura in August and as per MEA[5] news broadcast that the Dumbur Dam, a hydro power project had been, “auto releasing”, water as a consequence of the rainfall. The Dumbur Dam in Tripura is located far from the border about 120km upstream of Bangladesh. It is a low height dam (30m) that generates power and feeds into a grid from which Bangladesh also draws 40MW power. There are three water level observation sites along the 120km river course. As per news from the monitoring agencies excess water from the Gumti reservoir was automatically released through the spillway once it crossed the 94m mark which is the reservoirs full capacity. It is a known fact there is no comprehensive regional mechanism for transboundary water governance or multilateral forum involving the five Asian nations. The lower riparian nations particularly India and Bangladesh are therefore the worst sufferers.

Key Impact Areas in Bangladesh:

The flood in the Noakhali region was caused by overflow of water from the large catchment areas downstream of the Dumbur Dam. While river channels were not deep enough to accommodate the excess water, unplanned constructions on rivers and canals caused the water to spill into settlement areas causing humanitarian crisis unseen in decades. Kompaniganj and Hatiya upazilas (sub-districts) were completely inundated by floodwaters, while Subarna Char, Sonaimuri, Noakhali Sadar, Kabir Hat, and Senbag upazilas were partially affected. The flooding submerged homes, roads, and marketplaces, with water levels reaching roof levels in the high flood zones, waist-deep in some areas and knee-deep inside most homes. The rising floodwaters devastated farmlands, particularly Aman paddy seedbeds and vegetable fields, swept away, a large number of the cattle, poultry including the sheds which sheltered them.

Current Challenges

The ongoing flood crisis in Bangladesh faces several critical challenges. One of the most immediate issues is the submersion of roads and the disruption of communication networks, which has significantly hindered relief efforts. The situation is fluid, with new districts continuously being affected, complicating the delivery of aid and emergency services to those in need. This has also resulted in delays in evacuations, leaving many communities stranded without access to basic necessities.

Another key challenge is the conflicting information from different meteorological agencies. The Bangladesh Meteorological Department and the Flood Forecasting and Warning Center (FFWC) have issued varying reports regarding upcoming weather conditions. This uncertainty is affecting the preparedness of the affected populations, making it difficult for them to take timely and appropriate measures to protect themselves and their property.

Geo-political Tension in River Management in Bangladesh

Bangladesh, known as one of the most climate-vulnerable nations globally is facing increasing geopolitical challenges due to its strategic location on the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta. Besides, annual monsoon floods, flash flood, particularly in northeastern districts of Sylhet, Feni and Cumilla, Noakhali are exacerbated by water releases from upstream dams, such as the Dumbur Dam. These actions have intensified tensions between Bangladesh and India, highlighting the complex dynamics of transboundary river management.

Despite legal recognition of rivers as living entities, both nations continue to exploit these water resources through infrastructure projects that disrupt natural river flows. Extensive dam and hydropower projects on shared rivers have caused significant environmental and social injustices downstream, impacting both ecosystems and livelihoods. This situation reflects a broader pattern of unilateral control and inadequate cooperation in water management, which contradicts international agreements and hinders equitable water sharing.

The Bangladesh-India Joint River Commission, established in 1972, is yet to resolve these critical issues. The recent floods have further underscored the need for more effective communication and cooperation between the two nations to prevent future disasters. As calls for water justice grow louder, there is increasing pressure on both countries to remove barriers and ensure the free flow of rivers across borders, upholding the principles of transboundary water governance and protecting the rights of those affected downstream.

[1] India disputes this claim saying that they have been releasing the same quantity of water for the last fifty years. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/natural-disasters/india-has-no-role-in-bangladesh-flood-dumbur-dam-opens-automatically-for-last-50-years-tripura-official https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/india-refutes-claims-causing-floods-bangladesh-3683526

[2] The floods displaced 65,000 people and killed 23 in Tripura. https://www.reuters.com/world/india/floods-landslides-indias-tripura-displace-tens-thousands-2024-08-23/

[3] A river that starts in Tripura and flows down to Feni. Also, Muhuri Irrigation Project is Bangladesh’s second largest irrigation project. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhuri_Project

[4] The Halda River is the breeding ground for carp and fishermen harvest the carp eggs. https://bsmrau.edu.bd/seminar/wp-content/uploads/sites/318/2020/08/003-Umme-Hani-Sharanika-seminar-paper.pdf

[5] Ministry of External Affairs, in this case Bangladesh.

Salma A. Shafi is an architect and urban planner. She did her MSc. in Urban Planning from AIT, Bangkok, Thailand and has a Bachelor of Architecture (B. Arch.) degree from BUET, Dhaka. Salma Shafi has extensive experience in urban research and consultancy, specialising in urban land use and infrastructure planning, housing and tenure issues. She is a well-known researcher in the field of urbanisation and urban planning. Urban Crime and Violence in Dhaka published by the University Press Limited (2010), Housing Development Program for Dhaka City, Centre for Urban Studies, Dhaka (2008) and Feroza, a biography of her mother published by Journeyman (2021).

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International