Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea.

Fern Hill by Dylan Thomas (1914-1953)

Perhaps when Dylan Thomas wrote these lines, he did not know how relevant they would sound in context of the world as it is with so many young dying in wars, more than seven decades after he passed on. No poet does. Neither did he. As the world observes Dylan Thomas Day today — the day his play, Under the Milkwood, was read on stage in New York a few months before he died in 1953 — we have a part humorous poem as tribute to the poet and his play by Stuart McFarlane and a tribute from our own Welsh poet, Rhys Hughes, describing a fey incident around Thomas in prose leading up to a poem.

May seems to be a month when we celebrate birthdays of many writers, Tagore, Nazrul and Ruskin Bond. Tagore’s birthday was in the early part of May in 1861 and we celebrated with a special edition on him. Bond, who turns a grand ninety this year, continues to dazzle his readers with fantastic writings from the hills, narratives which reflect the joie de vivre of existence, of compassion and of love for humanity and most importantly his own world view. His books have the rare quality of being infused with an incredible sense of humour and his unique ability to make fun of himself and laugh with all of us.

Nazrul, on the other hand, dreamt, hoped and wrote for an ideal world in the last century. The commonality among all these writers, seemingly so diverse in their outlooks and styles, is the affection they express for humanity. Celebrating the writings of Nazrul, we have one of his fiery speeches translated from Bengali by Radha Chakravarty and a review of her Selected Essays: Kazi Nazrul Islam by Somdatta Mandal. An essay from Niaz Zaman dwells on the feminist side of Nazrul while bringing in Begum Roquiah. Zaman has also shared translations of his poetry. Professor Fakrul Alam, who had earlier translated Nazrul’s iconic ‘Bidrohi or Rebel‘, has given us a beautiful rendition of his song ‘Projapoti or Butterfly’ in English. Also in translation, is a poem by Tagore on the process of writing poetry. Balochi poetry by Manzur Bismil on human nature has been rendered into English by Fazal Baloch and yet another poem from Korean to English by Ilwha Choi.

Reflecting on the concept of a paradise is poetry from Michael Burch. Issues like climate, women, humanity, mourning, aging and more have been addressed in poetry by Shamik Banerjee, Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Milan Mondal, Kirpal Singh, Craig Kirchner, George Freek, Michael Lee Johnson and many more. Hughes brings in a dollop of humour with his response to a signpost in verse. Irony is woven into our non-fiction section by Devraj Singh Kalsi’s musing on writers and assailants. Ravi Shankar explores his passion for computers in a light vein. Snigdha Agrawal gives us a poignant story about a young child from the less privileged classes in India. Suzanne Kamata writes to tell us about the environment friendly Green Day in Japan.

Ratnottama Sengupta this month converses with a dancer who tries to build bridges with the tinkling of her bells, Sohini Roychowdhury. Gita Viswanthan travels to Khiva in Uzbekistan, historically located on the Silk Route, with words and camera. An essay on Akbar Barakzai by Hazran Rahim Dad and another looking into literature around maladies by Satyarth Pandita add zest to our non-fiction section. Though these seem to be a heterogeneous collection of themes, they are all tied together with the underlying idea of creating links to build towards a better future.

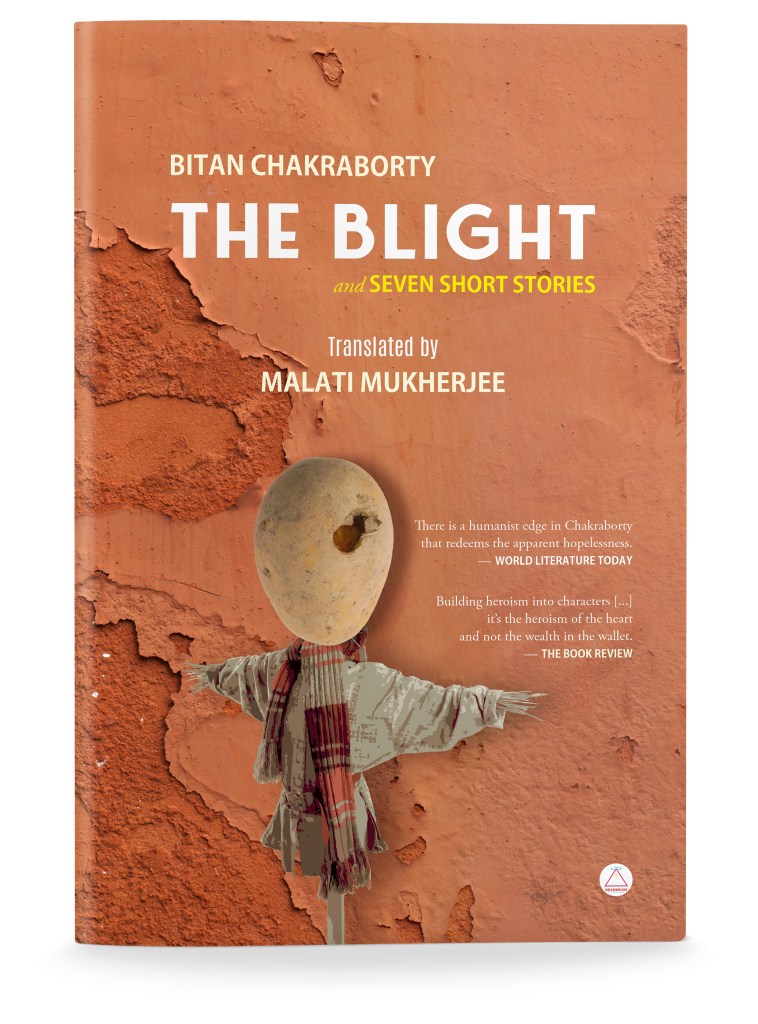

Our stories travel from Malaysia to France and India. Farouk Gulsara sets his in futuristic Malaysia, again exploring the theme of utopia as did his earlier musing. Paul Mirabile creates a story where a child tries to create his own idyllic paradise while Kalsi writes of fiction centring around a property tussle. The book reviews feature a couple of non-fiction. Other than Kazi Nazrul Islam’s essays, Bhaskar Parichha reviews Will Cockrell’s Everest, Inc. The Renegades and Rogues Who Built an Industry at the Top of the World. Ajanta Paul discusses Bitan Chakraborty’s The Blight and Seven Short Stories, translated from Bengali by Malati Mukherjee. Malashri Lal has written on Lakshmi Kannan’s Nadistuti: Poems, poems dedicated to Jayanta Mahapatra who the poet reflects lives on with his verses. And that is so true, considering this issue is full of poets who continue in our lives eternally because of their words. That is why perhaps, we recreate their lives as has Aruna Chakravarti in Jorasanko.

In focus this time is a writer whose prose is almost akin to poetry, Rajat Chaudhuri. A proponent of solarpunk, his novel, Spellcasters, takes us to fictitious cities modelled on Delhi and Kolkata. In his interview, Chaudhuri tells us: “The path to utopia is not necessarily through dystopia. We can start hoping and acting today before things get really bad. Which is the locus of the whole solarpunk movement with which I am closely associated as an editor and creator…”

On that note, I would like to end with a couple of lines from Nazrul, who reiterates how the old gives way to new in Proloyullash (The Frenzy of Destruction, translated by Alam): “Why fear destruction? / It’s the gateway to creation!” Will destruction be the turning point for creation of a new world? And should the destruction be of human constructs that hurt humanity (like wars and weapons) or of humanity and the planet Earth? As the solarpunk movement emphasises, we need to act to move towards a better world. And how would one act? Perhaps, by getting in touch with the best in themselves and using it to act for the betterment of humankind? These are all points to ponder… if you have any ideas that need a forum on such themes, do share with us.

We have more content which has not been woven into this piece for the sheer variety of themes they encompass. Do pause by our content’s page and browse on all our pieces.

With warm thanks to our wonderful team at Borderless — especially Sohana Manzoor for her fabulous art — I would like to express gratitude to all our contributors, without who we could not create this journal. We would also like to thank our readers for making it worth our while to write — for all of our words look to be read, savoured and mulled, and maybe, some will evolve into treasured wines.

Thank you all.

Mitali Chakravarty

Click here to access the content’s page for the May, 2024 Issue

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.