An interview with Amina Rahman, owner of Bookworm, Dhaka

In a world, where online bookshops and Amazon hold the sway, where people prefer soft copy to real books, some bookshops still persist and grow. There are of course many that have closed business or diversified. But what are these concerns that continue to show resistance to the onslaught of giant corporations and breed books for old fashioned readers? How do they thrive? To find answers, we talked to a well-known bookshop owner in Bangladesh.

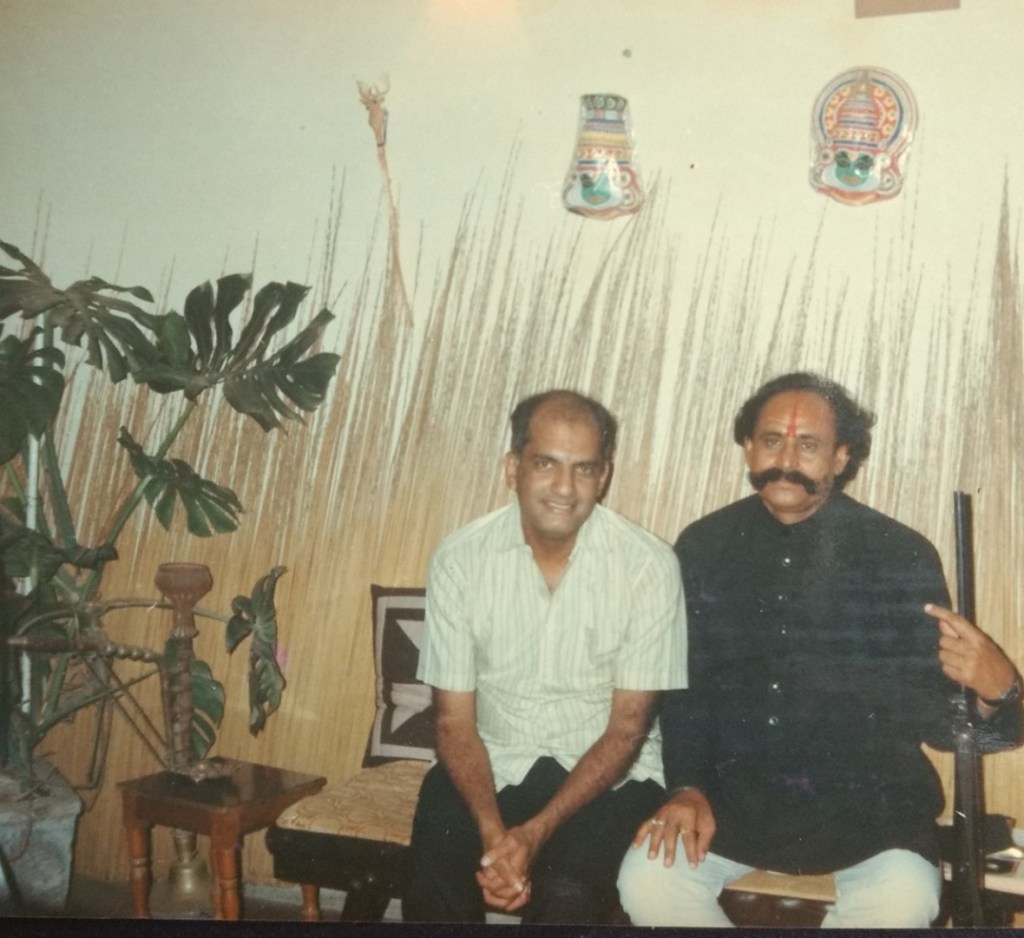

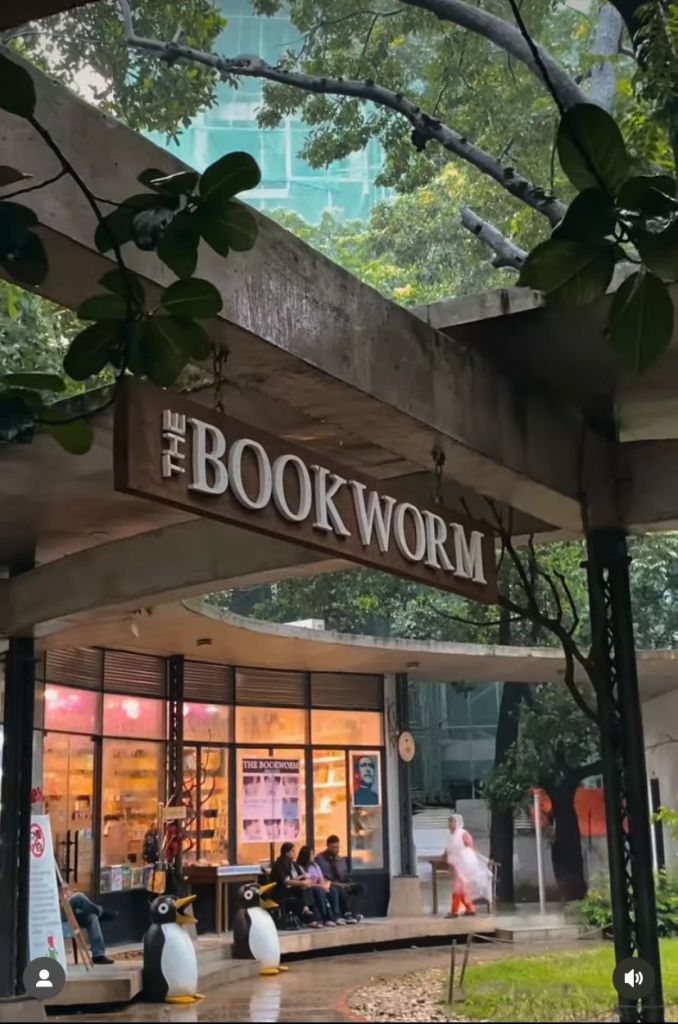

Amina Rahman is an entrepreneur who runs such a concern called Bookworm, a haven for book lovers in Dhaka. Schooled in Italy, India and America, Rahman married into the family that owned a small bookshop. Started by her father-in-law, it was a family refuge till she took over the running and created a larger community – a concept that she believed in and learnt much about during her youth spent on various continents. She believes that just as it takes a community to bring up a child, a bookshop has to be nurtured in a similar vein. Bookworm started at Dhaka’s old airport in 1994 and eventually moved to a more community friendly locale at the town centre. Rahman took over in 2012, rebranding it, repurposing and breathing new life into it.

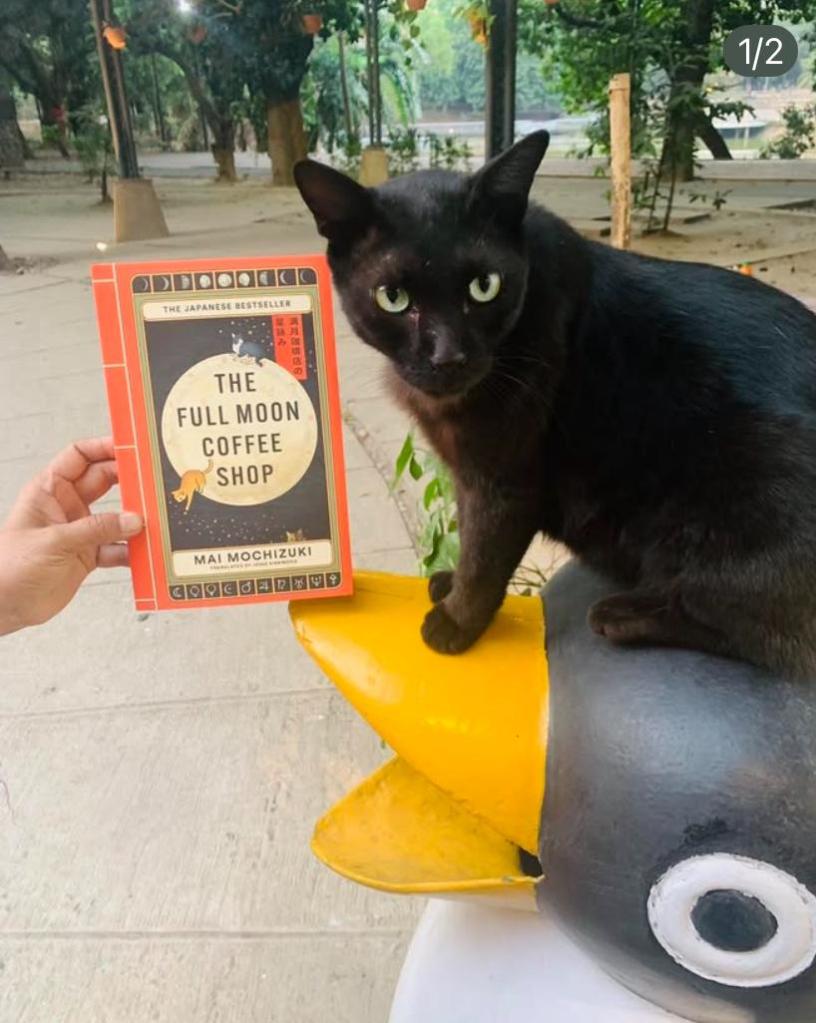

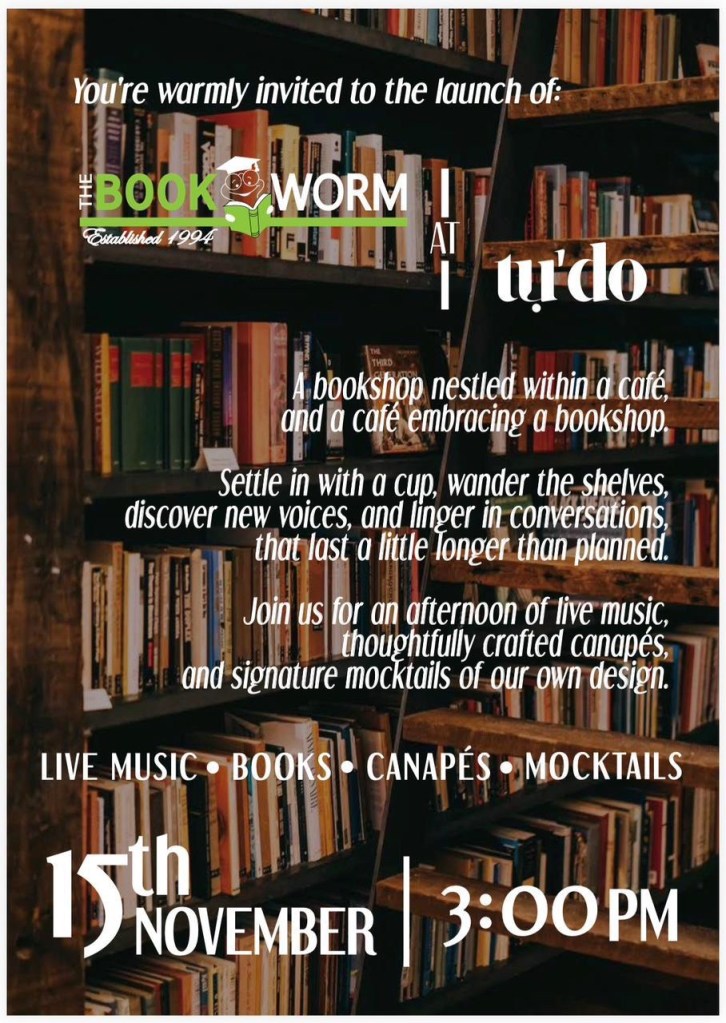

Bookworm houses books from all over the world, holds special launches, as they did recently of Sam Dalrymple’s Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia, and of many other local and foreign authors, like Vikram Seth and Aruna Chakravarti. They have even been adopted by the cats in the park! This month they are opening a book-café. Rahman has a unique outlook that makes her redefine ‘success’ and here she also talks about how she evolved into her dream project to make it a reality.

You studied environmental policy and environment, worked for several NGO’s and multinational concerns. What made you turn to or opt to run the bookstore over your own career options?

My choice of subject in university was impacted by a fantastic biology teacher I had in middle school at Rome. He took us out on regular field trips and made us collect garbage to learn about the environment! You can imagine — in 1984-85, when we were kids, he would pick up garbage and show us how diapers and cigarette butts were completely not biodegradable. Disgusting but effective. He told us it would take years before they deteriorated and dissolve into the Earth. These things stick in your mind.

To be honest, I followed the Environment path and ended up working for the King County solid-waste department in Seattle which was all about garbage and recycling and so fascinating. But as you get older and you travel through Asia, you realise the pointlessness of it all as none of it is applicable in the same way in our region. Bangladesh and Asia were green in those days until plastics were introduced in a big way about fifteen years ago. At the end of the day, the community is at the heart of taking care of everything, and if everyone takes care of their particular communities, it’s a better world. And this resonates with why I went into running the bookstore – to make community.

I realised that I was missing some kind of dynamism and I wanted to move forward. I wanted something more to happen. This had been a consistent strain I had with everything. You worked for organisations. They would become very top-heavy. Change happened slowly. When I shifted into the corporate world in Dhaka, I felt that was the most dynamic thing — it was fast moving. I learnt much. Then I went into market research, which was incredible research into human behaviour but was completely tuned into making money at whatever cost. It all was very self-serving and opposite of a welfarist approach towards the community. Corporations trumped community here.

I lost inspiration.

My father-in-law and I had a mutual love for books. I fell in love with my husband over his books. I married in 2004, and it was in 2012, when I was taking time out to assess my goals that my father-in-law suggested I spend time in his bookstore. So, I did. What was an amazing coincidence, was that the Dhaka LitFest started the same year! And the chief organiser asked if Bookworm could be part of the it and I agreed. Vikram Seth was the star guest that year.

Can you briefly tell us the story of Bookworm?

When I joined the Bookworm, it was almost a forgotten venture. The family had moved on to other interests. It was used more as a refuge for relatives, old staff, dusty books, unpaid debts and stalled time.

I had never run a business in my life before. For the book business I literally had to climb from the bottom up. It was definitely not easy. I had to figure out the book world, the suppliers, the publishers, the distribution network. Customer preferences, not to mention accounting, taxes, salaries and taking over a small business and the responsibilities that go with it.

The publishing world and the distributing world is a whole different ball game from every other business. It’s a supply chain of such remarkability from the packers and warehousing to the authors and customers. You go from the very basics to the highest and that is so fulfilling. Nothing can compare to that.

Besides, the love of books, one thing I knew was at bookstore was community. It is the ultimate community for booksellers and writers to connect with the world. As you will know, we hit every audience — everybody from the newborn baby to the old man or woman to young adults to school students to university goers to the erudite pursuing literature. We cover just about everything. Ultimately a physical bookstore is where the community meets, and that’s where the ideas are shared, that’s where if you put attention to it people meet inspiration.

While the Dhaka Literary Festival, in whose first iteration Bookworm was a participant, seems to have petered off, Bookworm continues to hold launches on its own. Do you see the shop as a substitute for the festival?

Absolutely not. I mean book launches are wonderful and are a must for every physical bookstore. They connect the people, and as I tell everyone, if you want to sell your book, even if you written the greatest book, you need to work hard at promoting the book. So, every writer needs to have venues whether small or big to launch their books.

Every city needs to have a LitFest, and it is a must. Dhaka is absolutely famous for having our Boimela[1]. That is a real heritage.

What is it you offer readers other than books? Do you have a café?

Actually, we are opening one now.

We didn’t have a cafe in the store, but we’ve had very interesting sort of cafe and bookstore combination when we were in the old airport. We had a cafe next-door to us, which I finally assimilated, also adding to more space for the books. And that became our own little cafe. It wasn’t really anything great; it was just regular we did not even have a coffee machine. Coffee was the old fashion Nescafe, but it did the trick. The whole set up had a very local flavour. Most of all people just like having an area to sit and drink something hot while freely reading books. And this sufficed.

That was wonderful. That store was in the old airport, which we loved with all our heart, and we were there for 30 years. Then we left. I opened up a branch in Dhanmundi, which is probably the best place for books sellers because the book reading population is huge there. We also got the opportunity to open up our bookstore inside a very famous Coffeehouse called Northend. They had a huge base, and they asked us if we’d like to take some of it and we did and that was fantastic.

We had to close that for Covid. Many say they miss it. And that was the first time we had ventured out of our space and opened a new store like a second branch. Then we got this chance to be in a park where we don’t have a cafe inside of our bookstore, but on the other side of the park, which is why we opened a café in our store.

What do you see as the future of bookstores like yours with the onset of online giants like Amazon? Does that impact you?

Yes. Amazon has had a huge impact. Luckily, we don’t have Amazon in Bangladesh. Amazon has had a very negative impact on our fellow booksellers in India and other places. I won’t even bother to compete with them.

I think everyone’s realised that there is a big difference with access points and how Amazon works. At the end of the day, people who come to our bookstore for the experience, for meeting other people, authors too, and talking to their bookseller. It’s more than just getting the book you want to read — that’s part of it — but it’s also about browsing and finding quiet time.

I think that my great experience with books was in bookstores I didn’t have to buy a book. I could browse. Sometimes, you may not be able to afford the book, but you can open it on any page. You could just read a passage, and that might change you. You could come back and buy it or the passage could just stay with you forever. You know it’s those sort of fleeting moments that you have when you’re browsing a book that makes a bookstore precious. That’s a very different experience from Amazon.

Amazon is much more utilitarian. Both have their ups and downs, I guess. You can’t have book launches on Amazon, but I think, Amazon is a big competition… in the sense that it also gives so many discounts.

What kind of books does your store offer? What kind of writers?

I tried to offer everything. In the beginning when we started, I started to try to figure out what books to get. I started with the catalogues, and it was a bit of hit and miss. You slowly start to realise what works. One of the worst experiences for bookstore are books that sit on shelves and don’t move. Sometimes you can buy what is really number one on the best seller list and it just doesn’t move because it’s irrelevant or it’s number one in a different country. You learn by trial and error and then you start to figure out your customers. It was painstaking yet enjoyable.

We use social media to draw readers to our shelves.

As a wholesome bookstore, we have a bit of everything from literature to history, kids’ books, romance, young adult fictions, thrillers, bestselling thrillers, to fantasy. Christie, Sydey Sheldon, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Manga, graphic novels, spiritual and religious books to Bangla books and collector’s items, special editions to lighter books that just bring solace. We see your customer choices and learn. You do not stuff literature down their throats. It has to be relevant to our customers.

What are the challenges of running a bookstore like yours in a country where English is not the first language?

I think actually it’s a challenge to run a bookstore anywhere in, especially with the new market forces of Amazon and online shopping and the digital world. Having physical stores is becoming a challenge. I have travelled to bookstores all over the world and learnt from the experience. A bookstore is more of a tactile experience for all people, readers and non-readers. Humanity has learnt from tactile experiences and to touch and smell a book, browse and sit amidst books is very much that. When realised that people were not coming to me, I took the books to them. I took our books to every mela(fairs). Social media was the next big thing. The ultimate was of course the Dhaka LitFest. People were excited to see our English books, and they all sold. Bangladeshis would travel to other countries to buy books as Bengalis love reading.

The LitFest helped a lot. It brought big authors, like Vikram Seth, for they were interested in exploring new readers.

We also started a delivery service. Some customers said it was hard to get to our store. So, we started a thrice week delivery service and then increased it. We bought a cycle for the rider. He went out and delivered the books that readers had ordered and paid for.

When Covid hit, it was prime time for many to turned to books and we had everything in place – our social media and our delivery service. We did well during that phase, though that is not a good thing to say.

What do you see as the future for your bookstore? There are chains like Takashimaya, Times Books and others — which despite having shrunk, post online bookstores, maintain an international presence. Do you see yourself as a chain that will grow into an international presence?

I think a chain store goes beyond the community. It is a model for more profit-oriented sellers. I would rather have a community-based culture where all people are welcome and find something that draws them and gives them a sense of quiet.

A lot of people mistake success with earning huge profits and if that’s what you’re in for that’s fine too — that’s business but what I do isn’t that. I get fulfilment out of other things –- community health and happiness, and you know just interaction. I think one of the ways to make a very powerful long-lasting brand and business is trust and good service. There’s no substitute for hard work and passion. When you love something, you really put your mind to it. And that helps you keep your friends forever.

[1] Bookfair

(This online interview has been conducted over transcribed voice messages in What’sApp by Mitali Chakravarty. All the photographs have been provided by Amina Rahman.)

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International