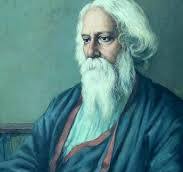

Translations are like bridges. Three years ago, we decided to start a bridge between Tagore’s ideas and the world that was unfamiliar with his language, Bengali. He has of course written a few pieces in Brajbuli too. We started our journey into the territory of Tagore translations with Aruna Chakravarti’s Songs of Tagore. Now we have expanded hugely this section of our translations with many prose pieces and more translations of his lyrics and poetry by writers like Aruna Chakravarti, Fakrul Alam, Radha Chakravarty, Somdatta Mandal, Himadri Lahiri, Ratnottama Sengupta, Chaitali Sengupta and Nishat Atiya other than our team’s efforts. To all these translators our heartfelt thanks. We share with you their work celebrating one of the greatest ideators of the world.

Prose

Stories

.Aparichita by Tagore :This short story has been translated as The Stranger by Aruna Chakravarti. Click here to read.

Musalmanir Galpa (A Muslim Woman’s Story): This short story has been translated by Aruna Chakravarti. Click here to read.

One Small Ancient Tale: Rabindranath Tagore’s Ekti Khudro Puraton Golpo (One Small Ancient Tale) from his collection Golpo Guchcho ( literally, a bunch of stories) has been translated by Nishat Atiya. Click here to read.

Bolai: Story of nature and a child translated by Chaitali Sengupta. Click here to read.

Humorous Skits

(All translated by Somdatta Mandal)

Playlets by Rabindranath Tagore : Click here to read.

The Ordeal of Fame: Click here to read.

The Funeral: Click here to read.

The Welcome: Click here to read.

The Treatment of an Ailment: Click here to read.

Non-fiction

Baraf Pora (Snowfall) : This narrative gives a glimpse of Tagore’s first experience of snowfall in Brighton and published in the Tagore family journal, Balak (Children), has been translated by Somdatta Mandal . Click here to read.

Travels & Holidays: Humour from Rabindranath: Translated from the original Bengali by Somdatta Mandal, these are Tagore’s essays and letters laced with humour. Click here to read.

Himalaya Jatra ( A trip to Himalayas) :This narrative about Tagore’s first trip to Himalayas and beyond with his father, has been translated from his Jibon Smriti (1911, Reminiscenses) by Somdatta Mandal. Click here to read.

Raja O Praja or The King and His Subjects, an essay by Tagore, has been translated by Himadri Lahiri. Click here to read.

Library: A part of Bichitro Probondho (Strange Essays) by Rabindranath Tagore, this essay was written in 1885, translated by Chaitali Sengupta. Click here to read.

Book Excerpts

The Parrot’s Tale: Excerpted from Rabindranth Tagore. The Land of Cards: Stories, Poems and Plays for Children, translated by Radha Chakravarty, with a foreword from Mahasweta Devi. Click here to read

Rabindranath Tagore Four Chapters: An excerpt from a brilliant new translation by Radha Chakravarty of Tagore’s controversial last novel Char Adhyay. Click here to read.

Farewell Song :An excerpt from Radha Chakravarty’s translation of Tagore’s novel. Click here to read.

An excerpt from ‘Kobi’ and ‘Rani’: Memoirs and Correspondences of Nirmalkumari Mahalanobis and Rabindranath Tagore, translated by Somdatta Mandal, showcasing Tagore’s introduction and letters. Click here to read.

Letters from Japan, Europe & America :An excerpt from letters written by Tagore from Kobi & Rani, translated by Somdatta Mandal. Click hereto read.

Gleanings of the Road: Book excerpt brilliantly translated by Somdatta Mandal. Click here to read.

Songs and Poems

Songs of Seasons: Translated by Fakrul Alam

Bangla Academy literary award winning translator, Dr Fakrul Alam, translates seven seasonal songs of Tagore. Click here to read.

- Garland of Lightening Gems (Bajromanik Diye Gantha)

- In The Thunderous Clouds (Oi Je Jhorer Meghe)

- The Tune of the New Clouds (Aaj Nobeen Megher Shoor Legeche)

- The Sky’s Musings (Aaj Akashe Moner Kotha)

- Under the Kadamba Trees (Esho Nipo Bone)

- Tear-filled Sorrow (Ashrubhara Bedona)

Endless Love: Tagore Translated by Fakrul Alam

Ananto Prem (Endless Love) by Tagore, translated from Bengali by Professor Fakrul Alam. Click here to read.

Giraffer Baba (Giraffe’s Dad), a short humorous poem by Tagore, has been translated from Bengali by Professor Fakrul Alam. Click here to read.

Oikotan (Harmonising) has been translated by Professor Fakrul Alam and published specially to commemorate Tagore’s Birth Anniversary. Click hereto read.

Monomor Megher O Shongi (or The Cloud, My friend) has been translated by Professor Fakrul Alam. Click here to read.

Professor Fakrul Alam has translated Tomra Ja Bolo Tai Bolo, Hridoy Chheele Jege and Himer Raate — three songs around autumn from Click here to read.

Tagore’s Achhe Dukhu, Achhe Mrityu, (Sorrow Exists, Death Exists) has been translated from Bengali by Fakrul Alam. Click here to read.

Colour the World: Translated by Ratnottama Sengupt: Rangiye Diye Jao, a song by Tagore, transcreated by Ratnottama Sengupta. Click here to read.

Bhumika (Introduction) by Tagore has been translated by Ratnottama Sengupta. Click here to read.

On behalf of Borderless Journal

Esho, He Baisakh, Esho Esho (Come Baisakh: A song to welcome the Bengali New Year) Click here to read.

Tagore Songs in Translation. Click here to read the next five.

- Kothao Amar Hariye Jawa Nei Mana ( Losing myself)

- Akash Bhora Shurjo Tara (The Star-studded Sky)

- Krishnokoli ( Inspired by a girl who lives in a village)

- Phoole Phoole Dhole Dhole (The Swaying Flowers)

- Shaongagane Ghora Ghanaghata (Against the Monsoon Skies, Brajbuli to English)

Tagore’s Diner Sheshe Ghoomer Deshe (At the close of the day, in the land of sleep).Click here to read the translation.

Tagore’s Amar Shonar Horin Chai (I want the Golden Deer). Click here to read the translation.

Tagore’s long poem, Dushomoy (translated as Journey of Hope though literally the poem means bad times). Click here to read the poem in English and listen to Tagore’s voice recite his poem in Bengali. We also have a sample of the page of his diary where he first wrote the poem as ‘Swarga Pathhe'(On the Path to Heaven).

Deliverance by Tagore: ‘Tran’ by Tagore, a prayer for awakening of the subjugated. Click here to read the translation.

Abhisar by Tagore: A story poem about a Buddhist monk by Rabindranath Tagore in Bengali. Click here to read the translation.

Amaar Nayano Bhulano Ele describes early autumn when the festival of Durga Puja is celebrated. Click here to read the translation from Bengali.

Morichika or Mirage by Tagore is an early poem of the maestro that asks the elites to infringe class divides and mingle. Click here to read the translation from Bengali.

Purano Sei Diner Kotha or ‘Can old days ever be forgot?’ based on Robert Burn’s poem, Auld Lang Syne. Click here to read the translation.

Aaji Shubhodine Pitaar Bhabone or On This Auspicious Day, a Brahmo Hymn. Click here to read the translation.

Raatri Eshe Jethay Meshe or Where the Night comes to Mingle , a song written in 1910. Click here to read the translation.

Anondodhara Bohichche Bhubone (The Universe reverberates with celestial ecstasy), a song …Click here to read the translation.

Ebar Phirao More (Take me Back) a poem… Click here to read the translation.

Lukochuri has been translated from Bengali as Hide and Seek. Click here to read the translation.

Taal Gaachh or The Palmyra Tree, a lilting light poem, has been translated from Bengali. Click here to read the translation.

Nobobarsha or New Rain, a poem describing the rain transports one to Tagore’s world. Click here to read the translation.

Hobe Joye has been translated as Song of Hope for that is exactly what it is in spirit. Click here to read.

Eshechhe Sarat, a poem describing autumn in Bengal, has been translated as Autumn. Click here to read the translation.

Aalo Amar Aalo is a paean to light and its impact on us. Click here to read the translation.

Tomar Shonkho Dhulay Porey (your conch lies in the dust), is an inspirational poem to shed apathy. Click here to read the translation.

Prothom Diner Shurjo (The Sun on the First day) is one of the last poems of Tagore. Click here to read the translation.

Banshi or Flute is an inspirational poem delving into the relationship with the divine muse. Click here to read the translation.

Somudro or Ocean has probably been written during Tagore’s travels. Click here to read the translation.

Borondala (Basket of Offerings) is a poem of ecstasy. Click here to read the translation.

Nobo Borsho or New Year, is a poem written on the Bengali New Year, urging people to rid themselves of past angst. Click here to read the translation.

Bhoy hote tobo is the first Birthday Song by Tagore, a poem written in 1899. Click here to read the translation.

Pran or Life, a poem that reflects the poets outlook on life. Click here to read the translation.

Megh or Cloud is a poem about clouds with spiritual undertones reflecting transience . Click here to read.

Proshno or Question with its poignant overtones continues relevant to this date. Click here to read.

Sharat or Autumn, describes Bengal in the season of sharat or early autumn. Click here to read.

Amra Bedhechhi Kasher Guchho (We have Tied Bunches of Kash) is a hymn to an autumnal goddess. Click here to read.

Tomar Kachhe Shanti Chabo Na (I Will Not Pray to You for Peace) is a song that inspires to survive the dark phases of life. Click here to read.

Tagore’s 1400 Saal (The Year 1993), was read in London in 1993, including Tagore’s own rather brief translation and had a response from Nazrul. Click here to read.

Prarthona or Prayer is a poem in which the poet seeks inner strength. Click here to read.

Tagore’s Dhoola Mandir or Temple of Dust is a poem that questions norms, even from the current times. Click here to read.

Phalgun or Spring describes spring in Bengal. Click here to read.

Pochishe Boisakh (25th of Baisakh) is a birthday poem Tagore wrote in 1922 and from he derived the lyrics of his last birthday song written in 1941. Click here to read.

Chhora or Rhymes , a poem describing the creative process, it was written in 1941. Click here to read.

Okale or Out of Sync gives a glimpse of how out of sync situations are also part of our flow. Click here to read.

Mrityu or Death dwells on Tagore’s ability to accept death as a reality. Click here to read.

Olosh Shomoy Dhara Beye (Time Flows at an Indolent Pace) reflects his perspective on history. Click here to read.

Suprobhat or Good Morning gives an unusual interpretation to morning. Click here to read.

Book Excerpts

Songs of Tagore: Seven songs translated by Aruna Chakravarti from a collection that started her on her litrary journey and also our Tagore translation section. Click here to read.

Songs from Bhanusingher Padabali: Translated by Radha Chakravarty: Two songs by Tagore written originally in Brajabuli, a literary language developed essentially for poetry, has been translated by Radha Chakravarty. Click here to read.