By Sunil Sharma

The December morning came with a shock.

Pa was not in his room. It was crisp morning and the air brittle in your numb figure. There were raindrops glistening on the windowpane and on the treetops and the telephone poles. The cold hit you hard and your exposed skin felt like a reptile was crawling on it. It was as if your insides were being sliced with a cold dagger.

A Russian landscape, almost, that is typical of a Chekhovian story!

Bright, yet dismal!

Or Hemingway. Maybe.

The tall eucalyptus trees rose majestically in the distance. A clump of white, slender-waisted eucalyptus, half-a-mile away, near the shallow strip of river, swaying in the wind.

The silvery face of the river threw off a white haze. A few mud houses stood here and there. Vegetable fields ran down to the river edge, all green and rich, in the brilliant sun.

This side of the house, it is urban sprawl. That side, at the back, the country. This, ugly. That one, enchanting. The house he was standing in stood on a rising ground, all three-storied, of red brick, part completed, part painted, dwarfing other one-roomed houses of the small colony, recently sprung up, like the twisted innards, in an area, where basic amenities are as foreign as hunger is to the rich.

He surveyed the illogically constructed and misshapen houses where dirty and ill-clad children, nose running and feet bare, were playing, in the dust and garbage, with great gusto and abandon.

This house could not house a gentle soul! The man who spent his hard earnings in turning this dream into reality!

But where would Pa go?

The room, as usual, was very clean. The bed was made, the sheets smooth, the pillows neatly laid, the quilts neatly piled up. The English papers were kept in a corner. The bed was not slept in, at least, by the looks of it. The bookcases were lined with books — majority on philosophy and language, criticism and fiction. In English.

The soul had deserted the room!

“The aim of literature, good literature, mind it my boy, is to give courage, moral courage, to give insights into the nature of reality, the world,” a faraway look so typical of such encounters, “the courage to come to terms with life. To sort out the mess… to straighten up the whole twisted-up thing-life. What religion could not do, good literature does. It tells you about persons, the world, time…. A good artist is the seer…. Mad for conventional society but sane for the followers. Van Gogh, for example, and his sunflowers…”

During such moments, Pa looked unearthly. A halo appeared behind his head, the face dark in the erupting blinding light, the voice coming from clouds. He belonged to a different realm.

Is Pa an angel in human form?

How articulate!

So calm!

Looking at someone invisible, having a dialogue with that force, a dialogue liberating!

Pa communes with the spirits!

“Yes”, says he, “the dead speak. Through the mist of centuries. They come to me in dreams.”

He, the listener, is mesmerized. He cannot figure out the why of it.

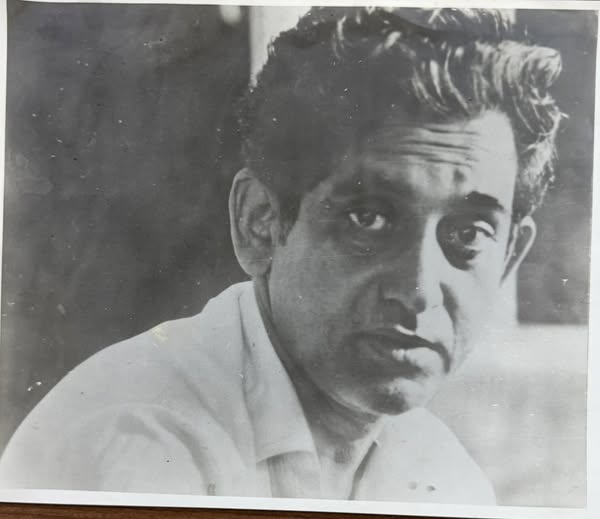

But he looks and listens. Pa is majestic. Regal. Tall, thin. Fine face.

A straight nose. Thin full lips. A pair of piercing brown eyes. A rich husky voice. An erect posture. Commanding attention. That is the sum total.

Pa.

“Cogito ergo sum. That is my philosophy.” Pa declared.

When he decides, he can be vocal. Very articulate. Precise.

Otherwise, he can be an iceberg.

Brooding. Off limits.

They had many animated discussions. Prod him on his favourite topic and he would be all animation. Gesturing. Eyes rolling. Hands moving up, down. Voice rising and falling.

“Nobody writes good literature. A soul companion in hours of solitude. Where are the Tolstoys, Romain Rollands, Hemingways, Nerudas in the 80s and 90s of the world? Human spirits speak through them. Now it is exhaustion. Personal idiosyncrasies. Language experiments”. He was dismissive. Hurt. Bitter. Literature had abdicated the messianic role. The artist celebrates a personal hell. What a climb down!

A reversal shocking. Market has ruined everybody.

Could Pa, this man of steel, desert us like this? Disappear?

He could not make any sense out of this sudden exit of Pa.

He returned to the room. It reflected the neatness of its occupant. A cold blast came from the narrow corridor adding to the silence of the room. Chilling! The wind ruffled up a stock of papers. The hissing sound unnerved him. He went out and down to the living room on the ground floor. The family was gathered up there. When he entered, they became quiet. He looked at them. They were lost in their own worlds. He thought he was intruding upon a private moment. He got up gingerly, without being obvious.

“Where are you going, Rajesh?”

It was Uttam, his eldest son.

“Just for a smoke,” he said.

“Any clue? Letter?” Uttam said without any conviction.

“No.”

“Where can Pa go?” asked Raman, the second son.

“Only God knows.” Uttam said dully.

Their wives and children stared blankly. Two more neighbours dropped in.

“What happened?” asked one old lady. “Nothing.” Uttam said with a note of finality.

“He ate his dinner. Watched the 10 P.M. news. Read a book till 11:30 pm and then retired,” said Raman, voice devoid of emotion.

“Very strange!” The lady exclaimed.

It was a quest for Rajesh now. He went to Amol Shrivastava. The retired man was alone in the flat, sipping tea and reading morning paper. He answered the bell on the third ring. They went out into the small balcony. The news surprised the old man.

“I met him yesterday,” said the old man. “He was cheerful. We went for our regular walk of three miles. He was pretty jovial. I cannot believe it.”

They were quiet for some time.

“I also cannot believe it,” Rajesh said. A healthy man suddenly disappeared without any clues. He was not depressed. Went for a morning walk. It was very confusing!

“When did they discover his absence?” Shrivastava asked, his lined forehead a furrow of crisscrossing lines.

“At about six. The youngest daughter-in-law went to his room with tea. He was not there. She left the tea there. An hour later, she returned. The cup was still there. Untouched.”

“Hmm!” grunted the retired accountant. “She raised the alarm,” Rajesh said. They had searched the house, the neighbourhood. Pa had left no trace.

“Maybe he went for a long walk!” Amol said, the voice drained of any feeling. “It is almost eleven now,” said Rajesh. “A man cannot walk that long!”

“Umm!” grunted Amol.

“A man cannot walk out like this, on a bitter winter morning, wearing a woolen sweater, a shawl, shoes, with little money and vanish just like that! It sounds ridiculous.”

‘Right.” agreed Amol. A man cannot!

‘Why did he do it then?” Rajesh asked.

“Was there any quarrel in the family?” Amol inquired.

“Not. as far as I know.”

“I cannot guess, either.” Amol said in a tired voice.

“Did he ever say anything about his family?” queried Rajesh.

“Never.” Amol answered. “He was very happy with his two sons, their wives. With his three daughters and their husbands. His wife, you know, expired ten years ago. He never complained.”

They fell quiet.

“I cannot figure it out,” Rajesh said, “a man suffering from nothing, apparently very happy, healthy, leaves his own house. And at the age of 63, to top it all. It is absurd!”

His next stop was the college. Some of his colleagues greeted the news with bewildered looks. A.N. Jha, a lecture in English, was unable to believe the fact.

“He is not that type!” exclaimed Jha. “He can never run away this way. I met him three days go in a literary function. We chatted for an hour. There was no sign of any stress or depression. And why should he? His sons were settled. Daughters married. He led an active life. He retired as a lecture in English. He was well known in the town. A great scholar. And a fighter. I mean I cannot believe it at all!”

“Jha Saab is right,” Trivedi from the department of Psychology spoke. “He was a healthy person. Social and outgoing. Affectionate. A hard worker. He can never do such a thing!”

Others also joined in.

The Pa that emerged from this group discussion was the Pa he had admired: strong, heady, realistic, with deep convictions, widely read, honest. A great intellect who was largely ignored in media and university circles of Delhi because of his roots in a small town that was a satellite of a hot, buzzing Delhi with its palace intrigues.

Apart from two books, he never published anything in a long and beautiful academic year. Since these two books were on Marxism, very scholarly and difficult for the pseudo, the Left also was miserly in its recognition of a small-town intellectual. Most of the Left travelled in cars, lived in big houses in south Delhi, worked in the university and had their books published by major publishing houses and went to London, Paris or Moscow. The town was still painfully feudal and backward where goons and the police and the rich ruled, where casteism, in the year 1999, was deeply entrenched in the social consciousness, despite the arrival of pizza huts, MacDonalds, Hondas.

Pa worked against all this with workers and peasants — worked for a dream in a world without Berlin Wall, U.S.S.R., for a unipolar world without boundaries; a world where a young student no longer read Capital but invested his small capital in an Archie card and gave it as a valentine to a demure lower-middle-class girl in the college corridors. In this world eating spring rolls or burgers and drinking Pepsi was more ‘happening thing’ than taking part in the student protests. Where the only ideology was myself and my world. “The whole world is getting Americanised. Third world, too quickly, I am afraid. The MacDonald culture is everywhere. The Walt Disney culture. The dollar culture. American businessmen should be congratulated. They have made all of us Yankees, without any force or coercion. We are Yankee with our brown, black and yellow skins. Is it not marvellous? Ha, Ha, Ha!”

Pa had laughed loudly in a wayside eatery, over cups of sugary tea, surrounded by a group of gaping followers and former and current students. A happy, star-struck group of lower middle-class young men, idealism running like a molten lava in their veins, dreams of conquering Everest, talking Brecht and Howard Fast and Miller, in that steamy, thatched, mud-plastered, small eatery near the highway, on charpoys, under the swaying eucalyptus trees, on a pleasant March evening when early spring was in the air and flowers were blooming and the scented air and the orange disk setting in the western sky lent an ethereal touch to the whole encounter there. Some of them were M.A. students and some, recent post-graduates in English, were unemployed. Majority wrote stories or poems or acted in plays. They wanted to be either famous authors or actors. They lived in a realm of young imagination and pure ideas with an enduring appeal, universal and eternal. They wanted to be artists in a market-driven era, and, in a town where there were hundreds of hotels and restaurant and one, very small shop that sold magazines in Hindi and English and a couple of popular English novels! With no reading culture or very little theatre there, they dreamed, like Pa, dreams that looked impossible for those who were not part of the camp.

“It is like discussing Shakespeare with a whore!” exclaimed a detractor once. Pa was unfazed, unruffled.

All of us have our dreams, some black and white, some Eastman colour, that is the only difference! Pa had remarked, face deadpan.

Remember, guys, the dead never dream! Pa had fascinated him. A hypnotic effect. Whatever he uttered became new gospel for him and souls kindred. Souls that found themselves misunderstood in family, home, society. They thrived on ideas and hopes. They became members of the clan and the Pa was the grand patriarch, a Moses, who was to guide them through the Egyptian wilderness to the promised land. A small band of warriors assaulting the monumental stone walls of the town. He thought Pa was a Von Gogh, painting sunflowers in an ugly urban sprawl which did not have a single potted plant constricted uncrushed by urban squalor and poverty. Only the human spirit thought of sunflowers, open meadows, wheat fields — of freedom, equality, of liberating world of imagination with frothy seas and magic casements and aching hearts. Only a genius could do that.

And suddenly this man disappears!

“Socrates, Tolstoy and Lincoln have one thing in common: a nagging wife,” Pa said once, while taking a long evening walk amid a cascading landscape of mustard flowers and a setting sun that had set the heavens on fire in deep crimson. Bird songs were sonorously punctuated by a scented, tranquil, ethereal air. The humble cottages of a fast-vanishing hamlet, off the main highway and on the outskirts of the town, loomed like far off phantoms in the gathering dusk and the invigorating country air, now seriously endangered because of the rapid encroachment of the town.

“But”, he had paused and stood there for a minute, appearing as a solitary figure in that solitary place, out of breath, “All wives are nagging, my boy. Ha, ha, ha.” The deep laughter unsettled a stork and made it fly. He looked imposing and formidable there, framed by a dark sky, the gentle wind ruffling his hair. He was giant, touching the sky, tall and erect, powerful and mesmerising, amid those undulating fields of mustard.

He resumed walking. The trance was over. “Somewhere at same point, you feel lonely. Terribly lonely. A perfect stranger. Look at Tolstoy. Driven out of his own home. Suffering from pneumonia. Homeless. Old man. King Lear minus the kingdom. Or Marx. Broken by the death of wife and daughter. Terribly lonely and isolated figure. Or Van Gogh. Or Dostoevsky. The list is long and impressive. Masters creating beautiful worlds, blessed with noble souls, yet lonely at a basic human level, suffering pain and humiliation, rejection. Ordinary life is like that. The difference is the artist transforms all this through art and becomes immortal. The ordinary man dies with this pain unsung. He cannot even share this pain with anyone.” He stopped momentarily.

“The thing is, boy, life does not favour art. This age is not favourable to it. It destroys your nobility, soul, person at the altar of money, commerce, vulgarity. You were born with divinity and end up dying as an animal.” He resumed walking again in the gathering gloom, “This age belongs not to Rembrandt or Leonardo but to the stockbroker, to DiCaprio, to Mario Puzzo,” a long pause. Then, “Look at the greats. Joyce becoming blind. Virginia Wolf and Sylvia Plath and Hemingway, committing suicide. Their spirits shining through their monumental works. But the same spirit is caving in, after a long battering. Joyce died poor. O’ Neil and Mayakovski, again embittered. They could never belong to this inhospitable place and cracked up. The most beautiful children, sensitive, highly intelligent and gifted, superior imagination, language — all these beautiful and innocent children of life, totally wasted by a cruel mother!” His voice had cracked up and choked.

A mournful silence descended, and the darkness suddenly appeared as eerie and gloomy. Lights were twinkling in the mud houses and seen through mellow enveloping darkness, looked magical and sweetly assuring and beckoning. A fire in an open hearth danced merrily and lit up a small surrounding area with hovering shadows and the mysterious black beyond frequented by the nightly visitors — the unseen spirits of the forest. The whole thing was unreal.

Finally, they emerged from the dark curtain on to the highway. Ear shattering cacophony of motor sounds and harsh sodium vapour lights invaded these two minstrels of a lost song. They went to a nearby tea stall. Rickshaw pullers were sipping tea.

“The thing is,” Pa said in an even voice, “the fact catches up with you sooner or later. In a grim fight between the fine spirit and the fact it is the vulgar fact that triumphs.” The air was putrid, heavy with charcoal smoke and dust. The tea was served by an ill-clad urchin with a swollen eye and of indeterminate age. The boy listlessly stared at the duo and then shifted his stare at the highway. “Imagination does not offer a permanent sanctuary to the alienated spirit,” Pa said, gazing at the passing motors, the characteristic far-off look in his liquid eyes, voice resonating, “Fancy cannot cheat us long. Facticity returns to claim us back. More viciously. More grimly. We wage a war against the desertification. A losing war but worth fighting for.”

And then, “What can you write in a bustling Las Vegas? Or what New York can offer you except its dazzling skyline?” If the name of John Barth were to be added to these stray observations, he thought, critics would have already started quoting and anthologising them! That is what marketing can do. They can create icons out of anonymity, obscurity. He looked at pa in the mild darkness lit up by a lantern. “You are wonderful. A genius!”, he exclaimed, admiration oozing. Pa smiled. Said nothing. Finally, “These are your sentiments. For the world I am a retired teacher. No more than that. Anonymous. Ordinary like millions. My name does not sell.”

“But market success is not everything!”

“Yes, it is,” Pa replied, sipping tea, “without market success, in a market economy, you are nobody, howsoever brilliant you are! It is the way you market yourself, that counts. The way you sell yourself. Otherwise, you are a zero.”

“Then why did you not sell yourself?”

“Because I hated the whole process. I can never do that.”

“But you are a great for me, for all of us here.”

Pa looked at him and smiled. “This small recognition is enough for me. And, by the way, after death, all are equal…unto dust thou shalt return.” He winked at him.

Now, looking back at this conversation, he could sense something which he had missed out at that time. Pa was deeply troubled and was trying to communicate this through this pantheon of artists, in an oblique manner, to him the loneliness, anguish, anger of an old, retired person who had made the painful discovery: that he was now redundant to his family and society. How dumb of him to miss the larger picture! A fine example of breakdown of personal communication.

But why did Pa take recourse to such a play?

Why did he not tell the plain truth to an adoring disciple?

That he was adored by a small group of artists who made him feel wanted and the feeling of being superfluous in the family, maybe, this social contradiction he could not resolve meaningfully. He had seen it happen earlier with others also. In late fifties, many had felt useless, with no defined role to play. The kids had outgrown their fathers. Most of them had turned to religion and yoga. They suffered diabetes, elevated blood pressure, angina pin, ulcers, and what not. Their eyes were sunk, skin leathery, teeth caved in, eyesight failing. They went on creating fictions. Reinventing themselves. Deep down they waited for the curtain call. A date with their maker. Religion comforted; paltry pension brought some cheer, but the gloom did not lift. The fact remained. They were no longer wanted. Had no price. Were irrelevant in a fast-changing society.

The police inspector, huge and rude, looked at him with malevolent eyes. So, what, if an old man is missing? He bawled angrily, is he a king or P.M.?

“Our Saab does not care about big shots,” the fawning sub-inspector said in a mocking tone. “He is the PM. of this station.” The huge pot-bellied inspector smiled. The graying handlebar moustache moved up and down on a fat face of a hard drinker. His blood-shot eyes were menacing, teeth pan-stained, garlic on breath. He looked intimidating. “A trigger-happy bastard,” he thought, “who shoots first and then asks.”

“See, officer, we have been made to wait here for two hours and nobody has bothered to take down out complaint,” he said in a mild tone, controlling anger and revulsion.

The inspector turned his full gaze on the speaker. The cop eyes were hard and full of hatred of a common, powerless man.

“Oh!’ He exclaimed and laughed. He pressed a button. A hungry-looking constable burst in.

‘Idiot,” the inspector roared, “where were you? Do you not see we have the governor sir here with us?”

The constable was confused. The inspector laughed uproariously. Sub-inspector also added a few decibels to the racket. “Governor, ha, ha, ha.” Inspector was rocking.

“Now listen Mr. Inspector,” he spoke in a commanding voice. The laughter died down immediately.

“Yes, Excellency!” the inspector said, taking out his revolver and playing it.

“I am Ashok Suri, news editor, with the star TV,” he spoke, slowly, a snarl dilating nostril. “A very good friend of S.S.P. and D.M. very close to the governor. A man is missing. An old man to people like you, but a father to these sons, teacher to me, a precious person to all of us! He is not a figure. He is a man. Ex-president of teacher’ union. Active on many fronts of the communist party. Do you get me?”

The inspector underwent a dramatic change.

Suri got up, followed by the two sons. “And I am going straight to S.S.P.,” Suri said, eyes blazing. “See you there, Mr. Inspector, the doorway. Except a lot of trouble tomorrow. Dharnas (strikes) by teachers, students and communist party workers. Goodbye, Mr. Governor. I will be there to cover it for my T.V. channel!”

They exited in a hurry. The cops came out in a fast-forwarding motion. The trio was escorted back. Tea and biscuits were served. The F.I.R. was lodged promptly. Half-an-hour later, they came out of the station.

Uttam shook hands with Suri, “Ashok you were superb!”

“What if they had caught your lie?” asked Raman.

“Oh!” Suri said, “you know I am a very good actor.”

“I spoke to them in the only language they understand,” said Suri.

The night came early and silently. The lanes were deserted. Houses stood shivering in the cold. Suri looked out of the window. The fog was swirling about like a ballerina, painting everything with a white brush. Somewhere a street dog was weeping, adding to the macabre. He was feeling tired and sad, Shambu came and sat down in the opposite chair. He lit a cigarette and spoke in a musical voice. Pa had come to me last Sunday.

“Was it?” asked Suri.

“Yes.”

“Was he disturbed?”

“Nope, slightly distracted.”

“I see. Anything else?”

“Well, well…lemme think… it was Sunday afternoon, and it was pouring…”

Pa had come around three in the afternoon. The overcast grey skies were pouring rain that came battering the neighborhood in a furious manner. Pa stood in the doorway, dripping, the grey hair being whipped by the cruel blasts of wind. Shambuda lived three houses away and was a good friend. Shambu sprang to his feet and welcomed Pa with a towel.

“So, what brings Marx here?” Shambhu asked.

“To meet Beethoven,” said Pa.

That was the opening gambit. Pa was Marx to Shambhu and Shambhu, Beethoven to Pa.

“What would your majesty have? Tea? Rum?”

“No Thanks.”

“No problem.” Shambhu, known as Da, went and brought two pegs of rum. Some salted cashew nuts.

“This lousy weather…pouring…kills my mood …to the angry elements and to Majesty’s good health.”

They sipped the liquid.

“Good stuff!” Pa said. “Fires up an old guy.”

“And makes the world red and golden,” Da said.

The wind-driven rain came in a sudden gust and lashed the shuttered glass Windows. Families were huddled around T.V. sets. It was bleak place. Dark, rainy, cold, cheerless. Pa was silent. Da refilled the glasses.

“Shambhu?” Pa said.

“Yes, boss,” replied the fiftyish portly man.

“It is dismal. This bleeding rain, this winter.”

“No quarrelling with your judgment, boss!”

“Can I hear a song from you?”

Da looked at his senior friend.

“No problem. Music is my first love.”

Da called his youngest son. Harmonium and tabla were brought out. Da sang a folk song, his favourite, in a sweet voice, the voice of a music teacher and a classical singer, a voice that always drew admirers, like pins to a magnet, from all the corners of the town:

Where are you,

My beloved?

I miss you dear,

In this rain and

Scorching summer,

Come back,

Come back,

Before I die,

Pining for

Your

Beautiful

Hair.

The melody, the earthly song, the rain and the rum. When Da finished and came out of the trance, he saw Pa wiping his tears with his hanky. Music had washed the souls of the two solitary figures on that wind-swept Sunday afternoon.

“I also have a distinct memory of that Sunday,” said Ashok.

Ashok’s Narrative

The sky was overcast, dull grey — a wet early evening gloom spreading in the vast skies, a strong wind pregnant with pearl drops of rain buffeting town and country. The streets were deserted. Pa was there in the doorway, smelling of hard liquor, wet and dishevelled, umbrella dripping. But Pa was always a welcome guest.

“Let us go, Ashok,” Pa said. A simple order. I look my umbrella and we went out on wet, slippery, pebbly road. Trees were shedding rain drops as big as stones. Birds were shivering. We walked two kilometers and then came to an abandoned culvert across a deep drain.

Around us were long stretches of soggy plains and looming mills and chimneys. We sat down on the wet culvert. Pa was quiet.

“Perfect setting for a rum-soaked evening,” I said, “for paneer pakoras (cottage cheese fritters), fried green chilies and roasted grams…”

“And hard-boiled eggs,” Pa said and laughed, his lean body shaking.

“If life were such a royal banquet…”

We lit cigarettes and emitted rings. Pa took out a half-bottle, two plastic cups, disposable soda and a packet of fried black grams topped with onion rings, tomatoes sliced and chopped coriander leaves, from the shoulder bag of khadi.

“Your wish is fulfilled, master.” Pa said.

“No, you are master, my master.” I spoke.

We drank and ate the grams. Pa was silent but I was used to his mood and unpredictable ways.

“Why do you love me so much?” he asked

“Because life teaches me through you. A fine, noble, learned man…”

“Who bothers an’ le guy like me? Who bothers for learning? For a mental worker? They bother for money. Cars. Good houses…Not a writer, a teacher, no, they do not care.”

“It does not matter…to me.”

“You are different, Ashok.”

“You, too.”

“That is why…we interact. I see myself in you.”

We sipped the rum. Dark thickness thickened.

“Folks like us are unhappy. Get crucified. Marked. We cannot escape our lot.”

I clung on to each word. Epiphany, you know.

“Once, during my young days, I walked along with my pop along a country road, on a dark wintry night, for five kilometers, to reach our village home. The road never seemed to end.

Father told many stories to lessen my fright. Then he lifted me up and put me on his shoulders. He walked, carrying his nine- year-old on his heavy shoulders, telling wonderful tales, to relive monotony, to comfort me, to ease my fears. The fields were full of mischievous ghosts…the wind produced strange music.

Shadows threatened…lions roared.

We were two Red-Indians walking the forest in night, watched by the spirits. I forgot my terror and listened to his comforting voice…

He paused for long period.

“That image still haunts me…Two figures and an unending road…A dialogue in the wilderness. He was my father, so was safe. Nothing could harm me. Twelve years later I had to travel the same road, alone. I had missed my last bus. The country road was same. My fears came back…lions still roared in my ears. Ghosts whispered. Shadows danced about. I was awfully scared. Death lurked. I died every minute. The journey took ages…when I arrived home, safe, I realised I was missing my father. A father who had died many years ago…”

Pa looked pathetic. Bent. Gaunt.

Ranting. They stood up on the fringes.

Sympathetically. Boundaries collapsed.

The steel in Pa was cracking up.

“When your own family denies you, mocks you, it is time to bid goodbye. “Listen to the Bard:

“……The tempest in my mind,

Doth from my senses take all

Feeling else,

Save what beats there! Filial

Ingratitude!

…No, I will weep no more…”

The rain was pouring. Gently dark veil had obscured everything. Pa was looking across centuries where another old man was holding forth his own private audience…

Sitting now, in Da’s room, I came to realise the import of that last encounter on that rainy lovely night.

.

“I must leave now,” Ashok said suddenly.

“Why?” Asked da, alarmed.

“I am tired,” Ashok said.

“O.K.!” Da said. “Do you think he would come back?”

Ashok stood up and reflected.

“No,” he said. “He won’t.”

“What do you mean?” Da was surprised.

“Well, he said his goodbye, on last Sunday,” Ashok said.

He came out and bent a last look at Pa’s house.

Goodbye, teacher!

Tears were running down the solitary man’s face.

.

Sunil Sharma is an academic and writer with 23 books published—some solo and joint. Edits the online monthly journal Setu.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.