Book Review by Somdatta Mandal

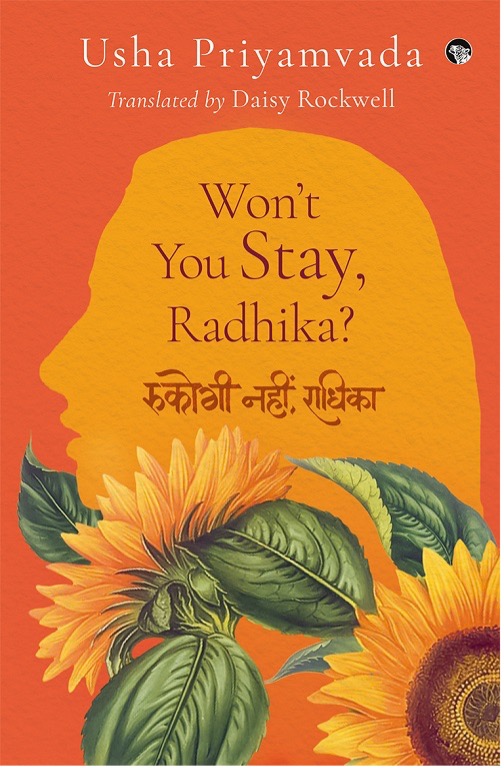

Title: Won’t You Stay, Radhika?

Author: Usha Priyamvada

Translator: Daisy Rockwell

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

In an essay written several years ago, the India-born Canadian author Uma Parameswaran had defined the plight of diasporic people by using the mythic metaphor of ‘Trishanku’ borrowed from the Ramayana where this character wanted to go to heaven alive but denied entry there, he was sent back and since then resided neither on earth nor in heaven but was suspended forever in an illusory middle space in-between. The state of diasporic individuals is somewhat similar; they are neither here nor there, and the present novel under review, published way back in 1967, brings out the angst of one such individual who, like the author Usha Priyamvada, herself went for higher studies to the United States and became the usual victim of culture shock. The only difference is that in real life Priyamvada stayed back in America and spent her long teaching career in universities there, whereas the protagonist of her novel Won’t You Stay, Radhika? went there only for a couple of years.

The storyline of the novel, originally written in Hindi, is rather simple. After her widowed father marries a younger woman called Vidya, Radhika’s world falls apart. She feels betrayed—the emotional and intellectual bond that she had forged with her father since the early death of her mother breaks with that sudden marriage. This is because their bond was not just emotional, but intellectual, as Radhika helped her father with his art history writing. To escape the unbearable situation at home—the growing rift between her and her father—Radhika fought for her personal freedom. Finding a simple way to avenge her father, she moved to Chicago along with an American teacher called Dan to pursue her master’s in fine arts. By leaving her father and going to live with Dan, Radhika had acquired several years of experience and matured quickly. But her living with Dan had only been a means to an end.

She returned to India two years later, burdened by a sense of alienation and homesickness, only to realise that while nothing had changed in her country, everything had. A growing sense of despair engulfed her. She started wondering whether she had a home anywhere. The family that she had longed to be reunited with barely acknowledged her arrival. The sense of belonging was missing, leaving her in ‘an emotional state of in-between-ness, of universal unbelonging’. As days pass, Radhika is paralysed with ennui, which is not just boredom. She avoids people, romance, family, as she lies still, or wanders listlessly through her neighbourhood. This sense of unbelonging tinges all her relationships—romantic or filial. So, she lies listlessly on her takht[1], bored, immobile, and uninspired.

This is not to say that Radhika is without love interests in the novel; after all there are three men in her life. She does not always feel detached from these men; there are many situations in the novel when we as readers feel that she has overcome her ambivalence or boredom or ennui, that she will start living a more meaningful life, but nothing positive takes place in the end. She seems to jell well with Akshay for a while and thinks probably she might marry him as there is no room in her life for a playboy. She wants a partner, someone steady, generous, someone who will accept her with all her flaws. But though she has great respect for him, she finally decides not to fall into the traditional trap of marriage. Akshay, like a traditional Indian male, also cannot subconsciously stop thinking about Radhika’s past. He feels confused as the more he wants to steer clear of Radhika, the more he feels she looms over his life. He also keeps on thinking about her past affairs with other men.

The other gentleman with whom Radhika had developed a relationship was Manish, who was diametrically opposite in nature to Akshay. They knew each other for a long time in many different contexts. Manish had also desired her, but Radhika had kept him at a distance. After several indecisive moments, she openly turned down his marriage proposal too, stating that she didn’t want to get involved again. Though she felt warmed by Manish’s touch, she did not turn to look at him. But Manish decided to wait till such time she changed her mind and voluntarily went to him. This ambivalence continues till the end of the novel, which Priyamvada leaves rather open-ended.

Though the title of the novel refers to a particular scene in the end when Radhika goes to meet her father once again and he wants his daughter to stay with him like before, that question mark hovers over the entire work: What will you do Radhika? Will you get up off the takht? Will this ennui ever come to an end? She was surprised at how her emotions had become so dull that she felt very little at all.

An extraordinary chronicler of the inner lives of the urban Indian woman, Usha Priyamvada is a pioneering figure in modern Hindi literature. Won’t You Stay, Radhika? written so many years ago, expertly explores the stifling and narrow-minded social ideals that continue to trap so many Indian women in the complex web of individual freedom, and social and familial obligation. A sense of alienation is also famous not only as a hallmark of Hindi literature of the 1960s, where it is usually traced to urbanization and the breakdown of traditional family structures, but also finds representation in Indian English novels too. Here one is reminded of Anita Desai’s famous novel Cry, the Peacock, published in 1963, that also delves deep into human emotion by focusing on topics like existential depression, psychological discontent, and the fragility of sanity as expressed through the female protagonist Maya. Though the theme of incompatibility and lack of understanding in marital life is one of the main themes of Desai’s novel, one notices a similarity of dealing with trapped feminine psyche in both the novels. Of course, reading the story of Priyamvada so many decades later, it seems nothing has changed in the Indian context and the situation in which the characters find themselves is equally true even today.

Before concluding, one must specifically put in a word of appreciation for the translation as well as the translator. On the first impression one is surely bound to think whether an American writer is the appropriate choice for translating a novel in Hindi. Apart from holding a PhD in South Asian literature from the University of Chicago and writing her doctoral dissertation on the Hindi author Upendranath Ashk, Daisy Rockwell has over the years to her credit translations of several Hindi authors including Usha Priyamvada’s debut novel Fifty-five Pillars, Red Walls (2021). But what brought her into limelight was her translation of Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand (2018) which became the first novel translated from an Indian language to win the International Booker Prize in 2022. Thus, apart from bringing this poignant Hindi novel to a new set of readers fifty-five years later, Rockwell’s expertise in translation makes one feel that this is not translated text at all. Though not a mystery thriller, her narrative skill makes the novel a definite page-turner and one will surely be tempted to finish reading it as fast as possible.

.

[1] Bed

Somdatta Mandal, an academic critic and a translator, is a former Professor of English at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International